In the 1949 federal election the Liberal Party, under the leadership of Robert Menzies, defeated Labor in a campaign targeting what it considered to be undue government intervention in the economy and society.

Ben Chifley’s Labor Party had won a decisive victory in the 1946 election but unpopular policies and a tumultuous domestic environment let the newly formed Liberal Party win a hotly contested poll.

So began the Liberals’ 23-year term as Australia’s ruling party, led for 17 of those years by Prime Minister Menzies.

Robert Menzies on Prime Minister Chifley’s Banking Bill, 1947:

This Bill goes far beyond banking. It will have an operation and effect far beyond the business of money changing. This bill will be a tremendous step towards the servile State, because it will set aside normal liberty of choice, and that is what competition means, and will forward the idea of special supremacy of government. That is the antithesis of democracy.

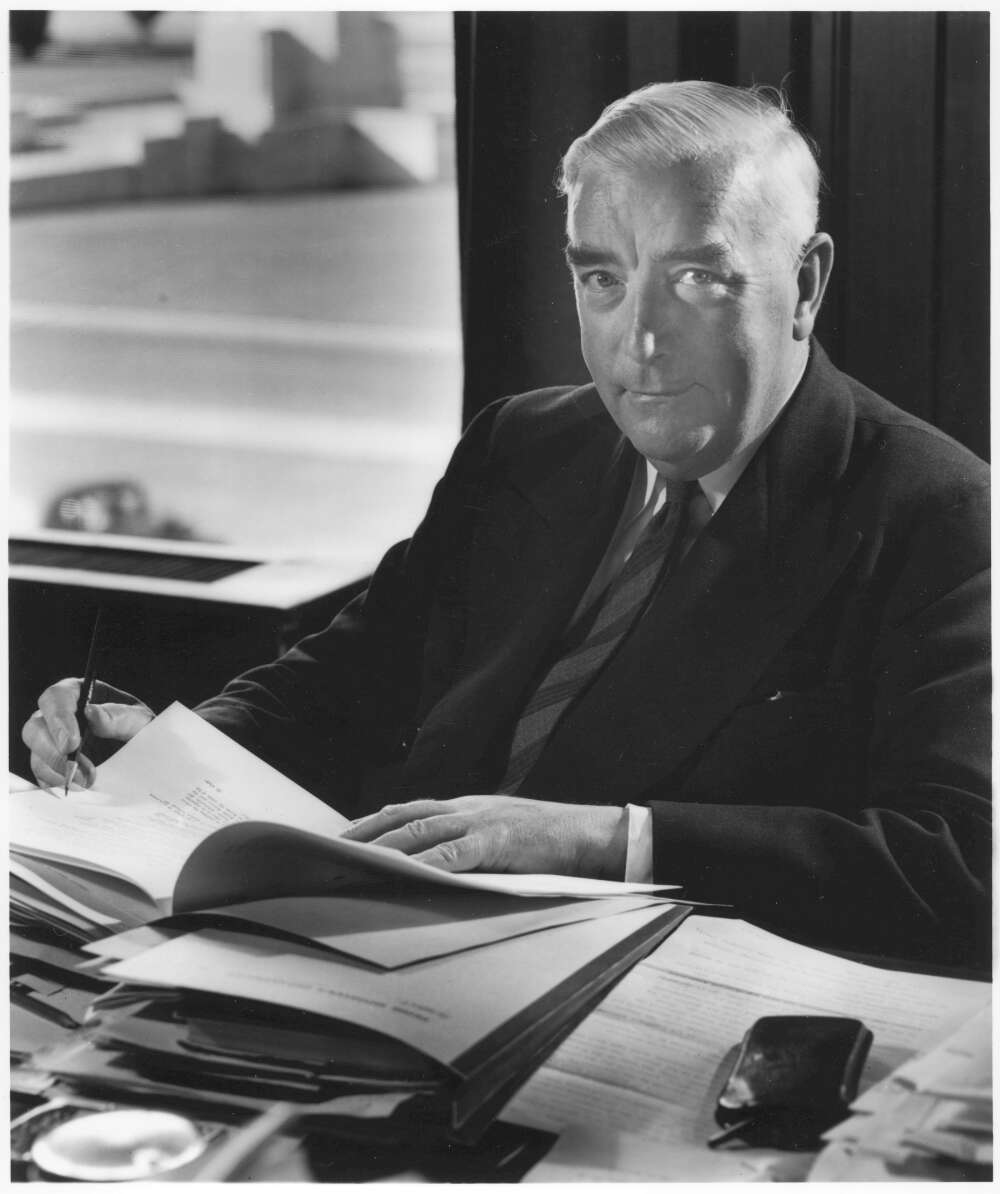

Robert Menzies

Robert Menzies first served as Australia’s Prime Minister after the death in office of the United Australia Party (UAP) leader, Joseph Lyons in April 1939. When Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September, Prime Minister Menzies announced just hours later:

Fellow Australians, It is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that in consequence of a persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.

The formation of the Second Australian Imperial Force began within two weeks. Tragedy struck for the government when on 13 August 1940 a plane carrying three Cabinet ministers and the Chief of the General Staff crashed on landing in Canberra.

The disaster prompted Menzies to call an early federal election the following month, which saw the UAP hold on to power but only with the assistance of two independent Members of Parliament (MPs).

In January 1941 Menzies travelled to Britain despite the instability of his minority government.

On his return in May he reached out to the Labor Party to form a combined national government. Labor rejected the proposals and Menzies began to lose control of his government. On 29 August he resigned as Prime Minister and Arthur Fadden, leader of the Country Party, took over.

In October the two independent MPs voted against Fadden’s budget and brought down the government.

The Governor-General, Lord Gowrie, was reluctant to call an election because of the war and after securing support from the independent MPs for a new Labor government swore in John Curtin as Prime Minister on 7 October 1941.

Formation of the Liberal Party

In the 1943 federal election the UAP/Country Party coalition, now led by the wily old ex-Prime Minister Billy Hughes, suffered a devastating defeat, losing 18 seats to the Labor Party.

It was apparent the UAP was in decline and a group of supporters under the leadership of Menzies began building a new anti-socialist party. It would be a self-financing, truly national organisation supportive of free enterprise but tempered by limited government involvement in the economy.

The Liberal Party was founded in late 1944. However, with the next federal election scheduled for September 1946, the new party had little time to organise its campaign and endured a significant loss. Menzies, who was Liberal Party leader, seriously contemplated retirement from public life.

Chifley’s postwar plans

It was the Labor government’s postwar plans to increase government intervention in health, family, business, law and banking that reinvigorated the Liberal Party membership.

In July 1945 John Curtin died in office and Ben Chifley took over as Prime Minister.

Chifley had been Treasurer and Minister for Post War Reconstruction in Curtin’s government. He had definite ideas about the country’s peacetime development and initiated a series of radical proposals to forward his agenda.

The centrepieces of the government’s legislative plans were the Banking and the Commonwealth Bank Acts of 1945.

These laws provided the government with final control over monetary policy and recognised the Commonwealth Bank as Australia’s central bank with the power to regulate private trading banks through a council selected by government.

The legislation passed despite being controversial. Then in October 1947 Chifley introduced legislation to nationalise all banks.

The Opposition reacted strongly, with Menzies claiming that this was now the, ‘second battle for Australia,’ and Earle Page, leader of the Country Party, saying that his supporters might use ‘physical means’ to oppose it.

The proposed legislation was blamed for the downfall of the Victoria Labor government that year. The High Court declared the law invalid, but the spectre of nationalisation provided the Liberal/Country Party coalition with an issue to rally around as the party’s electoral organisation mobilised for the 1949 election.

Mining strike and fuel rationing

On 27 June 1949, 23,000 coalminers went on strike. The miners were supported by the Communist Party of Australia and bargaining between the government and the unions quickly stalled. Eventually the government decided to use Australian military forces for the first time to break a peacetime strike and on 1 August brought in 2500 troops to work the mines.

Menzies immediately realised the political advantage of the situation and was able to claim that Labor was both pro-communist in relation to the bank nationalisation and anti-union with regard to the miners’ action.

The strike lasted seven long weeks. Then on 15 November, only a day after he had given a major policy speech predicting tighter economic controls, Chifley reintroduced petrol rationing. People sensed a slide back to wartime government control over all aspects of life and Menzies was able to provide a hopeful alternative vision.

In the federal election of 10 December the Liberal/Country Party coalition won an historic victory, increasing their total vote by 10.8 per cent and winning 74 seats in the House of Representatives to Labor’s 47. It was the start of 23 years of continuous coalition government in Australia, 17 of them under Prime Minister Robert Menzies.

Australia under Menzies

Among Menzies’ key policies was to stamp out Communist influence in the union movement and end disruption caused by strike action – goals he felt could be achieved by abolishing the Communist Party. His legislation was overturned by the High Court in 1951 so Menzies took it to a referendum, which was narrowly defeated.

From the mid-1960s, Australia’s economic boom continued with the discovery and exploitation of new mineral and petroleum resources. Two major public spectacles of the mid-1950s became the focus of national attention: the visit of Queen Elizabeth II in 1954 and the Melbourne Olympic Games two years later. Both events were strongly promoted by the government.

The commitment of the Menzies government to its alliances with the UK led to Britain testing its nuclear weapons in central Australia from 1952 to 1963. However, Australia also forged closer links with the USA, signing the ANZUS treaty in 1951 and sending its troops to war in Korea and Vietnam.

Menzies’ long tenure was helped in part by global economic prosperity and the 1955 split in the Labor Party. For all that, his government’s own policies contributed to economic development and Menzies enjoyed strong support in his own right, effectively appealing to Australia’s burgeoning middle class who he referred to as the 'Forgotten People'.

The Menzies era was characterised by social conservatism. However, it was also a period of sustained economic growth, technological innovation and gradual cultural change. The growth in immigration and international communication reduced white Australia’s allegiance to its British heritage.

Television, the Melbourne Olympics, and new forms of music and art led Australians to reconsider their place in the world; and although the Prime Minister’s devotion to the British monarchy was undying, Australia began to develop its own independent identity.

In 1966 Menzies decided to retire. He is still Australia’s longest serving prime minister.

In our collection

References

Menzies in the Australian Dictionary of Biography

Robert Menzies on our Prime Ministers website

Fred Alexander, From Curtin to Menzies and After: Continuity or Confrontation, Thomas Nelson (Australia) Melbourne, 1973.

Judith Brett, Australian Liberals and the Moral Middle Class: From Alfred Deakin to John Howard, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003.

AW Martin, Robert Menzies: A Life, vol. 2, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1999.