For 150 years Australia relied on the British Empire for its external defence. But Britain’s military and strategic focus on Europe in the early 20th century caused many Australians to worry about a Japanese invasion of our resource-rich continent.

In the 1920s Britain, with support from Australia, formulated its Singapore Strategy whereby it would build a huge naval base on the island as a means of protecting its interests in the region.

The fall of Singapore in 1942 led the Australian Government to reconsider its alliance with Britain.

Gareth Evans, Minister for Foreign Affairs, 1994:

And it was only in late 1941 – when Curtin made his celebrated appeal to the United States – that Australia for the first time showed itself capable of addressing a fundamental issue about its place in the world other than reflexively, instinctively and dependently as a member of the British Empire.

Singapore Strategy

After the First World War, Australia re-evaluated its strategic position in the world and concluded that the greatest threat to national security lay with Japan and its desire to expand across the Pacific.

Many parts of Asia remained part of the British Empire, including India, Burma, Malaya and Hong Kong, all of which Britain wanted to protect from a Japanese advance.

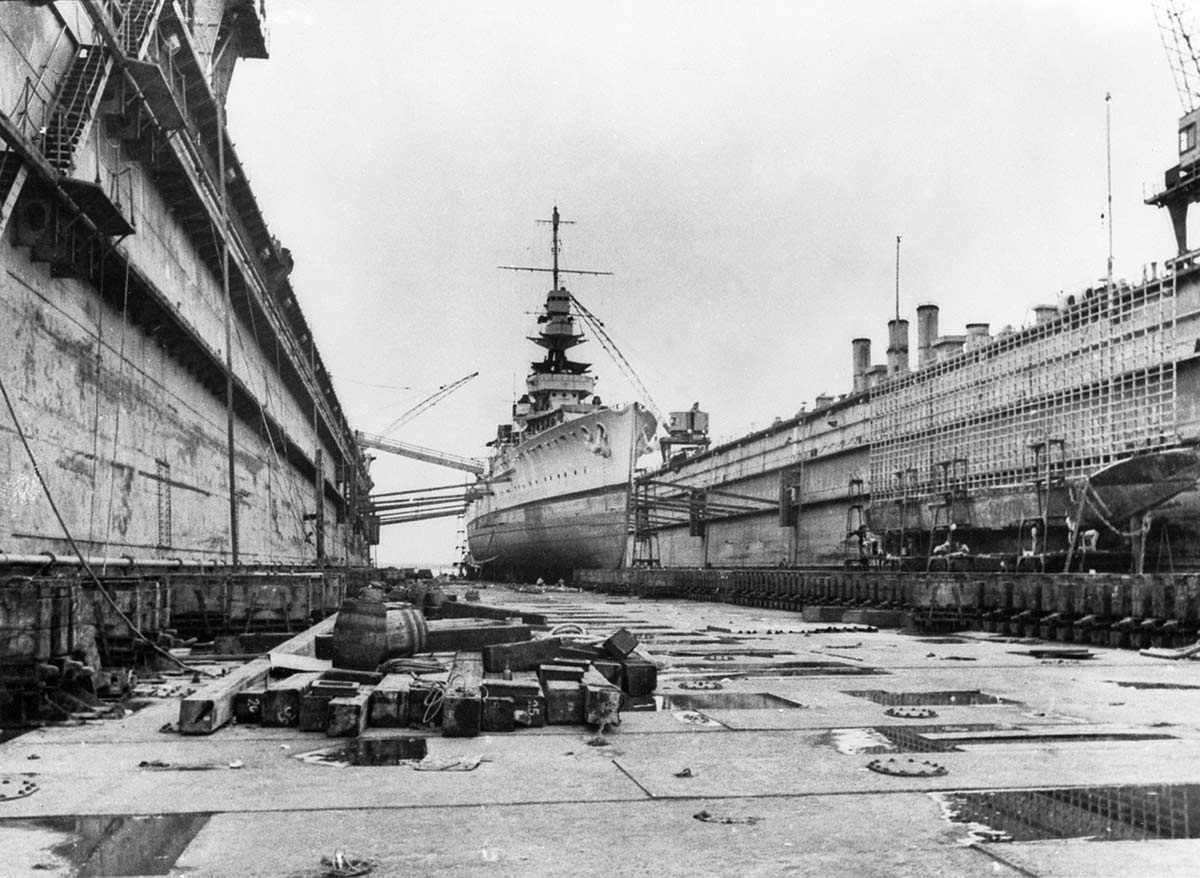

In 1919 Singapore, which is strategically located in the Strait of Malacca between the Pacific and Indian oceans, was chosen as the site of a major British naval base. The British anticipated that in the event of a Pacific war, they would relocate a large fleet of Royal Navy vessels from Britain to Singapore.

In 1923 construction began on the massive 54-square-kilometre base. Australia and New Zealand both invested in the construction of the facility.

Australia in Singapore

In Australia, the conservative Nationalist Party government of Stanley Bruce latched onto the Singapore Strategy as a way to reduce military spending.

Throughout the 1930s the Labor Party and some defence analysts opposed the scheme, saying that Australia should itself be building a larger navy rather than investing in a single base 6,000 kilometres from Sydney or Melbourne.

In 1936 the leader of the Labor Opposition, John Curtin, presciently stated that Japan was only likely to attack Singapore when Britain was preoccupied with a war in Europe.

At the start of the Second World War, Australia deployed most of its forces to assist British forces in Europe and North Africa. In February 1941, with the threat of an impending war with Japan, Australia dispatched the Eighth Division, four RAAF squadrons and eight warships to Singapore and Malaya.

Australian pilots were some of the first to engage with the Japanese when the Imperial Army invaded Malaya on 8 December 1941.

Problems with the Singapore Strategy

It was apparent even before the Japanese invasion of Malaya that the Singapore Strategy was in jeopardy.

Britain had been under threat from Germany since war broke out in 1939 and its resources were concentrated on its own preservation. The fleet of aircraft carriers and battleships that had been promised for the defence of the Empire’s eastern possessions was reduced to a single squadron centred around one battleship, HMS Prince of Wales, and one battlecruiser, HMS Repulse.

Japanese aircraft sunk both ships north of Singapore on 10 December 1941. This left the base without significant naval protection.

Battle for Singapore

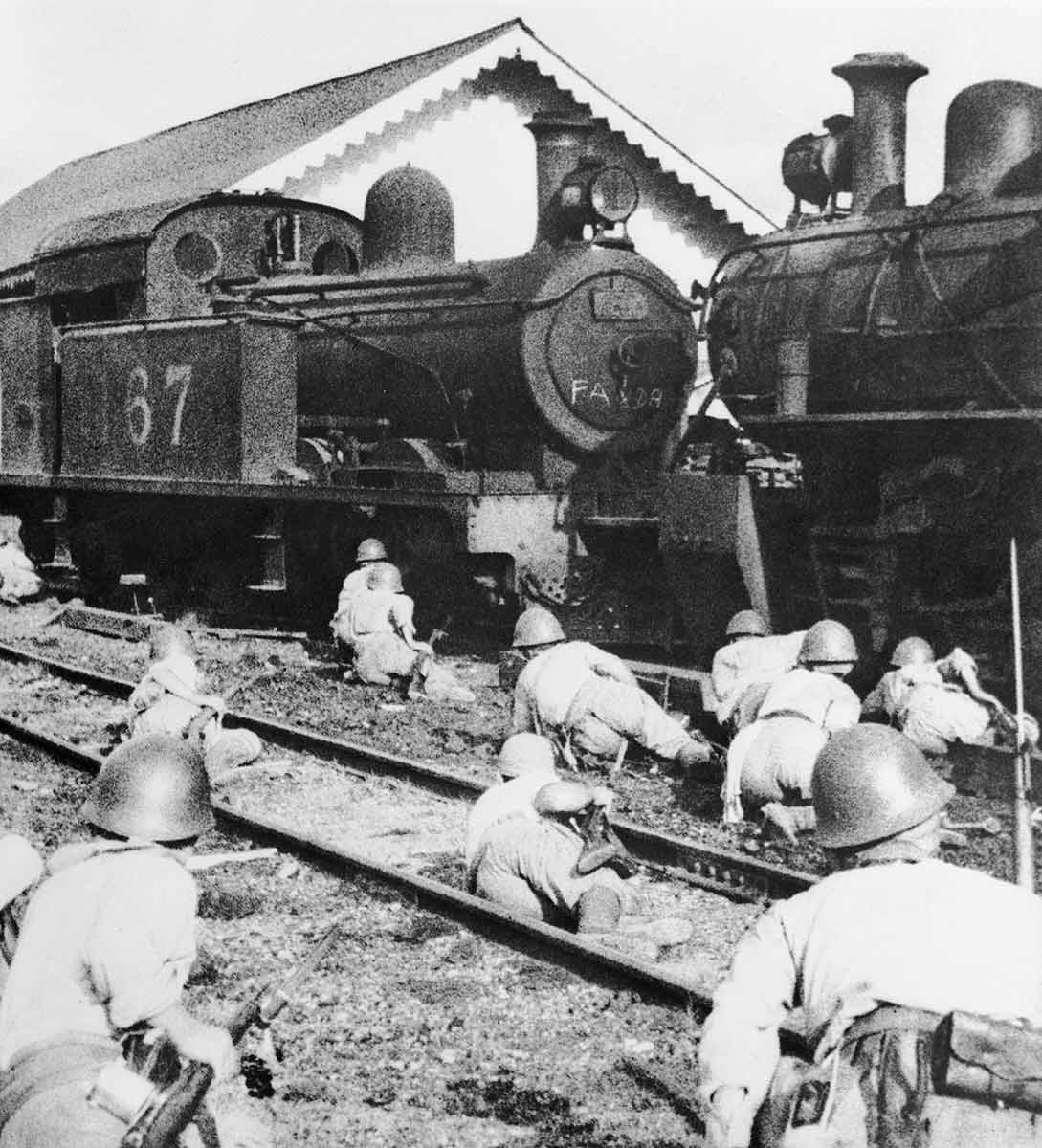

The Imperial Japanese Army invaded the Malay Peninsula on 8 December 1941, landing in the north at Khota Bharu in Malaya and Pattani and Songkhla in Thailand.

The Japanese were battle-hardened, well-organised and well-supported by air and armour; the inexperienced Allied forces could offer little resistance and the Japanese moved with incredible speed south along the peninsula.

Kuala Lumpur was taken on 11 January and Johore, capital of Malaya’s southern state, fell on 14 January. The Japanese had fought the 700 kilometres from their northern landings to the southern tip of the peninsula in less than two months.

On 31 January Allied forces withdrew across the causeway linking Malaya and Singapore. The defence of the island was poorly planned and executed.

Allied forces were spread too thin to resist the Japanese when they landed on the north-west of the island on 8 February. Allied air cover had been almost completely destroyed in the opening days of the campaign and so the city was being bombed at will.

Despite being heavily outnumbered, the Japanese moved quickly across the island. With one million citizens trapped in the city and water supplies at critical levels British commander Lieutenant General Arthur Percival surrendered on 15 February 1942. More than 130,000 Allied troops were taken prisoner.

The Japanese general Tomoyuki Yamashita had achieved a remarkable feat of arms.

In London, Prime Minister Winston Churchill announced that the fall of Singapore was the ‘worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history’.

For Australia too, the fall of Singapore was a disaster. More than 15,000 Australian soldiers were captured. Of these, more than 7,000 would die as prisoners of war. Controversially, the commander of Australian forces on the island, Major General Gordon Bennett, escaped the island with two staff officers on the night of the surrender.

Reappraisal of Australian foreign policy

The fall of Singapore was the final straw that brought about a paradigm shift in foreign policy for the Australian Government.

The strategic alignment away from Britain had been considered since the Japanese naval victory over Russia in 1905. This showed that Japan was potentially a more dominant force in the Pacific region than Britain. It led to Prime Minister Deakin’s invitation to the United States Navy’s ‘Great White Fleet’ to visit Australia in 1908.

However, after the conclusion of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, which had seen Japan enter the First World War on the side of the Allies, Australian conservative governments in the 1920s and 1930s continued to look to Britain to protect the country against a potential Japanese invasion.

However, the Singapore Strategy’s complete failure and the loss of almost a quarter of Australia's overseas soldiers at the very start of the Pacific War stunned the country and made consideration of a new foreign policy a priority.

In his new year’s address for 1942 Prime Minister Curtin announced:

Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom … we shall exert all our energies towards the shaping of a plan, with the United States as its keystone, which will give our country some confidence of being able to hold out until the tide of battle swings against the enemy.

This was the beginning of the Australian alliance with the United States – a partnership that continued throughout the Second World War, the Korean War, the Vietnam War and the Cold War, and remains at the heart of both major political parties’ security policies.

Renowned author Tom Keneally discusses the Fall of Singapore

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Fall of Singapore symposium audio

Justin Corfield and Robin Corfield, The Fall of Singapore, Hardie Grant Books, Sydney, 2012.

Brian Farrell, The Defence and Fall of Singapore 1940–42, The History Press, Brimscombe Port, UK, 2006.

Lionel Wigmore, The Japanese Thrust, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1957.