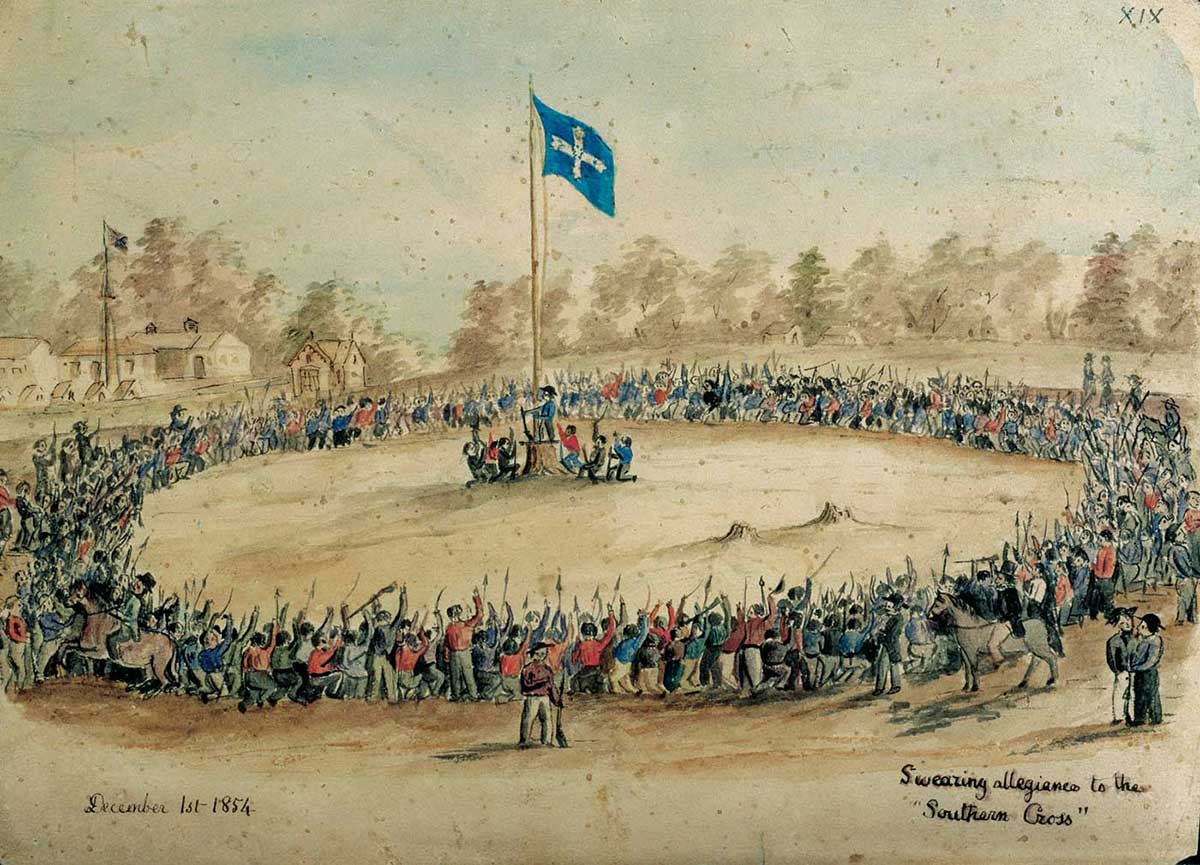

On 29 November 1854 miners at Ballarat in Victoria first raised the Southern Cross flag at Bakery Hill and began building a stockade at the nearby Eureka diggings. They were disgruntled with the way the colonial government was administering the goldfields.

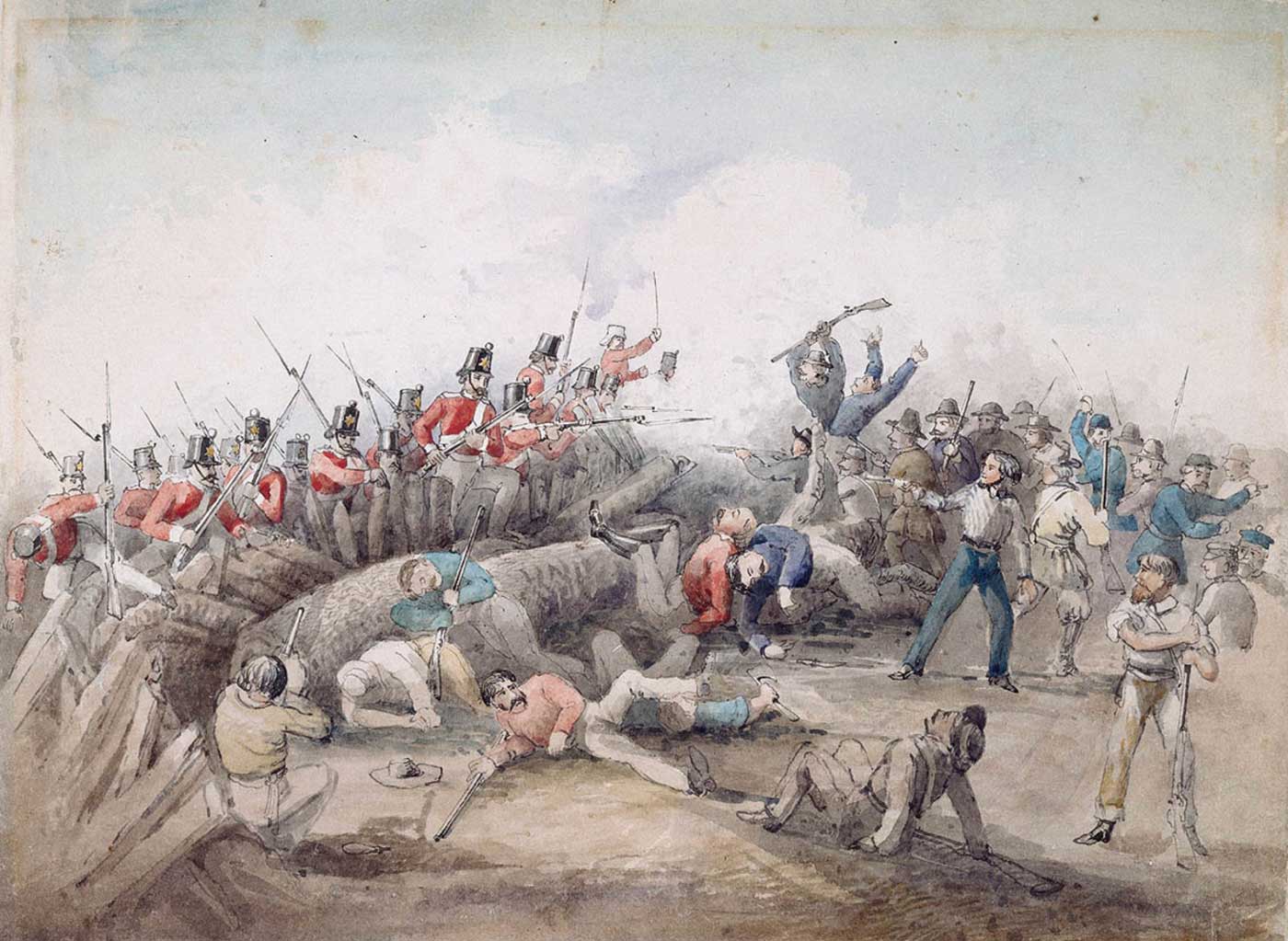

Early on the morning of Sunday 3 December 1854, when the stockade was only lightly guarded, government troops attacked. At least 22 miners and five soldiers were killed.

The rebellion of miners at Eureka Stockade is a key event in the development of Australia’s political systems and attitudes towards democracy and equality.

Eureka leader Peter Lalor, December 1854:

It is my duty now to swear you in, and to take with you the oath to be faithful to the Southern Cross. Now hear me with attention. The man who, after this solemn oath does not stand by our standard, is a coward at heart … We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other, and fight to defend our rights and liberties.

The rebellion at Eureka Stockade in live-sketch animation, as told by historian David Hunt. Note: It is believed that five or six soldiers died at the stockade.

Discovery of gold in Australia

In early 1851 the New South Wales government announced that gold had been discovered near Bathurst by Edward Hargreaves, John Lister and William, James and Henry Tom. In June 1851 the Victorian government also reported discoveries of gold.

In the 19th century gold was a catalyst for great change in Australia. The belief that you could dig your own fortune attracted people from across the country and around the world.

In the years between 1851 and 1860, Victoria’s population increased from 76,000 to 540,000.

This massive influx of people was a serious challenge for the government. There were limited finances to provide services to citizens and the colonial budget was in deficit.

Introduction of gold licence

To raise funds, but also to discourage the flood of people moving to the diggings, New South Wales Governor Charles Fitzroy and Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe of Victoria, imposed a 30-shilling a month licence fee on miners.

This was a substantial sum for most miners. When the easily obtainable surface gold began to run out in 1852, the licence fee became a point of contention.

In 1852, the 35,000 miners on the Victorian goldfields were producing about 5 ounces of gold per head. By 1854 the population had almost tripled while production had dropped to 1.5 ounces per head.

Conflict on the goldfields

From 1853 miners began to gather at ‘monster’ meetings to voice their concerns about the licencing system. They alleged the police were extorting money, accepting bribes and imprisoning people without due process. Delegations presented their concerns to Governor La Trobe, but he was unreceptive to the requests.

Many of the miners were politically engaged – some had participated in the Chartist movement for political reform in Britain during the 1830s and 1840s. Others had been involved in the anti-authoritarian revolutions that spread across Europe in 1848.

The situation on the goldfields was tense as police regularly ran ‘licence hunts’ to track down miners who hadn’t paid their fees.

Murder at the Eureka Hotel

In the early hours of 7 October 1854, Scottish miner James Scobie was killed in an altercation at the Eureka Hotel in Ballarat. The proprietor, James Bentley, was accused of killing Scobie.

A court of inquiry was held and Bentley was quickly exonerated. The miners sensed a miscarriage of justice, in part because one of the court members, John D’Ewes, was a police magistrate known to have taken bribes from Bentley.

On 17 October 1854 about 5,000 people gathered to discuss the case. They decided to appeal against the decision. After the dispersal of the crowd, a small group decided to set fire to the Eureka Hotel. They were arrested by police and the situation became more tense.

Eureka and the Southern Cross flag

Over the next weeks the miners met and elected delegates. On 27 November 1854 the delegates approached the new Victorian Governor, Charles Hotham.

The delegation demanded the release of the men who burned down Bentley’s Eureka Hotel. Governor Hotham took offence to having demands made of him and dismissed the grievances. He sent 150 British soldiers of the 40th Regiment of Foot to Ballarat to reinforce the police and soldiers already stationed there.

Sensing a change in the government’s approach, the miners held another meeting on 29 November 1854 at Bakery Hill. There, the newly created Eureka flag was unfurled. The use of the flag, featuring a depiction of the Southern Cross on a navy background, has become a symbol of the labour movement in Australia.

Eureka Stockade

The police were unsettled by the hostility building among the miners and decided to implement a licence hunt the next day. On the morning of 30 November 1854, as police moved through the camp, the miners decided they’d had enough.

The miners gathered and marched to Bakery Hill. There, Irish miner Peter Lalor became the leader of the protest. Lalor led the miners to the Eureka diggings, where the men and women joined him in an oath: ‘We swear by the Southern Cross, to stand truly by each other, and fight to defend our rights and liberties’.

The miners gathered timber from nearby mineshafts and built a protective stockade.

Conflict at Eureka

Over the next two days, men and women remained in and around the stockade, many performing military drills in preparation for possible conflict. This was too much for the Commissioner of the Ballarat goldfields, Robert Rede. He called for the police and army to destroy the stockade at first light on Sunday 3 December 1854.

That morning almost 300 mounted and foot troopers, and police attacked the stockade. The assault was over in 15 minutes, with at least 22 miners – including one woman – and five soldiers losing their lives.

Eureka arrests and trials

Police arrested and detained 113 of the miners involved in the Eureka Stockade. Eventually 13 were taken to Melbourne to stand trial. Governor Hotham called for a Goldfields Commission of Enquiry on 7 December 1854.

The citizens of Victoria were opposed to the government's actions at Ballarat and one by one the 13 leaders of the rebellion were tried by jury and released.

Goldfields Commission of Enquiry

In March 1855 the Commission of Enquiry released its recommendations. The licence fee was removed, replaced by an export duty and a nominal £1 per year miner’s right. Half the police on the goldfields were fired and one warden replaced the multitude of gold commissioners (who had issued the licences), many of whom were corrupt.

Twelve new members were added to the Victorian Legislative Council, four appointed by the Queen and eight elected by people who held a miner’s right. One of these elected members was Peter Lalor.

Legacy of the Eureka Stockade

The Eureka Stockade was a short-lived rebellion that continues to influence Australian politics to this day. Decades later Doc Evatt, former Leader of the Australian Labor Party and High Court judge, would pronounce that ‘Australian democracy was born at Eureka.’

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

The Eureka Flag, Eureka Centre Ballarat

Gold miners and mining research guide, State Library of Victoria

Peter Lalor, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Raffaello Carboni, The Eureka Stockade, Miegunyah Press, Carlton, Victoria, 2004.

Manning Clark, A History of Australia, vol. 4, Melbourne University Publishing, 1995.

Geoffrey Serle, The Rush to be Rich, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1971.

Clare Wright, The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka, Text Publishing, 2013.

Frauenfelder, P. ed., Eureka Stockade: As reported in the pages of the Argus newspaper, Education Centre, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, 1998