In September 1940, 2542 ‘enemy aliens’ from Britain disembarked HMT Dunera in Melbourne and Sydney. Most were Jewish refugees who had fled Nazi persecution in Germany and Austria. They were interned in camps near Hay and Orange in NSW and Tatura in Victoria.

The ‘Dunera Boys’, as they became known, included musicians, artists, philosophers, scientists and writers. Following their release in 1941 many chose to remain in Australia, making a significant contribution to the nation’s economic, social and cultural life.

Sydney Morning Herald, 19 May 2006:

Their arrival in Australia – after a 57-day journey in appalling conditions – was seen as the greatest injection of talent to enter Australia on a single vessel.

Internment in Britain

When Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, more than 70,000 Germans and Austrians resident in the United Kingdom became enemy aliens. Initially, the British Government set up tribunals to determine the threat these people posed to Britain.

The government decided on three classifications of aliens:

- 66,000 were deemed Category C, which meant they posed the least danger and were exempt from internment or restrictions

- 6,700 were classified as Category B and monitored by the police

- 569 were classified as Category A and interned as enemy aliens.

In May 1940, with the German army advancing through Belgium and France and the growing possibility of an invasion, the British Government reassessed the enemy alien population and interned a further 12,000 Germans, Austrians and Italians.

This dramatic increase in internees led to severe overcrowding. To relieve this, 7500 internees were shipped to Australia and Canada between 24 June and 10 July 1940.

Tragically, the Arandora Star, one of these transports bound for Canada and carrying more than 1,000 internees and 300 crew, was torpedoed and sunk on 2 July 1940. Eight hundred and five people were killed.

HMT Dunera

On 10 July 1940, 2542 detainees were embarked aboard the Hired Military Transport (HMT) Dunera at Liverpool bound for Australia.

Among the group were 450 German and Italian prisoners of war and a few dozen fascist sympathisers, but the vast majority of the deportees were anti-fascist and two-thirds were Jewish. Also included were some of the survivors from the Arandora Star.

The treatment of internees on board the transport was appalling. The 309 poorly trained and led soldiers on guard stole possessions and documents, many of which were thrown overboard. Internees were allowed above decks into the fresh air for only 30 minutes a day. With only 10 toilets for more than 2500 men, human waste flowed across the decks.

Internees were beaten and verbally abused. Klaus Wilcynski recalls that soldiers smashed beer bottles on the deck and forced the internees to walk across the broken glass barefoot.

Their treatment was so poor that the British Government eventually agreed to pay £35,000 in compensation to the group. Three of the guards, including officer-in-charge Lieutenant-Colonel William Scott, were court martialled.

Arrival in Australia

On 3 September 1940 Dunera docked in Port Melbourne where 344 internees disembarked. The remainder of the detainees were taken to Sydney, arriving on 6 September. From there they boarded trains to the central New South Wales town of Hay.

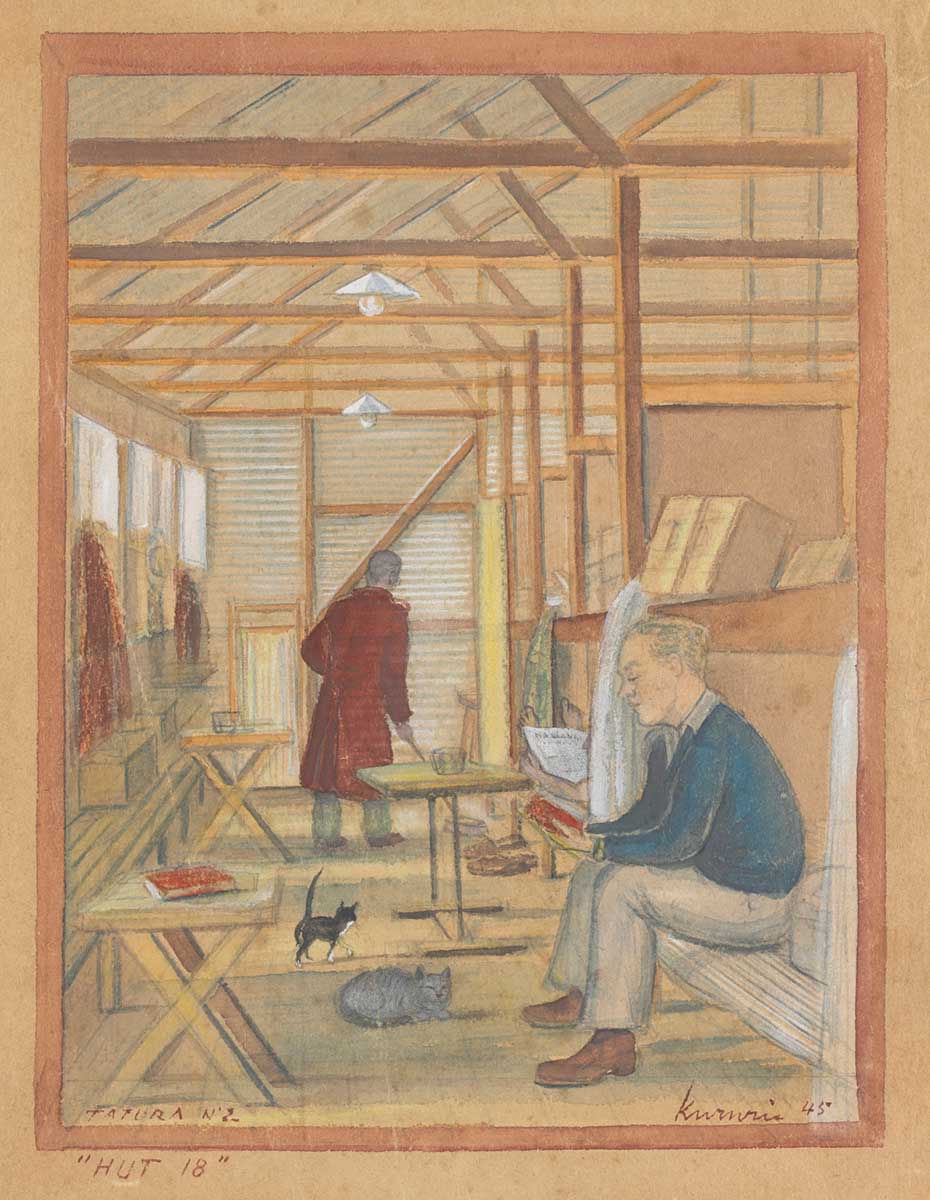

The Hay camp held most of the internees. It comprised three compounds, each holding 1,000 people. The group had a high percentage of skilled professionals, tradesmen and artists as many of the Jewish inmates had been forced to leave successful careers in Germany, Austria and England in the preceding years.

The internees established an unofficial university, libraries and orchestras, and they held concerts and theatre performances, published a newspaper and even minted a currency for use inside the camp.

Release from detention

Within weeks of the Dunera’s departure, the British Government altered its alien classification system once more. Under the new system, most of the Dunera internees would not have been transported. By October 1940 the British Government was expressing regret for the internment of the majority of the detainees.

Australia’s Governor-General Lord Gowrie wrote to King George VI in November: ‘We have received a large number of internees … dispatched in a great hurry … some real injustices have been committed.'

In early 1941 the British Home Office sent Major Julian Layton to Australia to investigate the situation and assist with possible repatriation. He recommended that the internees should be reclassified as ‘refugee aliens’.

By the end of 1941 most of the internees had been released from detention. Many joined the Australian army’s 8th Employment Company, which engaged manual labour in essential services inside Australia. Others returned to England.

At the end of the war 900 of the original Dunera Boys remained in Australia.

Contribution of the Dunera Boys

The Dunera Boys who stayed on in Australia made huge contributions to the cultural, academic and economic life of the country. Among them were men who went on to become nationally and internationally recognised, including:

- artists Ludwig Hirshfield Mack and Heinz Henghes

- athletic coach Franz Stampfl

- composers Felix Werder and his father Boaz Bischofswerder

- economist Fred Gruen

- engineer Paul Eisenklam

- furniture designers Fred Lowen and Ernst Rodeck

- philosophers Kurt Baier and Gerd Buchdahl

- photographers Hans Axel and Henry Talbot

- physicist Hans Buchdahl.

The influence of that one ship of poorly treated refugees on Australia was immense.

References

Paul Bartrop and Gabrielle Eisen, The Dunera Affair: A Documentary Resource Book, The Jewish Museum of Australia and Schwartz and Wilkinson, Victoria, 1990.

Sue Everett, Not Welcome: A Dunera Boy’s Escape from Nazi Oppression to Freedom in Australia, Hybrid Publishers, Melbourne, 2010.

Cyril Pearl, The Dunera Scandal, Mandarin Australia, Sydney, 1990.