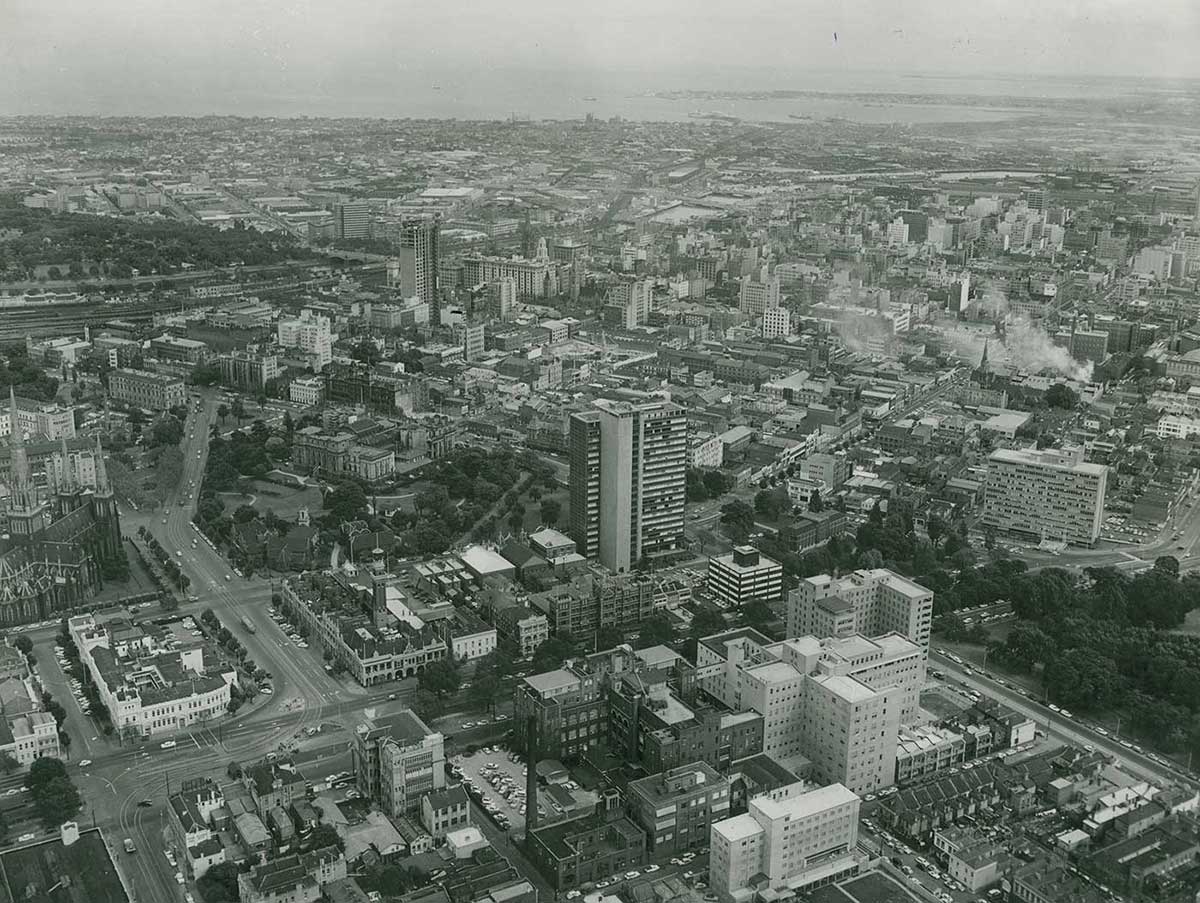

ICI House, now known as Orica House, was completed in 1958 by architectural firm Bates, Smart and McCutcheon.

It was the first building of the postwar era to exceed Melbourne’s rigid height restrictions. It paved the way for the gleaming contemporary look the city enjoys today.

Graeme Davison, City Dreamers, 2016:

In one bold leap, Melbourne threw off its Victorian dowdiness and became the most self-consciously modern Australian city.

Building height restrictions in Victoria

In the 1910s the height restriction for buildings in Melbourne was set at 132 feet (40 metres). The height was determined by the height of fire ladders at the time.

The restriction was a result of public concern for health and safety after an eight-storey building in Sydney’s Central Business District caught fire in 1901, killing five people.

Early calls for change

Melbourne, like most cities, has experienced many building booms. One boom in the 1920s was driven by economic prosperity and population growth.

Marcus Barlow, an established architect responsible for the Manchester Unity Building and the Century Building in Melbourne’s CBD, saw the need for change. In 1925 he gave a lecture at the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects in which he called for a review of the building controls that were inhibiting the growth of Melbourne’s inner city.

Citing examples from New York City, Chicago and San Francisco, Barlow proclaimed:

It is still necessary to build cities, and the requirements of commerce render it imperative that our cities shall not be wasteful of space. Business ‘abhors a vacuum’.

However, Barlow failed to change Melbourne’s building codes, and it wasn't until almost three decades later that another architect would achieve this change.

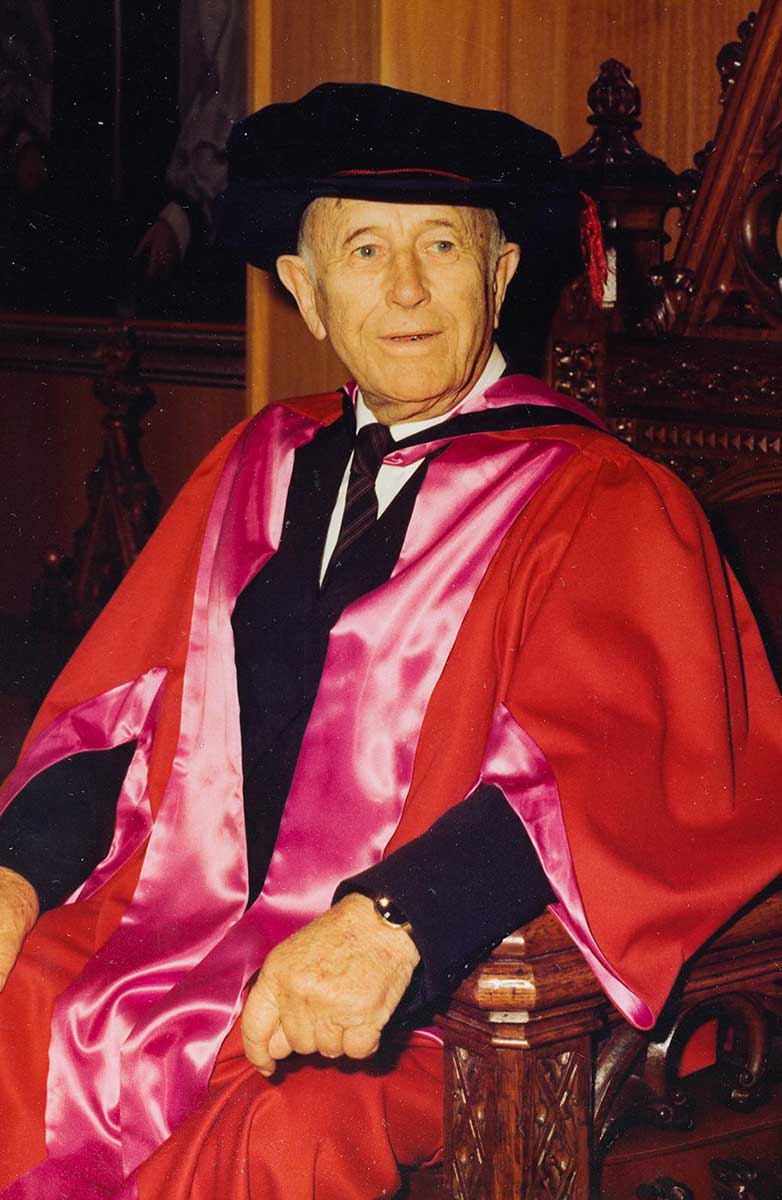

Architect Walter Osborn McCutcheon

Armadale-born Sir Walter Paul Osborn McCutcheon dedicated his working life to the Victorian architectural firm Bates, Smart and McCutcheon.

McCutcheon embodied a renewed focus on design quality. This was recognised by the award of the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects’ Victorian Street Architecture Medal on three occasions.

By the 1950s Bates, Smart and McCutcheon had become one of Australia’s largest and most successful architectural firms. It was known for McCutcheon’s concern for connecting architecture with other art forms, including sculpture and landscape design.

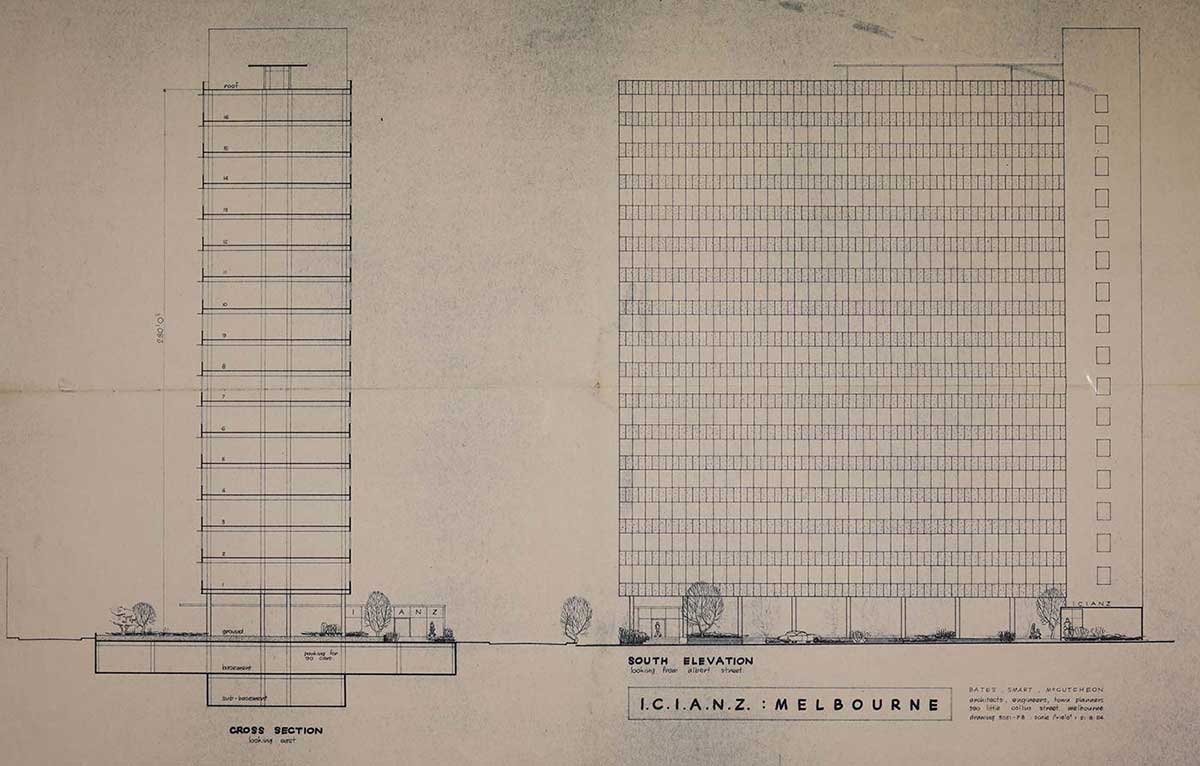

Under his direction, Bates, Smart and McCutcheon undertook to construct two buildings for Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI): one in Sydney in 1956 (since demolished) and another in Melbourne in 1958.

A rule-breaking deal

Plans for ICI House were approved on the basis that, in exchange for a height that exceeded set limits, the building would return certain public benefits. These would include public areas on the ground level and car parks that the public could use.

Giorgio Marfella from the University of Melbourne explained the fundamental elements of ICI House, including its public areas:

Office accommodation was in 17 levels served by eight lifts located in the side core. After completion, the top 12 floors were directly occupied by ICIANZ, with the remainder available for rent. The ground floor, surrounded by a landscaped entry, comprised a bank tenancy and a theatrette. The highest habitable level housed communal areas – a staff kitchen, canteen and cafeteria, as well as a caretaker’s flat. The basement housed a car park and part of the mechanical plant. The rest of the mechanical plant was located on a ‘penthouse’ set back from the parapet on top of the roof.

Among other innovations, ICI House exploited advances in local construction techniques, including framed glazed curtain walls and the use of concrete for flooring. It was an Australian take on international-style modernism.

Australian landmark

Construction began in 1955 and was completed in November 1958. It was officially opened on 11 December 1958. In his official speech, Sir Alexander Fleck, British chairman of ICI and President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, called it ‘an Australian landmark’.

The following week 20,000 people attended tours of the new office building. They marvelled at what was then the height of worker comfort, including a 400-seat cafeteria on the top floor that boasted unobstructed views across the city.

Until 1961 ICI House, at 84 metres, was the tallest building in Australia. It exceeded Victoria’s earlier building height restriction by almost 44 metres.

Legacy of ICI House construction

ICI House set new standards for building heights in Melbourne. It also set a precedent for negotiating special considerations in return for public amenities.

Not only did it represent changes in building regulations, but it also set new directions for high-rise office buildings that incorporated large open areas for staff to socialise in.

On 2 February 1998 ICI Australia launched ‘Orica’ as its new trading name. This led to the building’s name change from ICI House to Orica House.

ICI House was inscribed on the Australian National Heritage List on 21 September 2005. It was the first postwar office building to be added. This will ensure that its place in Australian and international architectural history is remembered.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Department of the Environment and Energy, ICI House

Heritage Council of Victoria, ICI House

Graeme Davison, City Dreamers: The Urban Imagination in Australia, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2016.

Giorgio Marfella, ‘ICI House and the birth of discretionary tall building control in Melbourne (1945–1965)’, Provenance, no. 16, 2018, pp. 19–32.