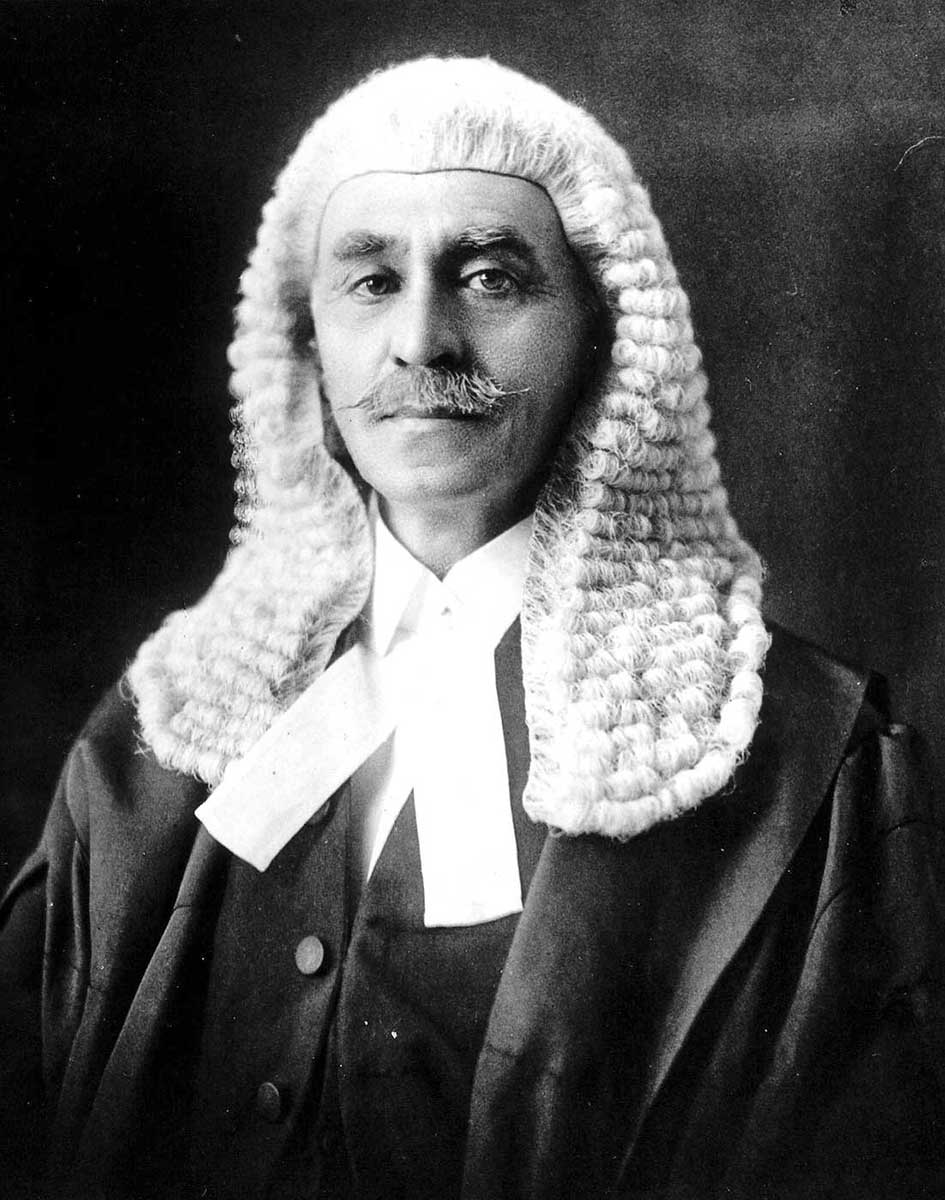

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs is best known for being our first Australian-born governor-general.

He was a strong defender of the British Empire and a patriotic Australian.

Isaacs proved that a ‘local man’ could hold the office as competently as the British aristocrats who had preceded him. But it was also as a politician, a High Court judge and a founding father of Federation that Isaacs made a lasting contribution to Australia.

The Hon Michael Kirby AC CMG, former High Court justice:

In difficult economic and political times, [Isaacs] helped Australia to steer a steady course. He thus upheld perfectly the particular magic of the peculiar system of government that is constitutional monarchy. He did so, despite George V’s fear … that a ‘local person’ … would be subject to the temptations of political engagement. It says a lot that such a deeply feeling, opinionated and powerful man was able to restrain his performance in the vice-regal office.

Australia’s governors-general

In the Australian system of government the governor-general acts in the British monarch’s name as head of state by facilitating the work of parliament and protecting the constitution. For instance, every bill passed by parliament has to be given royal assent by the governor-general before it can become law.

In addition, they have certain ‘reserve’ powers that include the right to dismiss the prime minister (such as happened with the Whitlam government in 1975) or dissolve parliament. The governor-general also plays an important ceremonial role.

As of early 2019, there have been 26 governors-general, of whom 13 have been Australian. Most of the 16 British-born governors-general were aristocrats with minor political backgrounds. Australian governors-general have tended to be pre-eminent men (and one woman) – usually former judges, politicians or generals.

Isaac Isaacs

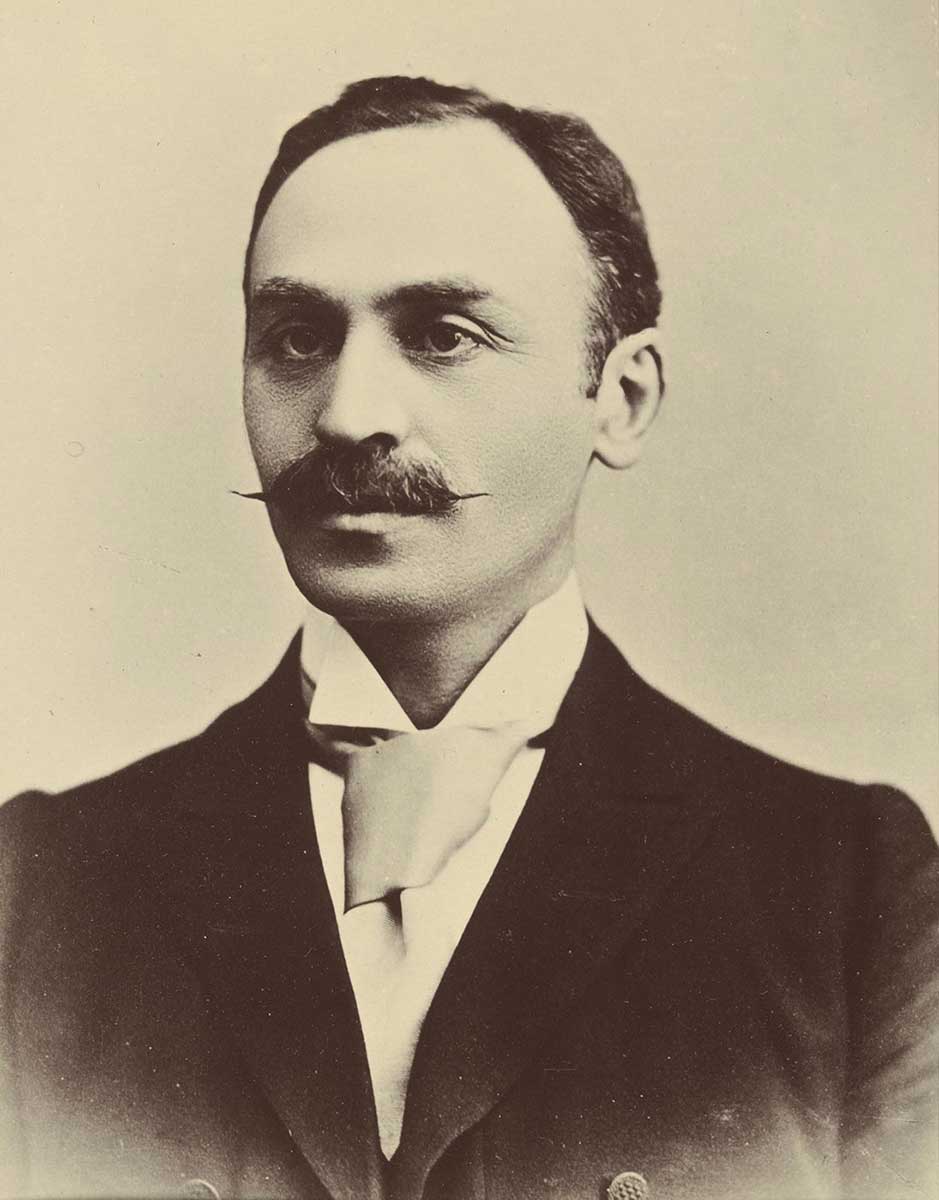

Isaacs was born in Melbourne in 1855, a year after his parents emigrated from Britain. His father was a tailor born in Russian Poland, while his highly intelligent and domineering mother was British. Both were Jewish.

Isaacs was a brilliant student at school, and was a pupil-teacher from age 15 until he was 20. He then found a position in the Crown Law Department in Melbourne and began studying law part-time at the University of Melbourne, graduating in April 1880 with first-class honours.

Two years later, he became a barrister and over the next 10 years built a successful practice despite a lack of money and connections.

Politics

In 1892 Isaacs successfully ran for the Victorian parliament on a progressive platform. He served as attorney-general for nearly seven years while keeping his law practice going. He became a Queen’s Counsel in 1899.

Alfred Deakin, Australia’s second prime minister, said of Isaacs during this period:

He was not liked or trusted in the House. His will was indomitable, his courage inexhaustible and his ambition immeasurable … Dogmatic by disposition, full of legal subtlety and the precise literalness and littleness of the rabbinical mind.

It was a view that reflected not only Isaacs’ personality and abilities, but also the anti-Semitism that prevailed at the time.

Federation

Isaacs was a keen advocate of Federation. In 1897 he was elected as a Victorian delegate to the second Australasian Federal Convention, though he was not elected to the constitutional drafting committee.

Following Federation, Isaacs turned down the opportunity to become premier of Victoria and won a seat in federal parliament.

Like many at the time, he was an ardent supporter of the White Australia policy while at the same time strongly in favour of women’s suffrage, the aged pension and fair conditions for workers.

He was appointed federal attorney-general in 1905, again while maintaining a thriving legal practice.

High Court of Australia

In October the following year, Isaacs was appointed to the High Court of Australia, where he remained for nearly 25 years. It was as a judge that Isaacs made his most lasting contribution to Australia.

He was acutely aware of the social and economic implications of his decisions, and when it came to constitutional issues his judgements reflected his commitment to national central power.

Isaacs received the first of three knighthoods in 1928. On 5 April 1930 he became Chief Justice of the High Court.

Appointing Isaacs as governor-general

Since 1887 Britain had held periodic Imperial Conferences with the prime ministers of its dominions.

At the 1926 conference it had been decided that the British Government would no longer make recommendations to the King about vice-regal appointments, but it had not been clarified who would do so in its stead.

In 1930 Governor-General Lord Stonehaven asked Labor Prime Minister James Scullin who he had in mind for a replacement.

Scullin came from an Irish Catholic working-class background, and he and his Cabinet decided they would recommend that an Australian fill the role. They considered former general John Monash, but he was too ill. Instead, they chose Isaacs.

When this became publicly known in Australia, the decision attracted strident criticism from conservative elements. It was thought that an Australian could not be politically impartial, and that an Australian as head of state would weaken the bonds of Empire. King George V felt the same way.

Scullin decided to wait for the 1930 Imperial Conference in November[1] before discussing the matter with the King. The conference determined that the dominion governments should make the recommendation, though only after informal consultation with the monarch.

Shortly afterwards, Scullin met with the King, who later wrote in his diary:

Received Mr. Scullin, and he told me he wished to appoint Sir Isaac Isaacs as the new Governor-General of Australia. He argued with me for some time – and with great reluctance I had to approve of the appointment. I should think it would be very unpopular in Australia.

He was wrong. It was controversial, but not universally opposed. Isaacs was sworn in on 22 January 1931.

Isaacs as governor-general

As with everything he had done in his life, Isaacs threw himself into the job. He travelled widely despite turning 80 while in office, and carefully examined all the legislation he gave royal assent to, sometimes sending it back for redrafting. He also thoroughly enjoyed the ceremonial aspects of his role.

Like many at the time, Isaacs held the paradoxical view that Australia was both an independent country and a stalwart member of the British Empire.

He was very keen to vindicate his appointment in the eyes of the King, and to show that an Australian could hold the post with the same degree of ceremony, gravitas and impartiality as a member of the British aristocracy.

This he did. The fact that he was the first governor-general to have an impeccable background as a legislator and jurist helped him fulfil his constitutional duties to the highest level.

Because of the Depression, Isaacs lived frugally at Government House in Yarralumla, forgoing a quarter of his salary, his High Court pension and his official residences in Sydney and Melbourne. He also took a keen interest in the early development of Canberra.

Isaacs retired on 23 January 1936. Though he had acquitted himself superbly, the conservative government under Joseph Lyons replaced him with a Briton, Sir Alexander Hore-Ruthven VC.

Legacy

Isaacs was one of Australia’s finest legal minds. It was an extraordinary feat that a man from a humble immigrant and Jewish background could have held two of the three most important offices in the land. He helped make Australia more than a collection of disparate states.

In the words of Victorian Supreme Court Justice Sir John Barry:

his efforts were directed towards the amelioration of social misery and the uplifting of mankind

Notes

[1] The conference was also significant in that it established legislative equality between the dominions and Britain.

You may also like

References

Role of the Governor-General, Commonwealth of Australia

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs, The Australian Dictionary of Biography

Zelman Cowen, Isaac Isaacs, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland, 1993.

Max Gordon, Sir Isaac Isaacs: A Life of Service, Heinemann, Melbourne, 1963.

Michael Kirby, ‘Isaac Isaacs: Driven, difficult, influential’, Victorian Bar News, vol. 154, Summer 2013, pp. 28–31.