On 7 September 1936 the last known thylacine died at Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart. The thylacine had been granted protected status just two months before.

It is estimated there were about 5,000 thylacines in Tasmania at the time of European settlement. However, zealous hunting combined with factors such as habitat destruction and introduced disease, led to the rapid extinction of the species.

The Examiner (Launceston), 10 February 1937:

Has anybody seen a Tasmanian tiger lately? This is a question which the Animals and Birds Protection Board will shortly cause to be circulated throughout the state. Fears exist that this unique specimen of fauna may now be extinct … Mr A.W. Burbury said there was no reliable evidence that the Tasmanian tiger was now in existence.

Thylacines

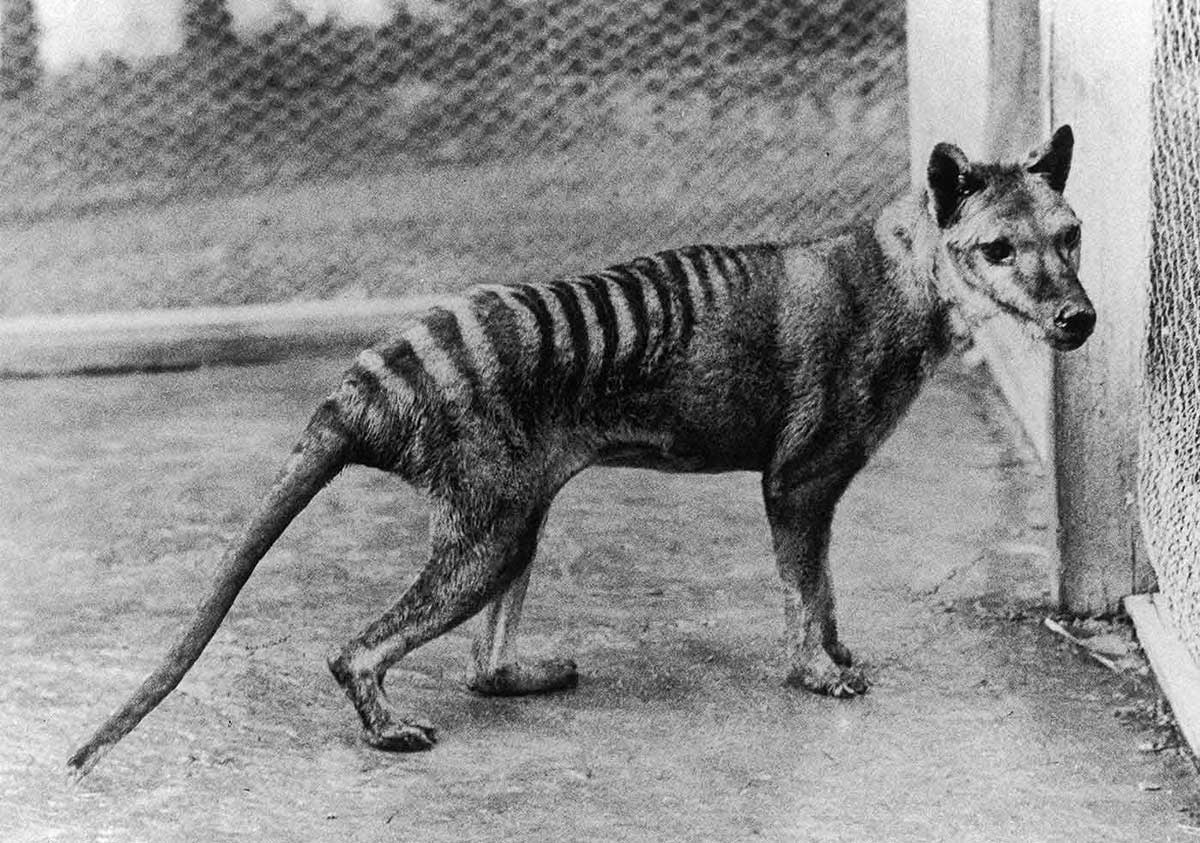

The name thylacine roughly translates (from the Greek via Latin) as ‘dog-headed pouched one’.

The thylacine was once the world’s largest marsupial carnivore. It was commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger, due to the distinctive stripes on its back.

Despite its fierce reputation, the thylacine was semi-nocturnal and was described as quite shy, usually avoiding contact with humans.

The fossilised remains of thylacines have been found in Papua New Guinea, throughout the Australian mainland and Tasmania.

Factors including the introduction of the dingo led to the extinction of the thylacine in all areas except Tasmania about 2,000 years ago. The thylacine population in Tasmania at the time of European settlement is estimated at about 5,000.

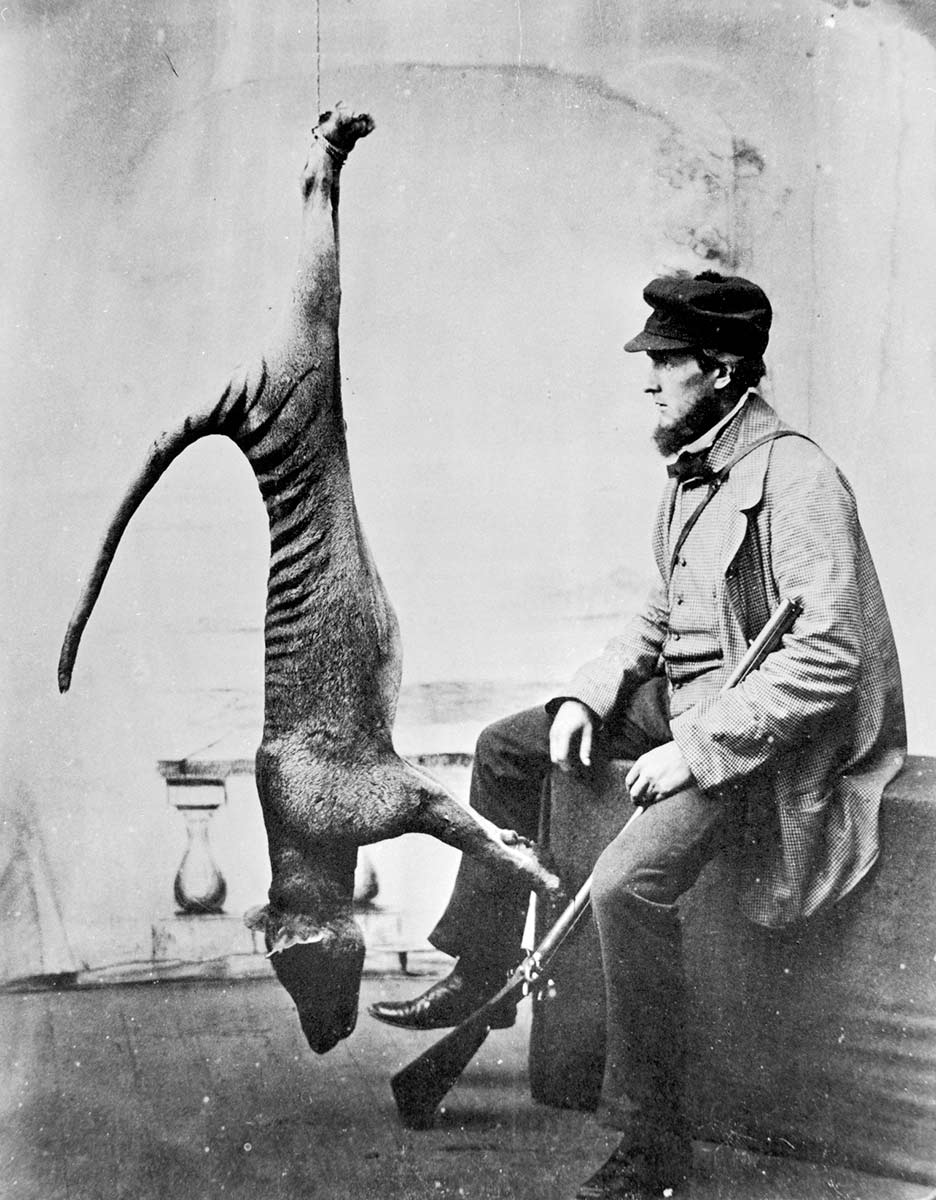

Bounties for thylacines

The establishment of European settlements in Tasmania in the early 1800s resulted in colonists clearing large areas of land and cultivating livestock such as sheep and cattle.

Despite evidence that feral dogs and widespread mismanagement were responsible for the majority of stock losses, the thylacine became an easy scapegoat and was hated and feared by Tasmanian settlers.

As early as 1830 bounty systems for the thylacine had been established, with farm owners pooling money to pay for skins. In 1888 the Tasmanian Government also introduced a bounty of £1 per full-grown animal and 10 shillings per juvenile animal destroyed. The program extended until 1909 and resulted in the awarding of more than 2,180 bounties.

It is estimated that at least 3,500 thylacines were killed through human hunting between 1830 and the 1920s. The introduction of competitive species such as wild dogs, foreign diseases including mange, and extensive habitat destruction also greatly contributed to thylacine population losses.

Note: Researchers in 2022 confirmed it was a myth that the last thylacine in Beaumaris Zoo, Hobart, was a male or named Benjamin.

Last of its kind?

The last known shooting of a wild thylacine took place in 1930, and by the mid part of that decade sightings in the wild were extremely rare. Authorities from scientific and zoological communities became concerned about the state of the decimated thylacine population and pushed for preservation measures to be undertaken.

However, a shift in public opinion and the start of conservation action came too late. The species was granted protected status just 59 days before the death of the last known thylacine, which died in Hobart's Beaumaris Zoo, possibly from exposure and neglect, on 7 September 1936.

Further efforts to capture specimens for zoos and museums were unsuccessful and none were ever found.

Since then, many expeditions have been organised to search for the thylacine in the Tasmanian wilderness and there continue to be many reported sightings by people who believe the animal is still about.

Despite this, there is no conclusive evidence of the continued existence of the thylacine and the animal has been officially extinct since 1986.

Thylacine de-extinction controversy

Today controversy surrounds the thylacine and its potential as a candidate for ‘de-extinction’. Various scientists have undertaken research into cloning the Tasmanian tiger and bringing the species ‘back from the dead’. Many arguments surround this process but the reality of producing a healthy thylacine from available DNA samples remains extremely expensive and complex.

The National Museum of Australia holds one of the most significant thylacine-related collections in the world, including what is believed to be the only surviving complete ‘wet specimen’ (a biological specimen kept in preserving fluid). Other pieces include two thylacine pelts, skeleton, and more than 30 body parts that were preserved by the Australian Institute of Anatomy.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

‘The discovery of the remains of the last Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus)’ by Robert N. Paddle and Kathryn M. Medlock, in Australian Zoologist, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2023, 97-108

Thylacine mystery solved in TMAG collection, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, 2022

Thylacines, Tasmanian Parks & Wildlife Service

Second chance for Tasmanian tigers TedX DeExtinction talk by Michael Archer, YouTube

David Owen, Thylacine: The Tragic Tale of the Tasmanian Tiger, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2003.

Robert Paddle, The Last Tasmanian Tiger: The History and Extinction of the Thylacine, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2000.