Heatwaves kill many more people in Australia than any other natural hazard, including bushfires, cyclones and floods.

Between 1900 and 2011 extreme heat was the cause of more than half of all deaths from natural hazards, apart from disease epidemics.

If global temperatures continue to rise as predicted, heatwaves will become more frequent, hotter and last longer.

Australian Government, State of Australian Cities, 2013:

Major heatwaves are Australia’s deadliest natural hazards, particularly for cities. Major heatwaves have caused more deaths since 1890 than bushfires, cyclones, earthquakes, floods and severe storms combined.

A hotter world

Australia is getting hotter along with the rest of the world.

Records collected by the Bureau of Meteorology show that Australia’s annually-averaged temperature has warmed by around one degree since 1910.

Over the last 60 years the nation has experienced fewer cold days, shifting rainfall patterns and more frequent hot weather.

The Bureau of Meteorology defines ‘hot days’ as those with a maximum temperature higher than 35°C. The intensity and frequency of heatwaves is related to climate change.

Measuring heat

The Bureau of Meteorology, established on 1 January 1908, is Australia’s national weather agency. Its records include regional weather data collected by the states during the 19th century.

The Bureau of Meteorology uses two methods to measure heat: via ground-based thermometers, located at around 700 automatic weather stations around the country which provide real-time information, and since 1979 in the atmosphere using satellites.

In addition to real-time monitoring of temperature, the Bureau of Meteorology also maintains a dataset containing more than 100 years of records from the Australian Climate Observations Reference Network – Surface Air Temperature (ACORN-SAT), which it uses to monitor climate variability and change.

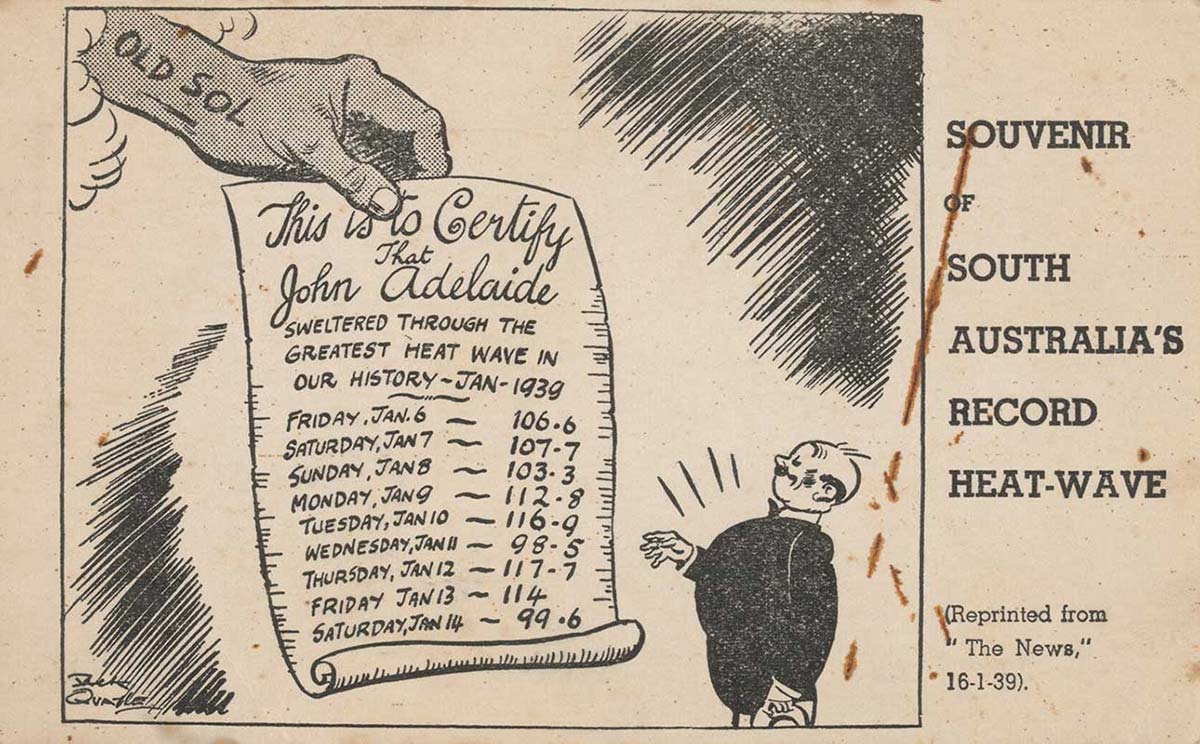

Australia moved from Fahrenheit to Celsius in September 1972, in accordance with the Metric Conversion Act of 1970.

Australia’s official temperature scale increased

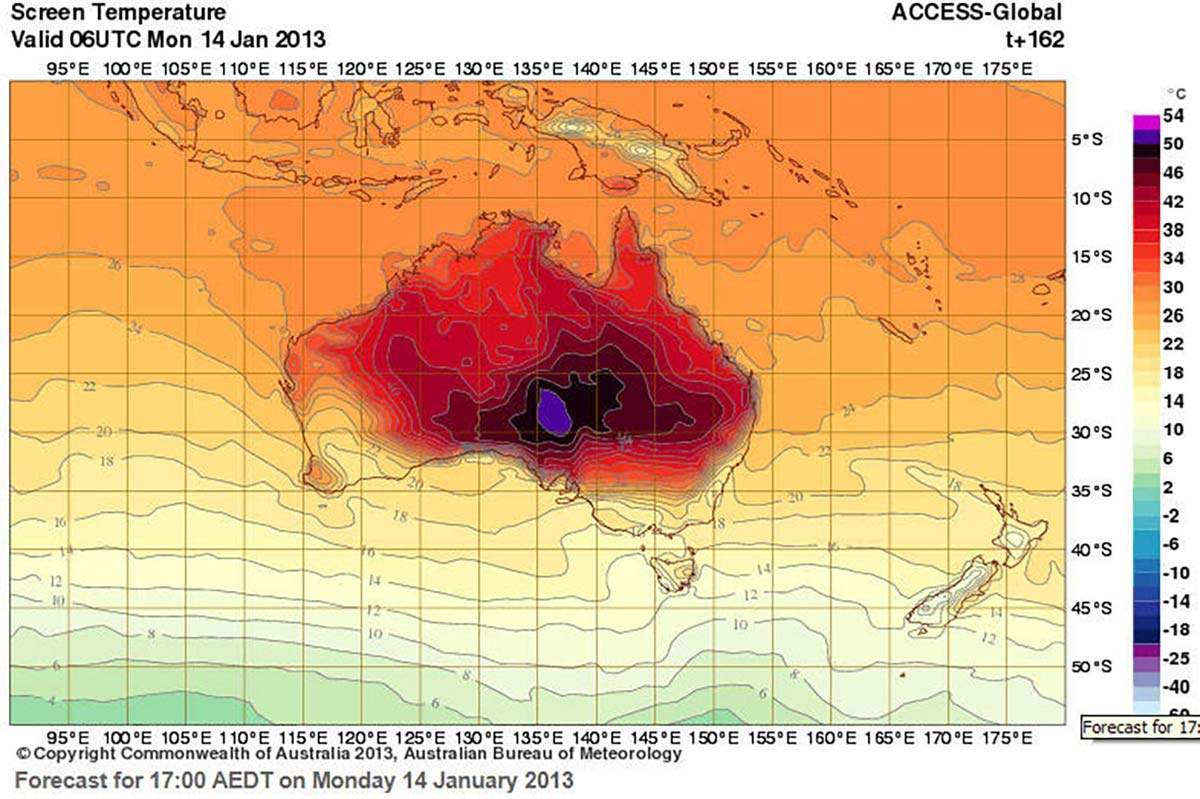

In January 2013 Australia was in the middle of a record-setting, two-week-long heatwave. On 7 January the average temperature across the whole continent was 40.3°C, and the Bureau of Meteorology forecast that the following day would bring maximums in excess of 50°C to areas which had already experienced temperatures in the high 40s for several days.

Up to this point, the maximum temperature shown on the Bureau’s heat map was 50°C, a temperature only exceeded twice since European settlement, when 50.7 was recorded at Oodnadatta, South Australia, on 2 January 1960, and 50.5 was reached at Mardie, Western Australia, on 19 February 1998.

On 8 January 2013 the Bureau of Meteorology added a new colour – dark purple – to the top of its heat scale to represent temperatures up to 54°C.

Since 2013 heat records continue to be broken, including in 2017 when many parts of the country experienced their warmest September day on record. Extreme heat is now a feature of the Australian climate and will continue to be so into the future.

What is a heatwave?

In 2014 the Bureau produced the first national definition of a ‘heatwave’: ‘three or more days where maximum and minimum temperatures are unusually high for a location’.

For example, temperatures constituting heatwave conditions in Tasmania may not be considered so in South Australia.

Heatwaves are classified as low intensity, severe and extreme. Most people can cope with low intensity heatwaves, but the next level, severe heatwaves, can result in significant health stress on vulnerable people, including the elderly and young children, pregnant women and people with chronic illness.

Extreme heatwaves (the highest category) are dangerous for all people if they do not take steps to stay cool. Such heatwaves can also adversely affect normally reliable infrastructure, such as power and transport.

Heatwave dangers

Unusually high overnight temperatures contribute significantly to making heatwaves dangerous. Hot nights prevent people, animals and the surrounding environment from discharging heat.

If the minimum temperature remains high then the following daytime heat will be higher, for a longer period, putting more stress on people’s ability to recover.

Heat stress occurs when the body absorbs more heat than it can get rid of. Heatwaves can cause deaths through heart attack, stroke and heat exhaustion or heat stroke.

Abnormally high temperatures expose natural and man-made systems to levels of heat with which they are not designed to cope.

Heatwaves cause significant crop losses and endanger livestock, pets and wildlife. Effects on infrastructure can include buckling train tracks and electricity blackouts caused by increased demand for air conditioning.

Heatwaves result in a surge in the number of people suffering heat-related illness, which puts pressure on hospitals and emergency services if they are not prepared.

An additional factor in the heatwave risk to humans and the environment is the common presence of high winds during these conditions. These can drive bushfires, such as the devastating outbreaks of 1939, 1983 and 2009.

Responses to heatwaves

In 2014 the Bureau of Meteorology launched a Heatwave Service, which it runs each year from the beginning of November to the end of March. The service gives up to four days’ warning of a forecast heatwave.

Victoria was the first state to develop a heat alert system in 2009, but since then most state governments have developed heatwave plans aimed at minimising harm to their communities and infrastructure.

Historical heatwaves

Since European settlement, there have been 11 heatwaves which resulted in significant loss of life. Some of these coincided with severe droughts, such as the Federation Drought (1895–1903), the Second World War Drought (1939–45) and the Millennium Drought (2001–09).

The most catastrophic heatwave, which was responsible for the death of 435 people, occurred between 1895 and 1896 and covered most of the country. In 2009, 432 people lost their lives during a heatwave in Victoria and South Australia.

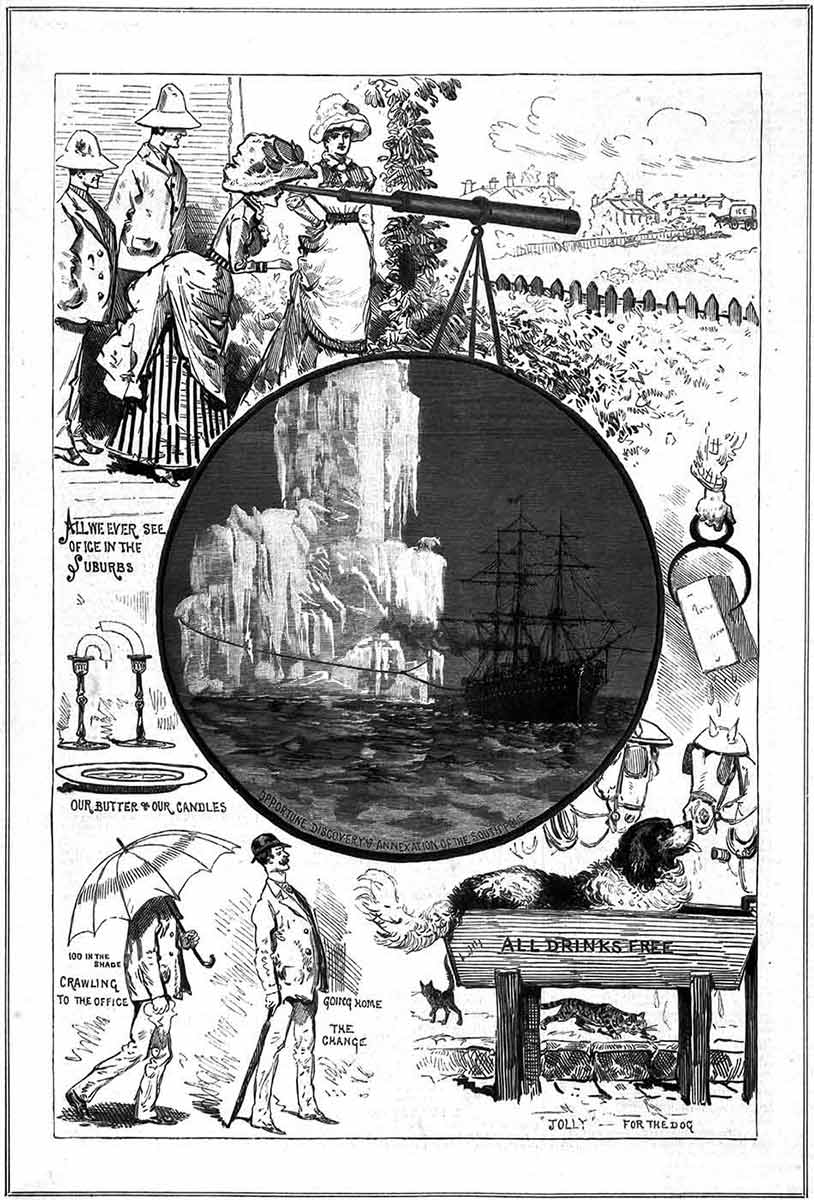

Before residential air conditioning became widespread, people coped with the heat by sleeping outside and swimming in public baths, the sea and rivers.

In the home, Australians devised ways of employing the cooling effect of evaporation, such as wrapping children in damp blankets and using a Coolgardie safe to store food.

The Geelong Advertiser, 23 December 1927:

The continuation of the heat wave has brought about a serious scale of affairs at the Perth Children’s Hospital … The hospital authorities are endeavouring to cope with the situation by constructing sleeping apartments inside hessian walls, saturated with water from pierced water-pipes running along the top of the walls … the babies’ ward is full of seriously ill babies.

Explore defining moments

References

Lucinda Coates and Katharine Haynes et al., ‘Exploring 167 years of Vulnerability: An Examination of Extreme Heat Events in Australia’, Environmental Science and Policy, vol. 42, October 2014, pp. 33–44.

Elizabeth G Hanna and Peter W Tait, 'Limitations to Thermoregulation and Acclimatization Challenge Human Adaptation to Global Warming', International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 12, July 2015, pp. 8034–8074.