The Federation Drought from 1895 to 1903 was the worst in Australia’s history, if measured by the enormous stock losses it caused.

It ended squatter-dominated pastoralism in New South Wales and Queensland, as bank foreclosures and the resumption of leases led to the partition of large stations for more intensive settlement and agricultural use.

Dorothea Mackellar, ‘My Country’, 1908:

Core of my heart, my country!

Her pitiless blue sky,

When sick at heart, around us,

We see the cattle die –

But then the grey clouds gather,

And we can bless again

The drumming of the army,

The steady, soaking rain.

What is drought?

Australia is the driest inhabited continent, a place where periods of low rainfall lasting up to a decade or more are commonplace. The Bureau of Meteorology defines ‘drought’ as ‘a prolonged, abnormally dry period when the amount of available water is insufficient to meet our normal use’.

History of drought in Australia

Historical accounts and scientific analysis indicate that South-Eastern Australia experienced 27 drought years between 1788 and 1860, and at least 10 major droughts between 1860 and 2000.

The Millennium Drought (2001–09) was one of the most severe. In 2017 drought set in again across parts of New South Wales and Queensland.

The Federation Drought received its name because it coincided with Australia’s Federation. Many consider this drought, which affected almost the whole country, to have been the most destructive in Australian recorded history, owing to the enormous toll it took on sheep and cattle numbers.

Expansion of pastoralism before the drought

By the end of the 1840s an area of about 28 million hectares was occupied by fewer than 2,000 squatters on Crown land.

To control the squatters and encourage closer settlement, the eastern states introduced land reforms in the 1860s. The goal was to break up large runs into smaller blocks for farming and grazing. This was not always achieved as squatters found ways to hold on to productive country.

Nevertheless, many selectors took up ‘homestead’ blocks, in the Mallee region of North-Western Victoria in the 1870s and, in the Western Division of New South Wales (the western third of the state, comprising about 32.5 million hectares) from 1884.

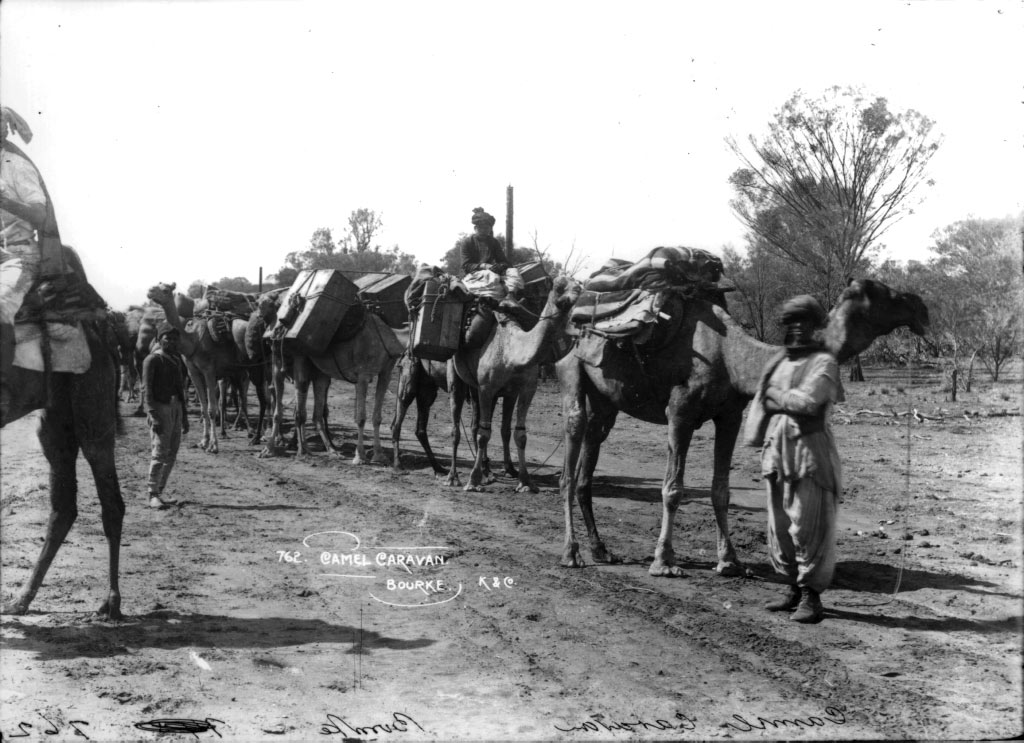

During this time railway lines were extended which enabled agricultural development, particularly wheat growing. Bores were sunk to access underground water, making it possible for stations to expand further into the semi-arid interior of New South Wales and central Queensland.

In this period, most pastoralists carried high numbers of stock, even in low rainfall areas. Sheep were cheap, water was available and graziers relied on saltbush and other scrub to provide quality feed when overgrazing had destroyed the perennial grasses.

Rabbit plague

Rabbits had been introduced to Victoria in 1859, and by the time drought set in they were in plague proportions across most parts of South-Eastern Australia.

Rabbits dug up the roots of native bushes and ringbarked trees and shrubs, killing them. The combination of overstocking, drought and rabbits meant that pastoralists had nothing left to feed their livestock.

With the ground cover gone, exposed topsoil was lifted in huge dust storms, which are a feature of most droughts in Australia.

AB ‘Banjo’ Patterson, ‘It’s Grand’, 1902:

It’s grand to be a rabbit

And breed till all is blue,

And then to die in heaps because

There’s nothing left to chew.

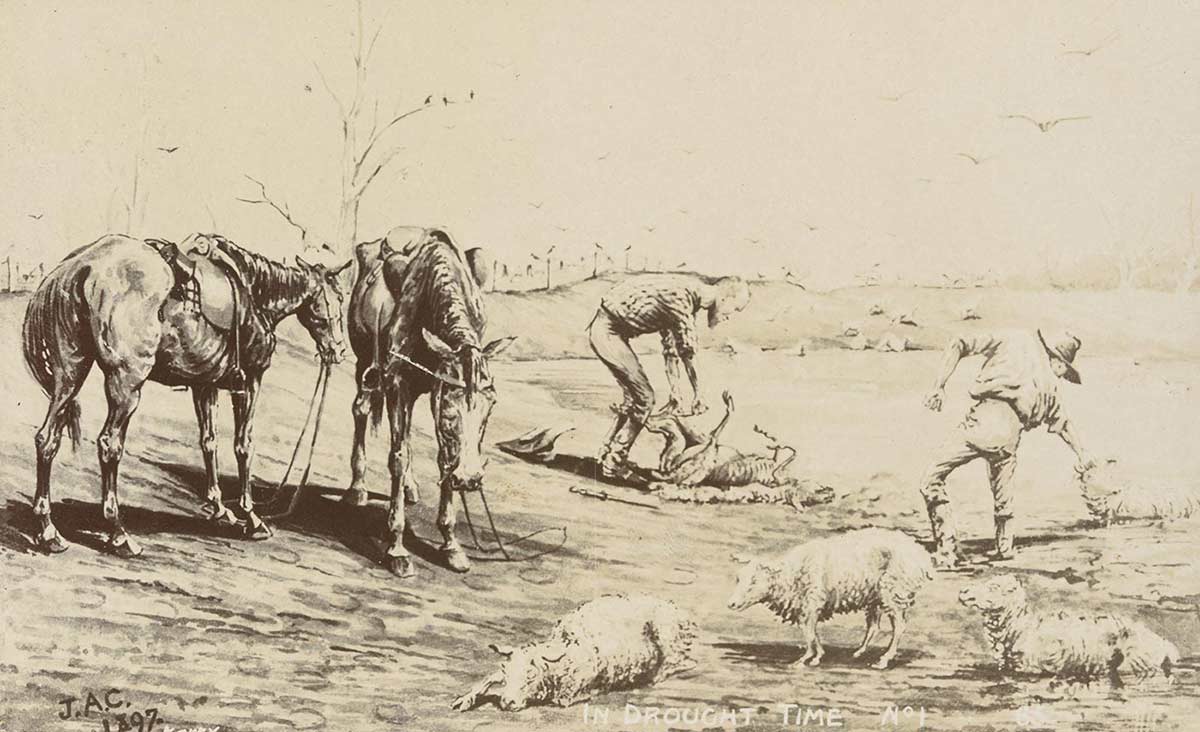

Stock losses

In 1892 Australia had 106 million sheep, two-thirds of which were in the eastern states. By 1903 the national flock had almost halved to 54 million. The nation lost more than 40 per cent of its cattle over the same period, nearly three million in Queensland alone.

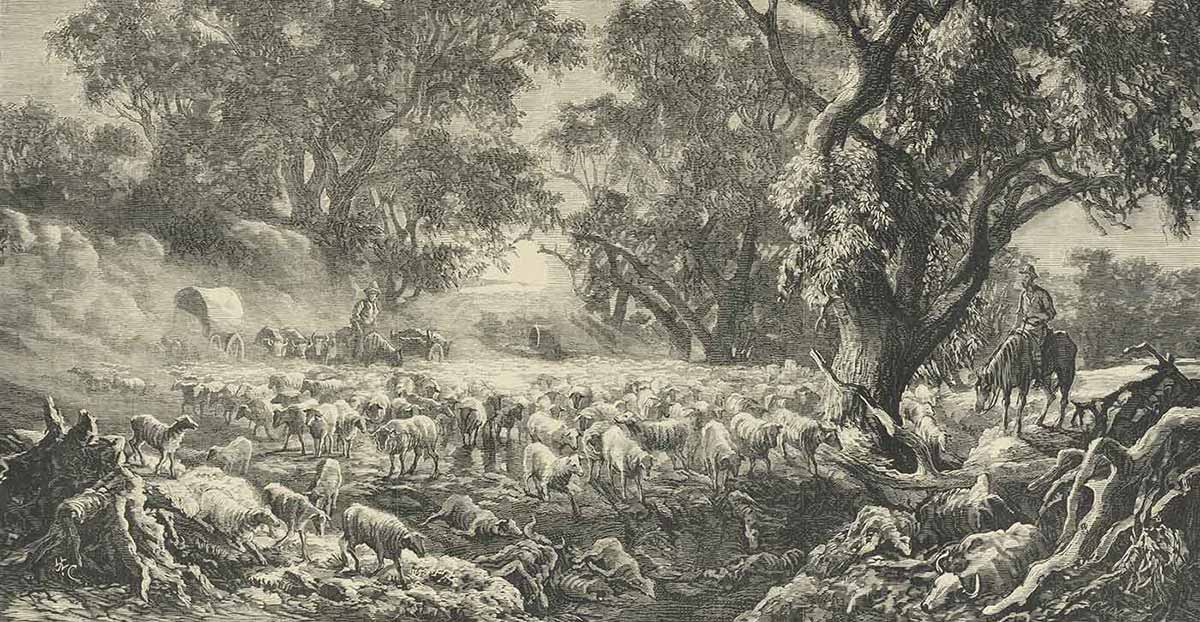

Drovers sought feed for hungry stock along travelling stock routes (known as the ‘long paddock’) or moved stock to pastures on the east coast and southern mountains where conditions were less dire.

Droving took an immense toll on sheep and cattle with losses of up to 70 per cent recorded, particularly in regions where watering points could be 100 kilometres apart. In 1902 local newspapers reported that more than 2,000 steers lay dead along the Goondiwindi to Miles route in Queensland.

Abandoned stations

Many pastoralists were overwhelmed by the debt they incurred buying feed, controlling rabbits and repairing infrastructure damaged by dust storms.

Banks foreclosed on some stations and many graziers walked off their land. Some five million acres of leasehold country in the NSW Western Division was reported to have been abandoned between 1891 and 1901.

AB ‘Banjo’ Patterson, ‘It’s Grand’, 1902:

It’s grand to be a Western man,

With shovel in your hand,

To dig your little homestead out

From underneath the sand.

Government response

No state government had a formal drought relief policy at this time and, although royal commissions and enquiries were held, governments were generally slow to consider practical measures.

The New South Wales Government declared a public holiday on 26 February 1902 so that people could ‘unite in humiliation and prayer’ for the end of the drought. Banks, government offices and most businesses closed, and special religious services were held.

The new federal government refused to reduce duties on fodder or to provide other drought assistance. Drought relief was seen as a state responsibility, a view which did not change until 1939 when the federal government assisted Tasmania to recover from bushfires during another severe drought.

Public appeals for relief

In October 1902 the Lord Mayor of Melbourne opened a public appeal for funds for the relief of Victoria’s drought-affected areas. By the time the appeal closed a year later, it had attracted close to £19,000 (around $2.7 million today) and had assisted 1670 families.

The Lord Mayor of Sydney started a relief fund in January 1903 which collected just over £23,000 (about $3.3 million) in a year.

Dame Nellie Melba, Australia’s internationally famous opera singer, donated the proceeds of her farewell performance at Sydney Town Hall on 18 March 1903 to the Lord Mayor’s Fund.

Dame Nellie Melba, November 1902:

I have seen with my own eyes the brown, burnt paddocks extending for hundreds of miles, with no vestige of grass left upon them. I have seen starving sheep leaning against the fences, too weak to move … It is simply appalling.

Pastoral industry changes

At the height of squatter-dominated pastoralism in 1880s, it was not uncommon for individual stations in New South Wales and Queensland to be up to 3,000 square kilometres in size and carry hundreds of thousands of merino sheep. Large pastoral investment companies were also prominent landholders in these states.

By the end of the drought, many of these huge stations had been resumed or foreclosed by banks and, under further land reforms aimed at encouraging closer settlement and the development of agriculture, they were partitioned and opened up to selectors.

Smaller properties and sheep flocks became the norm and mixed farming was widely adopted. It would be another 50 years before the national sheep flock recovered its pre-Federation Drought numbers.

Explore defining moments

References

Check your rainfall history, Bureau of Meteorology

Interactive: 100 years of drought in Australia, ABC News online

Don Garden, ‘The Federation Drought of 1895–1903, El Nino and society in Australia’, in (eds) Geneviève Massard-Guilbaud, Stephen Mosley, Common Ground: Integrating the Social and Environmental in History, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, 2010.

Michael McKernan, Drought: The Red Marauder, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2005.

Michael Pearson and Jane Lennon, Pastoral Australia: Fortunes, Failures and Hard Yakka: A Historical Overview 1788–1967, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, VIC, 2010.