In February 1942, as Singapore fell and the Japanese military prepared to invade Papua New Guinea, the 7th Division of the Second Australian Imperial Force was sailing from the Middle East back to the Pacific.

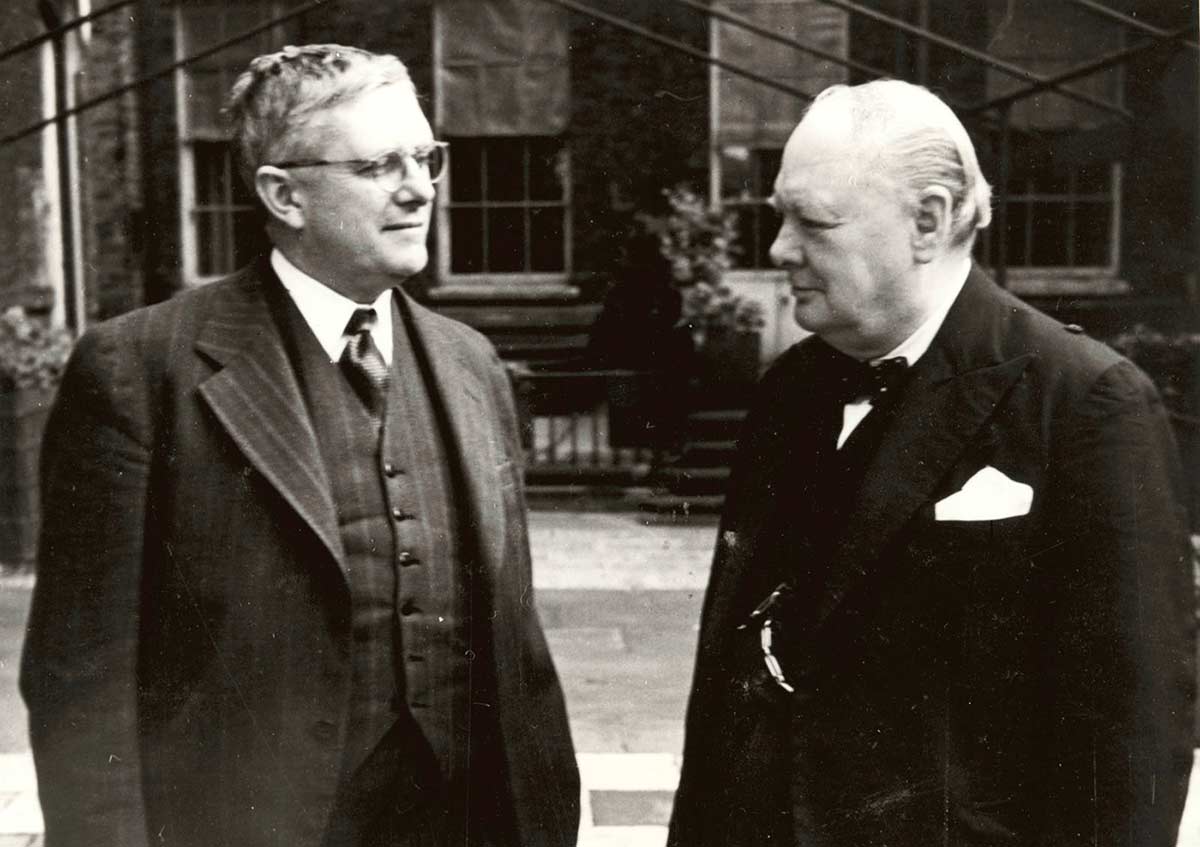

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill insisted the 7th Division should be deployed to Burma while the Australian Prime Minister John Curtin argued they should return immediately to defend Australia.

A diplomatic feud ensued, but Curtin brought the troops home, adding momentum to Australia’s realignment of its foreign policy towards the United States rather than its traditional partner Great Britain.

Winston Churchill to John Curtin, 20 February 1942:

I suppose you realise that your leading division, the head of which is sailing south of Colombo to N.E.I. [Netherlands East Indies, now Indonesia] at this moment in our scanty British and American shipping, is the only force that can reach Rangoon in time to prevent its loss and the severance of communication with China.

Outbreak of the Second World War

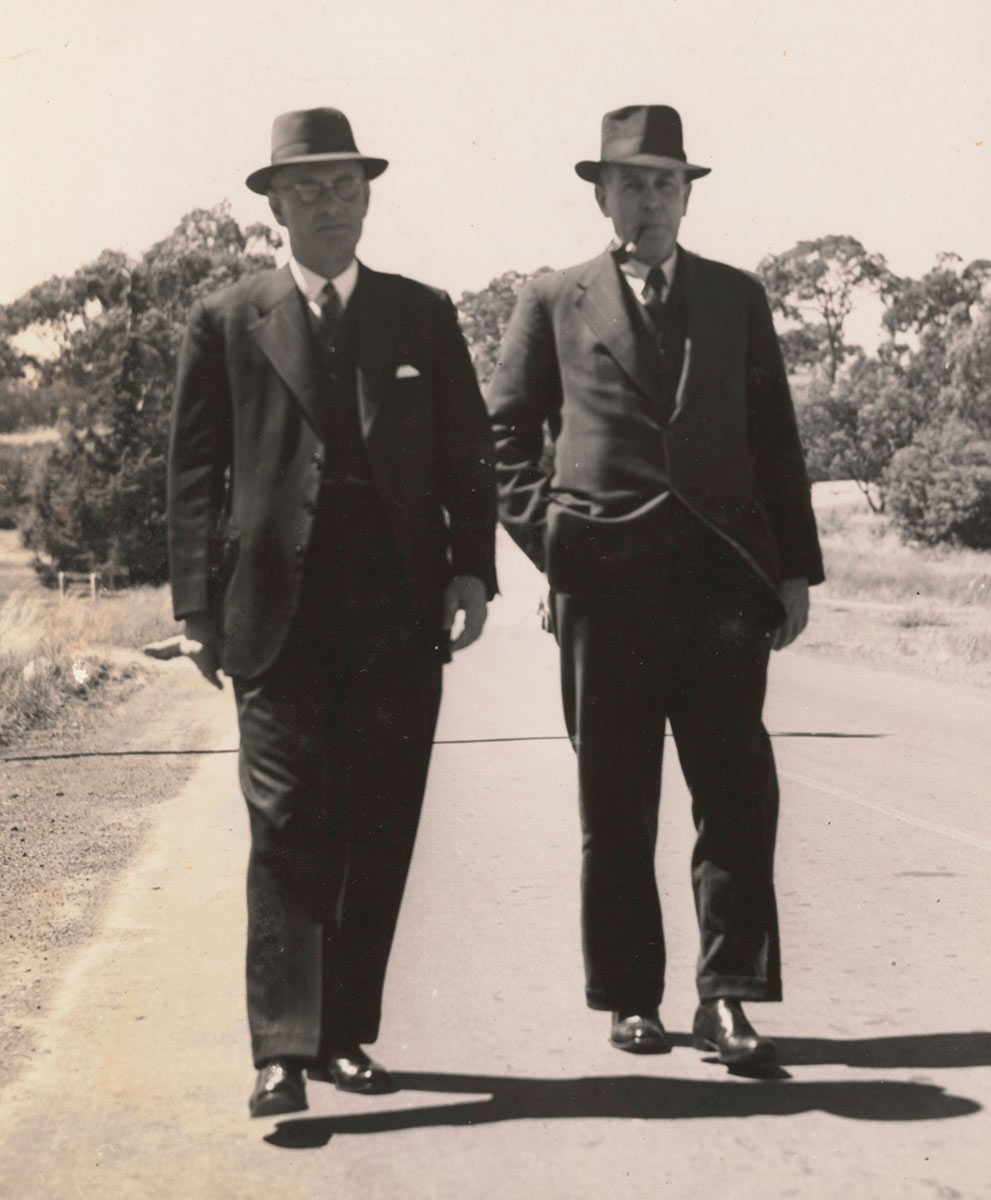

With the death in office of Joseph Lyons on 7 April 1939, Robert Menzies took over as Prime Minister for the United Australia Party (UAP). Menzies declared war on Germany on Australia’s behalf on 3 September 1939.

Menzies identified with and felt great loyalty towards the British Empire, and his declaration of war stated that: ‘Great Britain has declared war upon [Germany] and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.’

The early stages of the Second World War were fought in Europe and the Middle East, and the 20,000-strong volunteer Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) was formed to fight overseas.

The 2nd AIF fought through late 1940 and 1941 in the Western Desert in North Africa, Greece and the Syria–Lebanon campaign.

1940 federal election

The federal election of 21 September 1940 saw the UAP Country Party coalition hold on to power, but only with the help of two independent members of parliament. In October, the independents voted against the coalition’s budget and so brought down the government.

The Governor-General, Lord Gowrie, was reluctant to call another election because of the war and after John Curtin secured support from the independents for a Labor government, he was sworn in as Prime Minister on 7 October 1941.

John Curtin

The new Prime Minister had a background as a socialist union organiser and left wing journalist, and he had worked his way up through the ranks of the Labor Party.

Through the 1920s and 1930s Curtin and the Labor Party had refused to endorse the Singapore strategy whereby Australia supported, financially and militarily, the construction of a large British naval base at Singapore as the primary line of defence against potential Japanese expansion into the South Pacific and South Asia.

Curtin had campaigned during the 1940 election that the ‘primary responsibility of any Australian Government was to ensure the security and integrity of its own soil and people before contributing to a common cause’.

War with Japan

Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on 7 December 1941, which immediately led the United States and Great Britain to declare war on Japan.

The next day Australia declared war on Japan, the first declaration of war Australia had ever made independently of Britain.

In his New Year’s message delivered on the radio on 26 December 1941 and published in the Melbourne Herald the next day, Curtin announced that: ‘Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.’ This decisive move away from Great Britain infuriated British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

On 15 February 1942 Singapore fell to Japanese forces and the defensive strategy that Australia had invested so much into over the previous 15 years was in ruins. A portion of the Australian 8th Division had been part of Singapore’s defences. More than 15,000 of these soldiers were captured, of whom more than 7,000 would die as prisoners of war.

Churchill, Roosevelt and the Chinese Nationalists

In January 1942 the Australian 7th Division was returning from the Middle East. Initially these troops were to be deployed to the Netherlands East Indies, present-day Indonesia, to help British troops create a defensive line against the Japanese advance.

However, the British General Archibald Wavell, in charge of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command, informed Churchill that the East Indies could not be held. At this point Churchill insisted the Australian troops redeploy to Burma.

Churchill was motivated, in part, by a desire to protect India, the ‘Jewel in the Crown’ of the British Empire, but he also wished to keep supply lines open to the Chinese Nationalists who were fighting the Japanese.

This strategy also appealed to US President Franklin D Roosevelt who strongly supported the Chinese Nationalist cause.

Churchill and Roosevelt, unbeknownst to Curtin, had agreed at the Arcadia Conference in December 1941 on a ‘Germany first’ policy whereby the bulk of Allied resources would be directed towards defeating the Axis powers in Europe. Compared to defeating Germany, defending Australia from Japan was of little importance to Britain.

On 17 February 1942, two days after the fall of Singapore, the Pacific War Council (the inter-governmental body controlling the Allied war effort in the Pacific) met.

Earle Page, Australia’s representative, reported to Curtin that: ‘The Australian Government should be asked to agree that the Seventh Australian Division already on the water should go to the most urgent spot at the moment, which is Burma.’

Curtin replied the next day: ‘Government has decided that it cannot agree to the proposal that the 7th AIF Division should be diverted to Burma.’

Curtin and Churchill clash

This led to furious communications between London and Canberra with Curtin emphatically stating on 22 February 1942 that the troops should immediately return to Australia.

Amazingly, Churchill then gave instructions to the British Admiralty, who were transporting the Australian division, to change the course of the troopships and sail for the Burmese capital, Rangoon.

Curtin and his war cabinet were shocked and enraged; Churchill had gone too far. Curtin replied to Churchill the following day, demanding that the soldiers be returned to Australia immediately. Churchill conceded, the ships changed course again and continued on to Australia.

This was a time of intense stress for Curtin as the troop ships were vulnerable to Japanese attack. However, the soldiers arrived safely in Adelaide on 23 and 27 March 1942.

On 14 March, Curtin had given a radio address to the people of the United States urging Americans to stand with Australia against the Japanese, saying: ‘Australia is the last bastion between the west coast of America and the Japanese. If Australia goes, the Americas are wide open.’

Curtin’s foreign policy decision

Curtin’s decision that the Australian troops should be returned home proved correct. The Australian soldiers would have arrived in Rangoon on 26 February 1942, by which time the Japanese were already in position to take the city.

Rangoon fell on 7 March, the same day Japanese forces invaded Lae and Salamaua and initiated the New Guinea campaign to the immediate north of Australia.

Soldiers from the 7th Division were essential in turning the tide against the Japanese advance, fighting in the first battles that halted the Japanese progress in the Pacific at Milne Bay and on the protracted and bloody Kokoda Trail campaign.

Curtin’s insistence on returning troops to Australia rather than fighting in a distant part of the British Empire combined with his New Year’s speech in December 1941 and his American address in March 1942 were instrumental in moving Australia’s primary foreign policy allegiances from Britain to the United States.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Lesley Carmen-Brown and Geraldine Ditchburn (eds), John Curtin and International Relations during World War II, John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library, Perth, Western Australia, 1999.

David Day, John Curtin, Harper Collins, Sydney, 1999.

John K Edwards, Curtin’s Gift: Reinterpreting Australia’s Greatest Prime Minister, Allen and Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2005.

Graham Freudenberg, Churchill and Australia, Pan MacMillan, Sydney, 2008.