British explorer Matthew Flinders was the first person to circumnavigate Australia. Flinders charted much previously unknown coastline, and the maps he produced were the first to accurately depict Australia as we now know it.

Flinders proved Australia was a single continent. By using the name ‘Australia’ in his maps and writings, he helped the word enter common usage.

Flinders in Voyage to Terra Australis, 1814:

Had I permitted myself any innovation upon the original term Terra Australis, it would have been to convert it into Australia; as being more agreeable to the ear, and as an assimilation to the names of the other great portions of the earth.

Flinders’ early career

Inspired by reading Robinson Crusoe, Matthew Flinders (1774–1814) joined the Navy as a midshipman in 1789 at the age of 15. He served on William Bligh’s second (and successful) voyage to Tahiti. It was here that Flinders honed the navigation skills that mark him as one of Britain’s most accomplished explorers.

In 1795 Flinders sailed to Sydney from where he made two short expeditions with the naval surgeon George Bass. The men, both in their early twenties, explored Botany Bay and the Georges River, and later Lake Illawarra. The boats they used for each of the expeditions were no more than three metres long.

Flinders also spent time on Norfolk Island and was sent to Cape Town to bring back livestock.

Van Diemen’s Land and Bass Strait

In 1798 Governor John Hunter gave Flinders, now a lieutenant, command of the sloop Norfolk and in this he and Bass circumnavigated Van Diemen’s Land, proving it to be an island. Flinders named the strait between the mainland and Van Diemen’s Land after his friend.

After exploring part of the Queensland coast, Flinders returned to England in 1800. The following year he published the findings of his expeditions, Observations on the Coasts of Van Diemen’s Land, on Bass’s Strait and its Islands, and on Part of the Coasts of New South Wales.

Circumnavigation of Australia

Flinders’ book won him some acclaim and he was able to persuade Sir Joseph Banks to support his proposal to explore the entire Australian coast.

Banks, who had great influence with the British Admiralty, backed Flinders because he was concerned that the French had designs on Australia. Banks knew that the explorer Nicolas Baudin was embarking on an expedition to explore the continent for Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Admiralty approved and financed the Flinders expedition. Promoted to commander, Flinders was given command of HMS Investigator in February 1801 and ordered to start his expedition by charting ‘the Unknown Coast’, namely the eastern part of the Great Australian Bight.

One of the purposes of the expedition was to establish whether New Holland (western Australia) and New South Wales (eastern Australia) were parts of the same continent.

Investigator

The Investigator was a collier, like James Cook’s vessels. She was eight metres wide and 33 long.

Her flat bottom made her suitable for exploration work, as she could navigate shallow waters and would remain upright if she ran aground.

Flinders arranged improvements for the Investigator, ensuring that more of her hull was copper-coated and that she was provided with additional boats.

Three months before sailing for Australia, Flinders married Ann Chappell whom he had hoped to take with him.

However, permission was refused and Ann stayed in England. Though the voyage was expected to take four years, the couple were not to see one another for nine.

Flinders sailed from England on 18 July 1801 and less than six months later arrived at Point Leeuwin – Australia’s south-western tip.

He headed east and arrived in Fowler Bay in South Australia on 28 January 1802. He then explored Kangaroo Island, the Spencer Gulf and Gulf St Vincent.

In April 1802 Flinders came across Baudin in what he named Encounter Bay where the Murray River empties into the Great Australian Bight.

Baudin was dismayed to find that Flinders had already mapped the nearby coastline. However, the meeting was cordial and Flinders told Baudin about food and water available on Kangaroo Island.

Flinders then set sail for Sydney, which he reached on 9 May 1802. Soon after, he again met Baudin, who had been forced to find refuge in the English colony because his crew were so debilitated by scurvy.

Flinders overhauled the Investigator and let his crew recuperate before heading north on 22 July 1802.

Encounters with Aboriginal men

Two Aboriginal men named Bungaree and Nanbaree accompanied him. Bungaree had the delicate task of negotiating with local tribes whenever Flinders wanted to go ashore.

Though Bungaree did not speak the languages of those he encountered, he did at least know many of the required cultural protocols and would have been of great value to the expedition.

Flinders carefully mapped the southern Queensland coast then passed through the Torres Strait into the Gulf of Carpentaria.

There it became clear that the half-rotten and badly leaking Investigator would not be able to make the return journey to England.

Reluctantly, Flinders decided to return to Sydney, continuing anti-clockwise around Australia. To do this quickly and safely meant he was unable to chart much of the western coast with the same rigour.

Maps for much of the west coast had been created by the Dutch in the 17th century.

Flinders arrived in the colony on 9 June 1803, nearly a year after leaving Port Jackson. Scurvy and dysentery had plagued the crew, and several had died of these and other causes.

But the journey had been a remarkable feat of navigation. It meant that Flinders, his crew and their two Aboriginal passengers were the first people to circumnavigate the entire continent.

Under arrest in Mauritius

In August 1803, keen to complete his surveying work of the Torres Strait in particular, Flinders set sail as a passenger on HMS Porpoise.

Unfortunately, the ship struck a reef off Queensland. Before the ship sank, everyone on board found refuge on a nearby island. Flinders navigated one of the ship’s boats 1127 kilometres back to Sydney where he arranged the rescue of the 94 other survivors.

The Governor of New South Wales, Philip Gidley King, complied with Admiralty orders by helping Flinders in every possible way. However, in his haste to return to England, Flinders accepted command of the schooner Cumberland, a very small vessel that proved barely seaworthy.

This forced him to seek help at Mauritius, which was then ruled by the French. Flinders arrived there on 17 December 1803, unaware that seven months earlier England and France had once again gone to war.

The French governor, General Charles de Caen, had earlier fought against the British. He and Flinders clashed and the relationship worsened due to Flinders’ tactless handling of the governor at their first meeting.

Flinders had a French passport, but it had been issued for the Investigator. Baudin had earlier written to de Caen suggesting he extend hospitality towards the English and Flinders in particular because of their friendly meeting at Encounter Bay and the help rendered him at Sydney.

However, De Caen ignored these requests and put Flinders under arrest. He held Flinders on Mauritius for six years, disregarding orders from Paris to set him free.

This might have been motivated in part by personal animosity but de Caen was concerned that Flinders was a spy, or that he would at least reveal to the British how poorly defended Mauritius was.

But Flinders had the freedom of the island and he put the time to good use, forming close friendships and working on his journals and papers.

It was only when the British fleet blockaded the island that de Caen released Flinders, in June 1810.

Final years

In October 1810 Flinders finally returned home to England and his wife, with whom he subsequently had a daughter.

While Flinders languished on Mauritius, the account of Baudin’s voyage had been published by the expedition’s zoologist, François Péron. Baudin himself had died on Mauritius shortly before Flinders had arrived there. Baudin’s expedition was an impressive achievement and certainly more scientifically fruitful than that of Flinders.

However, Péron assigned French names to features first named by Flinders to whom he gave no credit of discovery at all.

Now promoted to post captain, Flinders spent four years setting the record straight in his magnum opus, A Voyage to Terra Australis. But his health was failing, having developed a bladder condition that was probably the result of gonorrhoea he contracted in Tahiti 20 years before.

Flinders died at the age of 40 on 18 July 1814 – the day after his book was published. A copy was placed in his hands but he was already unconscious. He died without seeing it.

Mapping the continent

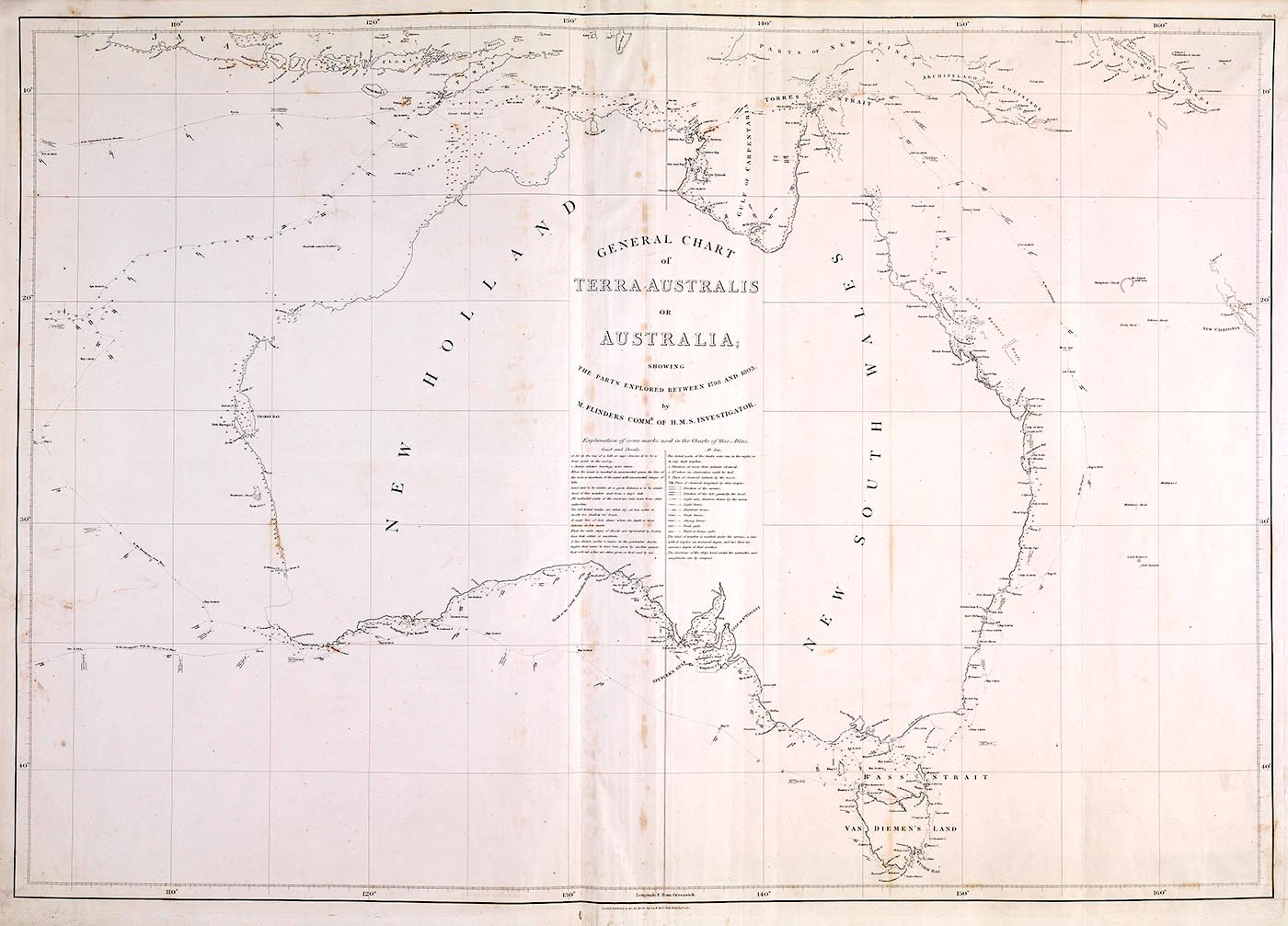

Flinders wrote to Sir Joseph Banks from Mauritius in 1804 enclosing his map of Australia. This map, and subsequent versions, were the first to present an accurate depiction of the continent.

Much of Australia’s coast had already been mapped, but Flinders came close to completing the picture. With great care and accuracy, he filled in enormous gaps, such as Bass Strait and the eastern part of the Great Australian Bight, and improved existing charts of Queensland and the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Most importantly he was able to show that Australia was a single continent.

He did this all in a ship that was barely seaworthy for much of the voyage, while enduring, along with his crew, a variety of privations and diseases over extended periods.

Naming the continent

Because the expedition proved that New South Wales in the east and New Holland in the west were the two halves of one landmass it was clear to Flinders that the continent needed a new name.

He labelled the map A chart of Terra Australis or Australia – Terra Australis meaning ‘southern land’, which was in common usage to describe the large southern landmass that was thought to ‘balance’ the great landmasses of the northern hemisphere.

The name ‘Australia’ had appeared in print before, again to describe the legendary southern landmass. The earliest printing of the name appears on a world map in a German astronomical treatise published in 1545.

The name appeared in English works 80 years later and was used occasionally after that, mostly in books. It is not clear whether Flinders knew of the word, or whether he coined it himself.

Banks did not support using ‘Australia’ and prevailed on Flinders to retain the Latin term, which he did in the title of his book. However, Flinders added the footnote quoted above, in which he indicates the term he preferred.

In 1817 Governor Macquarie received a copy of A Voyage to Terra Australis and used the term ‘Australia’ in his correspondence from then on. Britain formally named the continent Australia in 1824 and by the end of that decade it was in common usage.

In our collection

References

Encounter 1802–2002, State Library of South Australia

General chart of Terra Australis, National Library of Australia

Matthew Flinders, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Science in the colony, Exploration and Endeavour exhibition

Mapping our World: Terra Incognita to Australia, National Library of Australia, Canberra 2013.

Tim Flannery (ed), Terra Australis: Matthew Flinders’ Great Adventures in the Circumnavigation of Australia, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2000.

Geoffrey C Ingleton, Matthew Flinders, Navigator and Chartmaker, Genesis Publications, Guildford, UK, 1986.