The establishment of the CSIRO began with the temporary Advisory Council of Science and Industry in 1916.

Underfunded and lacking support from the states, the council struggled until 1920 when it became a permanent body coordinating agricultural research across Australia.

Only in 1926 did it start undertaking its own research. The final stage of its emergence came in 1949 when it became the CSIRO, an organisation that has made a wide range of scientific breakthroughs.

Prime Minister Billy Hughes, 1916:

Science can make rural industries commercially profitable, making the desert bloom like a rose; it can make rural life pleasant as well as profitable … Science will lead the manufacturer into green pastures by solving for him problems that seemed to him insoluble. It will open up a thousand new avenues for capital and labour.

Early scientific research in Australia

Throughout the 19th century, Australia’s main exports were wheat, wool and gold.

However, towards the end of the century Australian agriculture was facing major problems, including drought and diminishing crop yields, that were only partly offset by the development of improved seeds and farming technology.

With the best land occupied, the wheat industry had to expand into territory where poor soils yielded poor crops.

The agricultural industry also faced the threat of disease in the form of stem rust, which was only addressed in the 1890s by William Farrer, an employee of the NSW Department of Agriculture.

Most colonies had established agricultural departments by the 1880s. They were soon among the largest government agencies. The federal government tried to establish a similar department in 1909 and 1913, but on both occasions the legislation necessary failed to pass through parliament.

Up until the outbreak of the First World War, all significant scientific research in Australia was agricultural in nature and carried out by the states.

Hughes and Hagelthorn

In 1915 Prime Minister Billy Hughes became passionate about creating a national scientific research body that would focus on improving Australia’s agricultural and manufacturing sectors.

Hughes realised that Australia’s industrial methods were inferior to most other developed countries, and that a nation so dependent on agriculture needed to conduct its own centrally coordinated research.

Hughes knew that to create such a body would require the support of the states. Fortunately, Frederick Hagelthorn, the Victorian Minister for Agriculture, shared his vision, and by December 1915 had managed to garner the support of other state agriculture ministers.

Hagelthorn argued that a federal body would prevent duplication of work among the various state departments, and that the agricultural problems Australia faced existed on a national scale.

Advisory Council of Science and Industry

In January 1916 Hughes called together prominent scientists and industrialists. This resulted in the establishment of a temporary Advisory Council of Science and Industry, whose task was to develop a plan for the establishment of the research body itself.

The council had an executive committee of three academics and three staff, who worked in loaned government premises in East Melbourne. In its first year it received only £541 in funding.

In 1916 the council produced a start-up plan, but at this crucial stage state and federal political support failed. The council struggled on for the next three years, appointing expert committees which coordinated and stimulated research in existing laboratories around Australia.

In 1920 an Act of federal parliament made the small organisation permanent, and it was renamed the Institute of Science and Industry. However, it still suffered from underfunding. The new institute devoted itself to coordinating primary industry research work, mainly in forestry.

One of its achievements during this lean period was the coordination of research that led to the eradication of prickly pear, an invasive weed which was spreading over millions of hectares of agricultural land.

Council for Scientific and Industrial Research

In 1925 Prime Minister Stanley Bruce convened a conference to advise how the Institute of Science and Industry might be reformed and given a clearer role.

Bruce recruited Sir Frank Heath, an eminent British scientific administrator, to advise on national scientific research in Australia.

The following year, parliament passed legislation creating the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). This body was much better funded than its predecessors. With its central executive committee and various state advisory committees it was seen as a triumph of collaborative federalism.

Still, the CSIR had only 41 scientific staff housed in a few rooms rented from the technical college in the Melbourne suburb of Brunswick. But for the first time, it began to conduct its own research.

Its exact role was still a source of controversy. Certain elements of the scientific community argued that it would create more duplication of research rather than less. In 1927 a federal–state accord resolved that the CSIR’s role would be long-term and national, while its state counterparts would be short-term and regional.

Importantly, it had more independence from the government than its predecessors. Its chief executive officer was Sir David Rivett, whose vision and leadership shaped the CSIR over the next 20 years. He sought to strike a balance between working on immediate problems with existing scientific knowledge and expanding that knowledge with pure research.

Rivett was also instrumental in securing sufficient government funding despite the onset of the Depression.

In the years leading up to the Second World War, the CSIR focused on the huge range of problems in Australian agriculture – still the nation’s chief source of income.

These problems included sheep and cattle diseases, the spread of rabbits and insect pests that afflicted crops. CSIR’s achievements in these areas gave it credibility within the agricultural sector and the public more broadly.

From 1936, it also began work on addressing the problems faced by Australia’s gradually improving, post-Depression manufacturing industry. During the Second World War new focuses included the development of portable radar sets and of a highly effective mosquito repellent for use by troops in the Pacific theatre (later marketed as Aerogard).

CSIRO

In 1949 the legislation that established the CSIR was amended to create the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). This came about because the government believed that a largely civilian research body should not be doing classified defence research, as had occurred during and after the Second World War.

Despite losing this aspect of its work, the reconstitution of the organisation gave it even greater independence and led to a huge expansion in the amount and nature of the work it did. It now placed a greater emphasis on fields such as manufacturing technology, mineral research, environmental conservation, meteorology and radioastronomy.

One of the CSIRO’s most famous achievements was controlling the rabbit plague by successfully – even if controversially – introducing the virus myxomatosis in 1950.

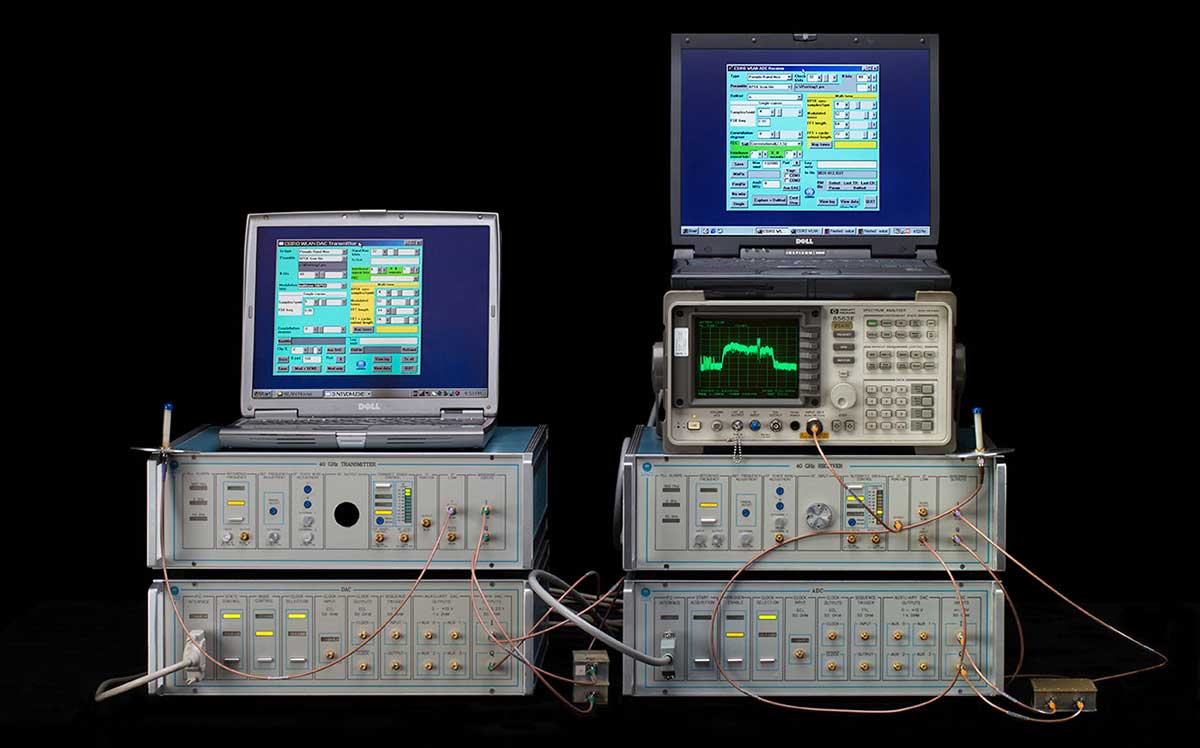

It has also been responsible for Australia’s first computer (1949), plastic banknotes (developed in 1978 but only introduced from 1988), the technology that led to the development of wi-fi (1996) and many other breakthroughs.

Explore defining moments

References

CSIRO in Brief, CSIRO Central Communication Unit, Canberra, 1977.

George Currie and John Graham, The Origins of CSIRO: Science and the Commonwealth Government, 1901–1926, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 1966.

Peter Ewer (ed.), For the Common Good: CSIRO and Public Sector Research and Development, Pluto Press Australia, Leichhardt, NSW, 1995.

CB Schedvin, Shaping Science and Industry: A History of Australia’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, 1926–49, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1987.