Wheat was one of the first crops planted by colonists in 1788. Initial harvests were poor but soon the grain had become Australia’s most important crop.

However, with the appearance of black stem rust, a devastating wheat disease, harvests began to decrease in the second half of the 19th century.

William Farrer experimented in crossbreeding wheat to produce Federation wheat, the first specifically Australian variety that was both rust- and drought-resistant.

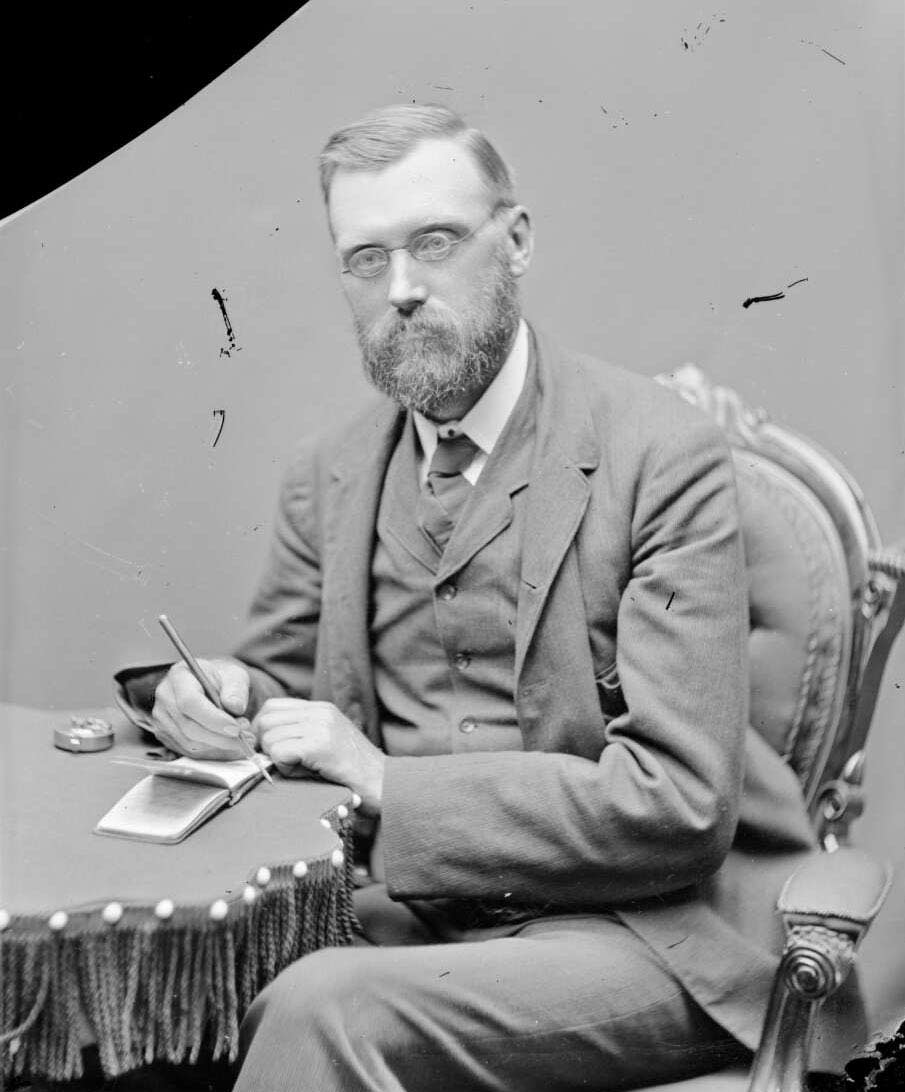

William Farrer, 1900:

In a new country like this, where the climate is so widely different and in many respects the very opposite of that of the country which, only a short time ago, was the home of the vast majority of our farmers … the traditional practices of the old country have to be unlearnt, in addition to entirely new ones learnt.

First Australian wheat

The first wheat in Australia was sown in Sydney in 1788 not long after the arrival of the First Fleet.

Colonists had brought different varieties of grain with them and a small nine-acre farm was established at Farm Cove on the site of the current Royal Botanic Garden to raise and experiment with various crops.

The climate, soils and seasons were so dissimilar to those of the wheat’s native land that the first harvests were very poor.

James Ruse, a convict, was one of the few experienced farmers sent out with the First Fleet. In July 1789 he claimed that he had served his seven-year sentence (as much of it had been spent on a hulk in England prior to transportation).

He asked Governor Arthur Phillip not only for his freedom but for a grant of land. In November, Phillip allowed Ruse to farm a smallholding near Parramatta.

With productive harvests over the next two years, Ruse proved that wheat could be a successful crop in the new colony. Phillip granted him title to the land he was farming, making Ruse the first emancipist (freed convict) to receive title to land in New South Wales (NSW).

Problems with wheat

With the opening up of new agricultural areas in Van Diemen’s Land, Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia and the continent’s interior, wheat became Australia’s primary crop and eventually an export commodity. The first shipments to England began in 1845, and by 1870 regular exports had begun.

However, black stem rust, a devastating wheat disease had appeared in Australia shortly after the first crops were harvested. Between 1840 and 1860 stem rust forced farmers to move farther inland to the drier, hotter interior. This environment was much less suitable for European-derived wheats and slowly grain productivity decreased.

In 1889 a severe rust epidemic cost the wheat industry £2–3000,000 in lost production. Grain millers in the colonies had to import wheat. Colonial governments recognised the need for coordinated action and from 1890 they established a series of annual, national conferences to address how best to fight the disease.

In the late 19th century, several farmers, agriculturalists and scientists began experimenting with wheat selection and breeding. Notable alongside William Farrer was agricultural educator Hugh Pye and farmer Richard Marshall. In Marshall’s case, it was his experience of losses to rust, that prompted him to import wheat from Europe and the US and develop rust resistant varieties, including the popular Marshall’s No. 3.

William Farrer

William Farrer was born in 1845 in Westmorland, northern England. He received a scholarship to Cambridge University and gained a Bachelor of Arts in 1868.

He began studying medicine but was unable to finish the degree after contracting tuberculosis. At the age of 25 he migrated to Australia believing the warmer, drier climate would be beneficial to his health.

Farrer started his life in Australia as a tutor at George Campbell’s sheep station, Duntroon, in what is now Canberra. He soon developed an interest in agricultural science and his first publication, Grass and Sheep Farming, a Paper Speculative and Suggestive, appeared in 1873.

Over time his focus shifted to the problems of wheat-growing in Australia. Farrer came to believe that the farmers’ difficulties were rooted in the unsuitability of European-derived wheats to the Australian climate.

Farrer had hoped to buy pastoral land, but the poor performance of his mining investments left him short of funds. He qualified as a surveyor and began work for the NSW Department of Lands in 1875.

Wheat experimenting

In the early 1880s Farrer began selecting seed from superior individual wheat specimens around the colonies and planting them in small, carefully delineated plots on his father-in-law’s property at Cuppacumbalong, NSW, near what is now Canberra.

He was aiming to find the most suitable species for the Australian climate and soon extended his experiments to include overseas varieties.

Farrer resigned from his surveying position in 1886 and bought Lambrigg Station close to Cuppacumbalong. There he began crossbreeding the different wheats he had identified.

These were some of the first plant hybridisation experiments in the world. Farrer cross-pollinated the plants using his wife’s hairpins to transfer the fine grains of pollen until he acquired a pair of forceps.

By planting the new seed in his experimental plots he could gauge the wheat’s success, select the strongest performers and then replant. In this systematic way he produced hundreds of crossbred plants.

Rust and experiments

The disastrous wheat crops of 1889 and 1890 brought Farrer’s work to the fore. He made annual visits to the national Rust in Wheat Conferences around the country to discuss his findings. Unlike his contemporaries, Farrer sought to produce a wheat that was not only rust-resistant, but whose grain could be milled and baked better.

In 1898, Farrer was appointed as wheat experimentalist with the NSW Department of Agriculture. He worked with the government chemist FB Guthrie who made available miniature flour-mills and bakehouses that could produce 50- to 100-gram samples.

Farrer could now mill and bake small quantities of many types of hybrid grain and select the strongest wheat, based on evidence rather than prejudice or reputation.

Development of Federation wheat

Farrer came to believe that Indian wheat, which escaped rust because of its early maturity, could be the basis of a more disease-resistant plant. Guthrie and Farrer’s experimentation on the commercial milling and baking of grains showed that the Canadian Fife wheat was the world leader. However, Fife matured later in the season, exposing it to a higher risk of disease.

The answer seemed to lie in the hybridisation of both. This led to the production of new strains such as Yandilla and Comeback.

However, millers still preferred the old softer grains from European-derived wheat. In 1896 there was another poor harvest and millers were forced to import hard North American wheats. Comparisons between the imported grain and Farrer’s rust-resistant crossbred types proved that the new strains could be commercially viable.

Farmers began to take up Farrer’s new wheats, but the breakthrough came when Farrer combined Yandilla with the European-derived, high-producing Purple Straw variety. This created a rust-resistant, high-yielding, strong straw plant. Farrer named it ‘Federation’ in honour of the creation of the Australian nation in 1901.

Distribution of Federation wheat began in 1903. The wheat industry quickly realised the plant’s potential and took up the variety. From 1910 to 1925, Federation was the most widely planted wheat in the country.

Farrer's legacy

Farrer’s experimentation created a variety of wheats suitable for different environmental conditions across the country and these new strains allowed vast new areas of the country to be opened up to grain production. In NSW alone, there was a four-fold increase in wheat grown between 1897 and 1915.

Farrer is also remembered as a pioneer in the field of plant genetics. His experiments at Lambrigg took place at the same time as scientists in Europe were rediscovering and applying Gregor Mendel’s work in this area.

Wheat has become Australia’s largest and most valuable crop. More than 50 percent of Australia’s cropped land is planted with wheat. In 2014–15, almost 30,000 farmers were responsible for growing over $7.1 billion worth of wheat, almost 15 per cent of the total value of Australia’s agricultural production.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

William Farrer, Australian Dictionary of Biography

'Experiment Farms,' The Chronicle (Adelaide, SA), 17 February 1900, p 42, on Trove

The Australian Wheat Industry, Australian Bureau of Statistics

Wheat breeder occupational category, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Archer Russell, William James Farrer, A Biography, FW Cheshire, Melbourne, 1949.