In 1972 Australian unions and the newly elected Whitlam government lobbied the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Commission (ACAC) to reevaluate their earlier decision granting equal pay to women only in those instances where they did exactly the same work as men.

The ACAC agreed to a review in which they granted women equal pay for work of equal value to men.

This meant that traditionally female roles began to be assessed for their contribution to a workplace or industry, instead of their level of resemblance to traditionally male roles.

ACAC ruling on the National Wage and Equal Pay cases, 1972:

The principle of ‘equal pay for work of equal value’ will be applied to all awards of the Commission. By ‘equal pay for work of equal value’ we mean the fixation of award wage rates by a consideration of the work performed irrespective of the sex of the worker.

Women in the Second World War

During the Second World War, many Australian women joined the workforce, filling essential industry positions left vacant by men who had gone overseas to serve. In doing so, they performed duties that were usually considered part of the male domain, including farming, building and manufacturing.

These workers formed women’s employment organisations to fight for their working conditions and rights. In 1943 their lobbying led the Australian Government to establish the Women’s Employment Board and secured women 75 per cent of the male wage for performing the same jobs. Prior to this, women had been receiving around two-thirds (or less) of the male wage.

This was considered an excellent outcome and many women were happy to be working and earning money while also aiding the war effort. Female participation in the workforce greatly decreased after the war, when men returned from serving and resumed their old positions.

This had an impact on the wages of women as many returned to lower-paying jobs with fewer benefits and stricter working conditions, including the requirement that women resign on getting married.

Equal Remuneration Convention

In 1951 the International Labour Organization, a United Nations agency, released the Equal Remuneration Convention.

This convention stated that both sexes were entitled to ‘equal remuneration … for work of equal value … with a view to providing a classification of jobs without regard to sex’. In other words, it recommended that jobs (and their remuneration) be classified according to the nature of the work rather than who performed it.

Some countries had already legislated for equal pay before the release of the convention, like France (1946) and Germany (1949). Workers from other nations, including Australia, cited the convention when lobbying for more equal wage distribution between the sexes.

The United Nations also included a demand for wage equality and equal pay in Article 7 of the International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 1954.

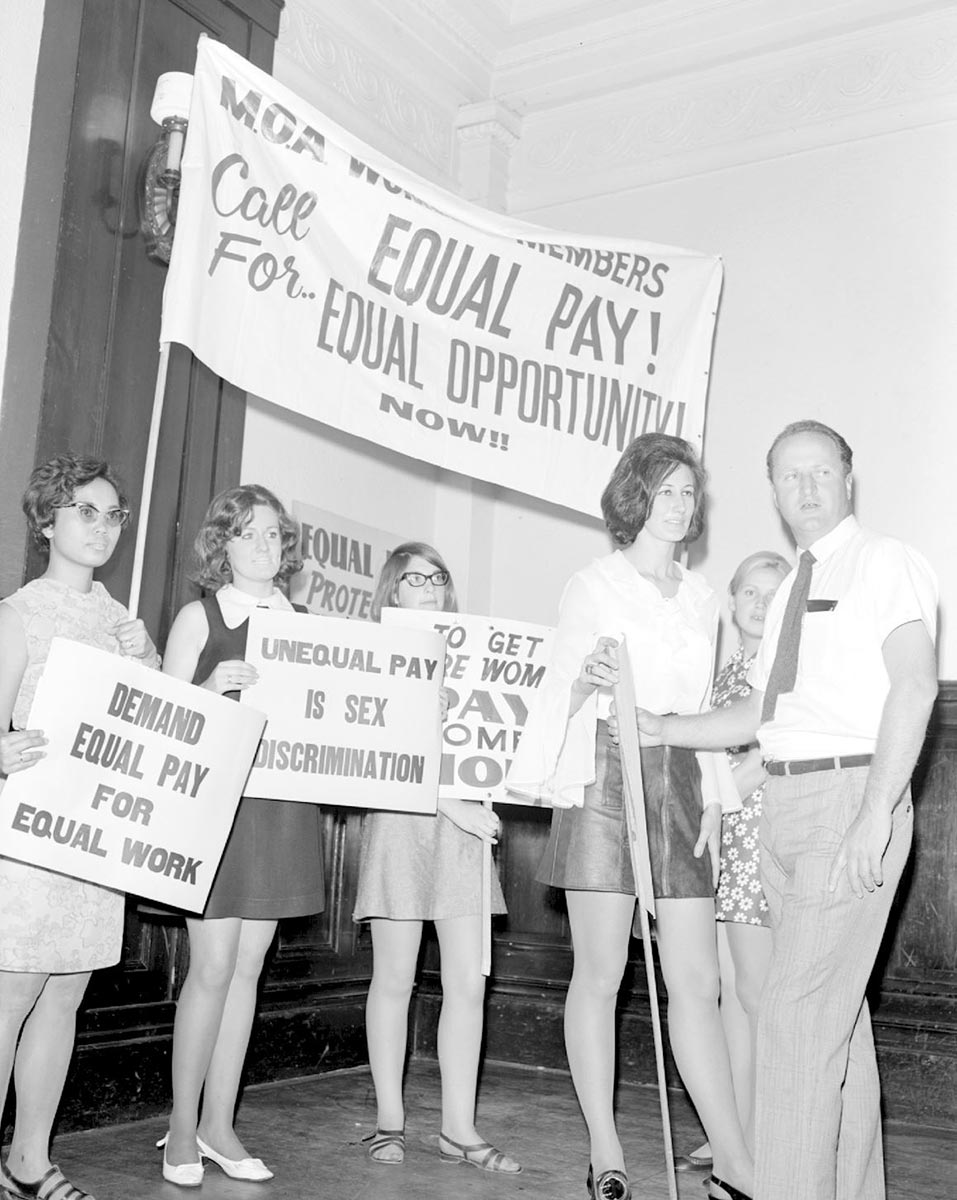

During the 1950s and 60s both men and women in Australia participated in protests calling on the government to ratify the 1951 convention and make equal pay the law in Australia.

1969 ACAC equal pay ruling

It wasn’t until 1969 that any real progress was made. In that year, the Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union and other workers’ groups brought a case to the ACAC against the Meat and Allied Trades Federation (and others) arguing for equal pay for all employees.

The ruling of the commission, which applied nationally, established the general female award minimum wage at 85 per cent of the male wage.

This was in recognition of the ‘breadwinner’ component of male pay rates, which assumed that men needed to be paid extra to provide for their family as married women generally did not work outside of the home.

The ruling stipulated that in cases where men were performing work usually reserved for females, they were entitled to a higher wage than their female colleagues.

The 1969 decision did, however, secure equal pay for women in instances where they were assessed as doing exactly the same work as men in traditionally male roles. For example, women who worked on an abattoir floor handling meat were now paid the same wage as the men they worked with.

All other women received the nationally instituted 85 per cent. For instance, women who held office jobs in the same abattoir would earn less than their male colleagues.

Research completed in time for the 1972 review of this decision noted that only 18 per cent of women were assessed as performing work equal to that of a man, therefore severely limiting the number of female workers who actually benefited from the part of the 1969 ruling that allowed for wage equality between the sexes.

1972 equal pay decision review

In Australia, the influence of trade unions on the introduction of equal pay was significant. The first Commission ruling in 1969 was a direct result of union action, and it was after unions, and the newly elected Whitlam Labor government, again approached ACAC that the 1972 review was undertaken.

In 1972 the commission ruled that women and men undertaking similar work that had similar value were eligible for the same rate.

In theory, this meant that if the value of work in a recognised ‘female industry’ was acknowledged by the Commission to be similar in value to the work in a ‘male’ industry, women would earn the same amount. In practice, it was a struggle for women and their supporters to have the value of jobs classified as ‘female roles’ assessed fairly.

In addition, the commission’s 1972 decision only applied to women working under federal awards and conditions – about 40 per cent of the female workforce.

To expand the reach of the Commission’s decision, union groups continued to lobby state governments to change their legislation to benefit female employees. New South Wales was the first state to do so.

Addressing the gender pay gap

While the introduction of ‘equal pay for work of equal value’ was an important step towards equality between the sexes in the workforce, many changes were still required before Australian women moved closer to true pay equality.

In 1973 a ruling by the commission finally granted an equal minimum wage to all Australians, regardless of their sex, and in 1974 the ‘breadwinner’ component of a male wage was removed in recognition of the fact that more Australian women were providing for their families.

However, there is still a wage gap between the average earnings of men and women. In 2012 Fair Work Australia moved to address the fact that the average income of Australian women was still around 17 per cent less than the male average by gradually increasing the amount that people earn in industries that are still dominated by women, like teaching and nursing.

In our collection

You may also like

References

Equal Remuneration Convention, International Labour Organization

Economic Society of Australia and New Zealand, The Australian Experience of the Implementation of Equal Pay for Women: A Reassessment, 1981.

Anne Summers, The End of Equality: Work, Babies and Women’s Choices in 21st Century Australia, Random House Australia, 2003.