Australian scientists used dogs in Antarctica from the early 1950s until 1993. They were withdrawn in December 1993 to comply with an international agreement to protect Antarctica from introduced species.

Ros Kelly, Minister for the Environment, 6 June 1996:

There was really no alternative action for us to have taken. If we had not agreed to bring the dogs out, the whole negotiation process for the Madrid Protocol would have collapsed.

First Australian dogs in the Antarctic

In 1949 a French expedition to the Antarctic had to turn back to Australia. The expedition’s Labrador and Greenland huskies were placed in quarantine at Melbourne Zoo.

Australia purchased some of these dogs, as well as pups born at the zoo. Next year they were sent to Heard Island, a volcanic island 1500 kilometres north of Antarctica, where Australia had recently set up a base.

From 1954 some of the Heard Island dogs moved on to the Australian Mawson, Davis and Wilkes bases in Antarctica itself.

One dog born on Heard Island, Oscar, fathered over 50 pups before he died in a blizzard in 1962. To reduce the problem of inbreeding, new dogs were brought in, including Alaskan malamutes from an American base.

Sledge dogs in Antarctica

Dogs had a long history in Antarctica. In 1911 the first team to reach the South Pole, led by Roald Amundsen, used dog sleds to make a speedy dash to the Pole. But few of Amundsen’s dogs survived. Most died from the conditions or became food for the men and the remaining dogs.

Explorers and scientists in Antarctica needed to carry supplies and equipment over great distances. They used sledges, pulled by dogs, ponies or the men themselves. Dogs handled the conditions much better than ponies, and took the load off the men.

Nevertheless, the work was not easy. ‘Serious dog-sledging is about as hard a bloody thing as you can find to do,’ commented one veteran.

Dogs most commonly worked in teams of nine. There was a lighter, often female, lead dog, and four pairs of dogs behind. They could pull a load of up to 50 kilograms per dog. In good conditions, teams could cover 25 kilometres in a day.

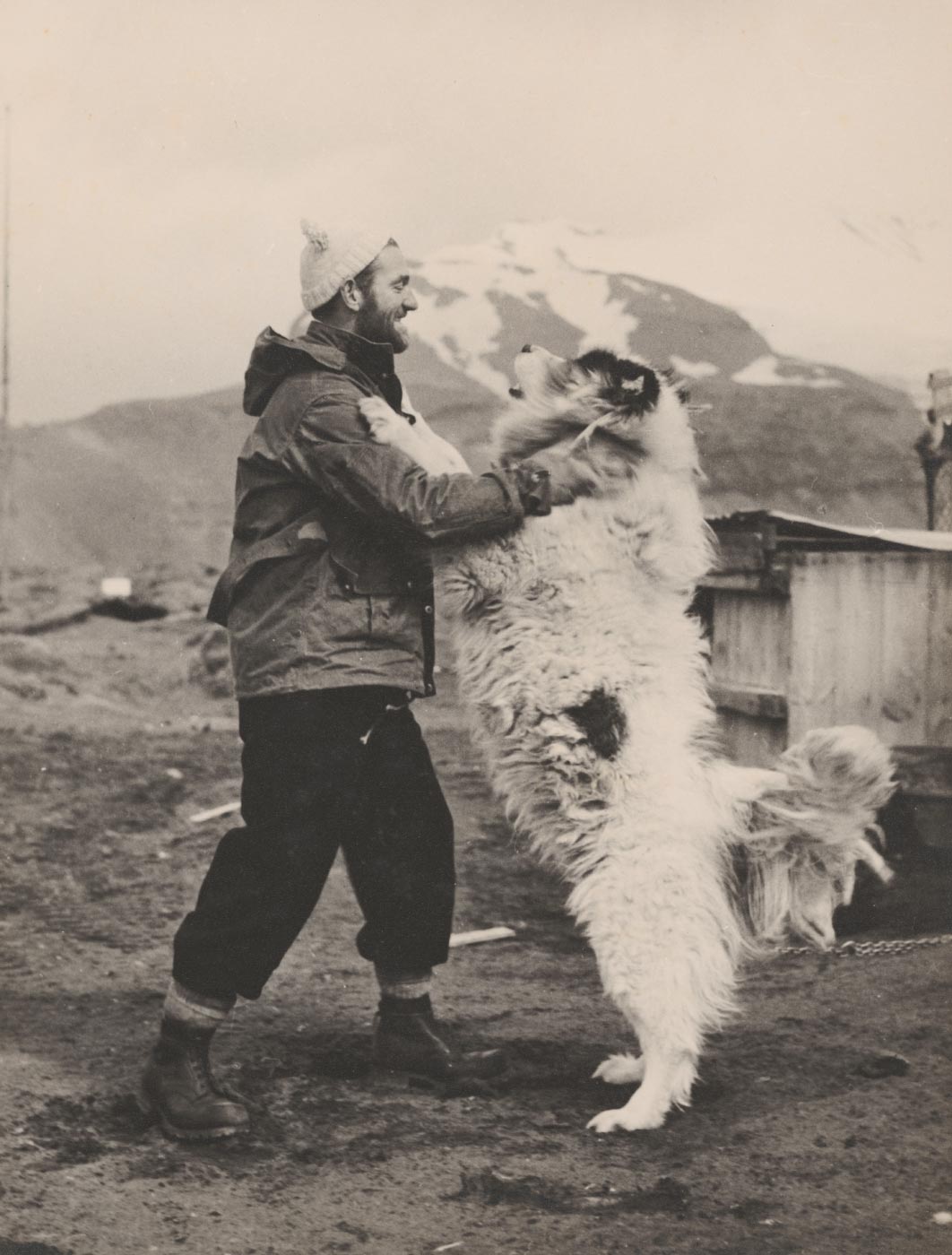

Dog lovers

A British expedition brought the first dogs to Antarctica in 1899.

On that expedition, seven men were trapped in a tent for four days by a blizzard. They brought their dogs into the tent, and the warmth of the dogs’ bodies saved the men’s lives.

For nearly a century men in a harsh environment, especially in winter, also enjoyed the emotional warmth of their dogs.

Even after the introduction of powered tracked vehicles to pull sleds, for a long time dogs were more versatile in difficult terrain. Only in the 1970s did mechanisation on the ground and in the air really make dogs unnecessary.

Nevertheless, several nations kept dogs on at their Antarctic bases, for their companionship and to use for recreational sledging.

The road to expulsion

But the dogs’ days in Antarctica were numbered. In the 1980s the question of whether mining should be allowed in Antarctica became deeply controversial. There was increasing pressure to preserve the relatively pristine Antarctic environment. Australia helped negotiate a convention which would regulate but eventually allow mining.

But then, at the last minute, Australia pulled out. Opposition to the treaty was initially led by Treasurer Paul Keating, largely on environmental grounds.

Greenpeace and other organisations mounted a strong public campaign against signing any convention that would ever allow mining.

Eventually, these forces won over the government, and Australia led a strong – and ultimately successful – campaign to block the minerals convention, whose terms it had itself helped to draft.

With the convention abandoned, the Antarctic treaty partners instead negotiated a Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (known as the Madrid Protocol).

The protocol, eventually adopted in 1991, banned mining, but also banned the introduction of non-native animals to Antarctica. Specifically, it noted, ‘Dogs shall not be introduced onto land, ice shelves or sea ice.'

Environmental problems

During negotiations, Australia had asked for an exemption for its dogs. The other nations, angered by the Australian abandonment of the earlier convention, were not inclined to grant concessions. And Australians themselves were increasingly concerned to protect the Antarctic environment.

A few years earlier, for example, Australia had led the way in bringing rubbish home rather than leaving it in Antarctica. The Australians could not argue for both protection of Antarctica and retention of the dogs: they agreed to bring the dogs home.

Dogs damaged the environment in several ways. Until 1982 animals such as seals were killed to feed them. The dogs were likely to maul penguins which strayed too close to their lines, and they sometimes broke free and attacked other animals. And there were serious fears that they might pass diseases, such as canine distemper, on to the seal population.

Final chapter

Old Antarctica hands waged a spirited, sometimes spiteful campaign against the decision to get rid of their much-loved dogs. But the last Australian dogs left in December 1993, and the last British ones in February 1994. A film, The Last Husky: The Final Journey of Antarctica’s Sledge Dogs, recorded the departure of the Australian dogs.

Despite rumours that they would be put down, most of the Australian dogs went to an outdoor recreation and educational establishment near Ely, Minnesota, in the United States. There they could work out their years in a cold climate.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Tim Bowden, The Silence Calling: Australians in Antarctica 1947–97, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW, 1997.

David Day, Antarctica: A Biography, Random House Australia, North Sydney, NSW, 2012 [reprinted: Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013].