Coranderrk was established as a reserve for the Aboriginal people of south-central Victoria, operated under Australia’s first administrative framework to ‘manage’ Aboriginal affairs, an approach later adopted throughout the country.

Coranderrk’s residents fought against efforts to control their lives. Their sustained resistance is often cited as among the first Indigenous campaigns for land rights and self-determination.

William Barak, statement to the Victorian Parliamentary Coranderrk Inquiry, 1881:

And we don’t want any Board nor inspecting Capt. Page over us – only one man, that is Mr. Green, and the station to be under the Chief Secretary; and then we will show to the country that we can work it and make it pay, and I know it will.

Victorian Aboriginal population devastated

The Indigenous population of Victoria was estimated to be at least 11,500 before the founding of Melbourne in 1835.

Less than 30 years later frontier violence and the introduction of European diseases had decimated the population and only about 2,000 Aboriginal people survived. Europeans thought Aboriginal people were a dying race.

Social reformers in Britain, alarmed about the devastation of Indigenous populations throughout the empire, prompted an investigation by the Parliamentary Select Committee on Aboriginal Tribes (British Settlements).

The resulting ‘Buxton Report’ of 1837, recommended the enactment of special laws to protect Indigenous people.

Development of protection policies

The New South Wales colonial government’s response to the report was to establish the Port Phillip Protectorate in 1838 with five officials appointed to advocate for Indigenous people’s interests in conflicts with European settlers. Underfunded and subject to political interference, it was disbanded in 1849.

In January 1859 the Victorian Select Committee recommended reserving large tracts of land for Aboriginal people to protect them from European predations and diseases. Many settlers, whose population had grown significantly in Victoria since the discovery of gold, opposed setting aside productive land for Indigenous people.

In 1860 the Central Board Appointed to Watch Over the Interests of the Aborigines was established and made responsible for:

- taking a census of the Aboriginal population

- providing food and clothing

- directing the administration of Aboriginal reserves and stations.

Indigenous affairs was further regulated in 1869 with the passing of the Aborigines Protection Act, which replaced the Central Board with the Board for the Protection of the Aborigines. The board had power over many aspects of Indigenous peoples’ lives including where they could live and work.

This administrative system was the first of its kind in the Australian colonies, establishing a standard of management later adopted throughout the nation.

Establishment of Coranderrk

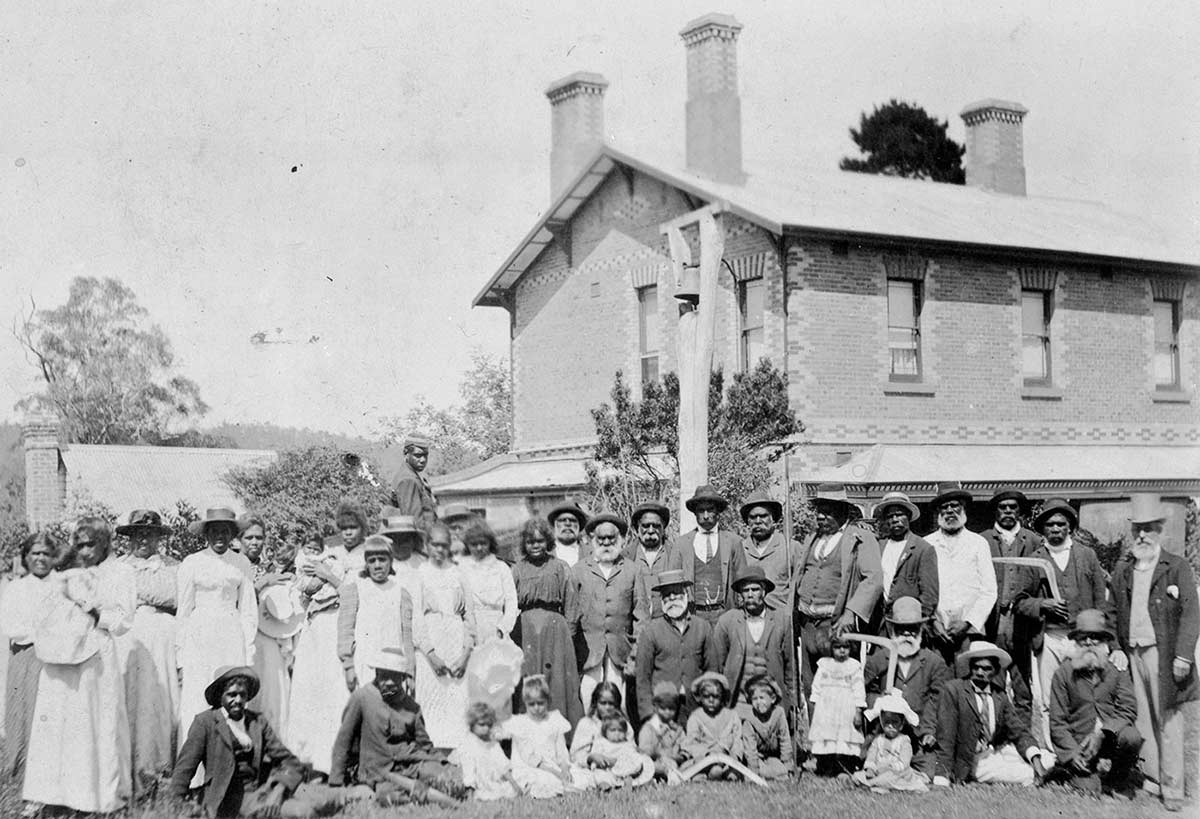

In early 1863 about 40 people from several Kulin clans walked over the Dandenong Ranges, to Coranderrk.

Three years earlier, settlers had driven them from a site by the Acheron River to a location on the Mohican pastoral run, which they were forced to abandon because of its cold climate.

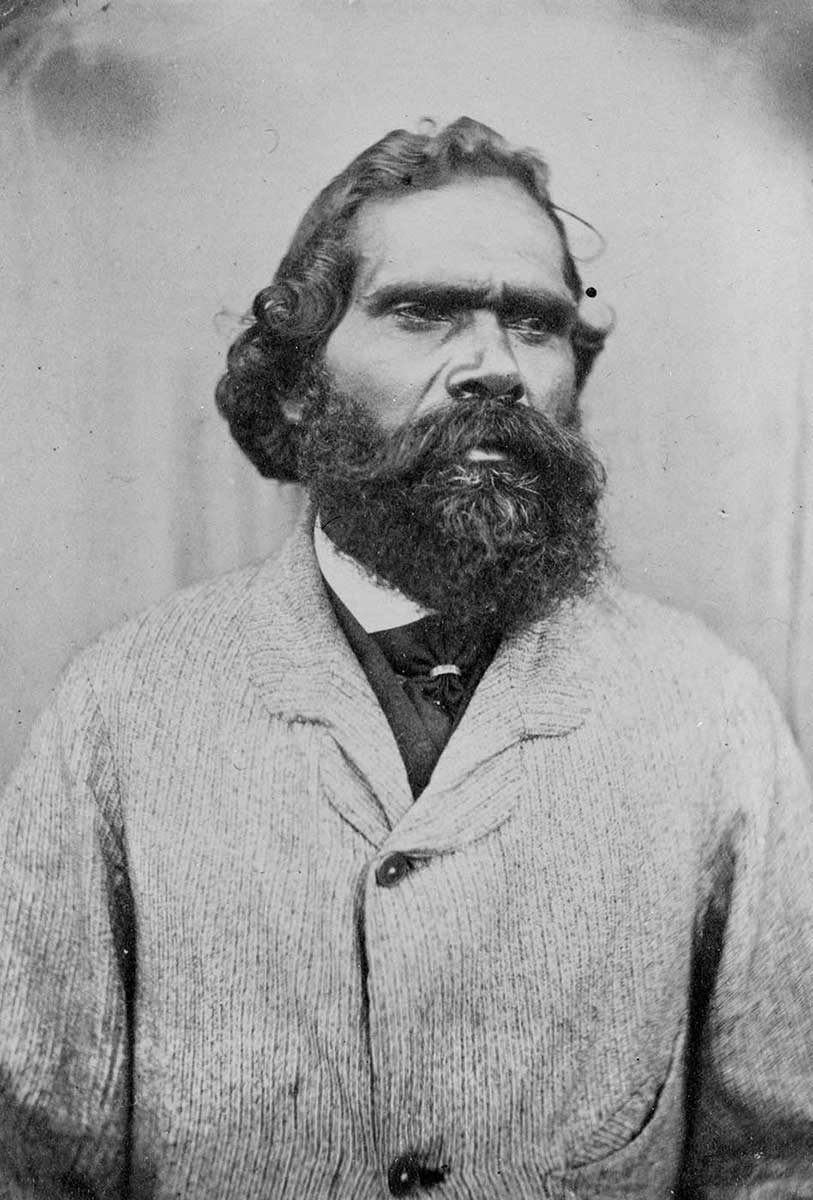

Clan leaders Simon Wonga and William Barak with John Green, the government appointed inspector and manager at the Mohican site, led the group to a traditional camp at the junction of the Yarra River and Badger Creek.

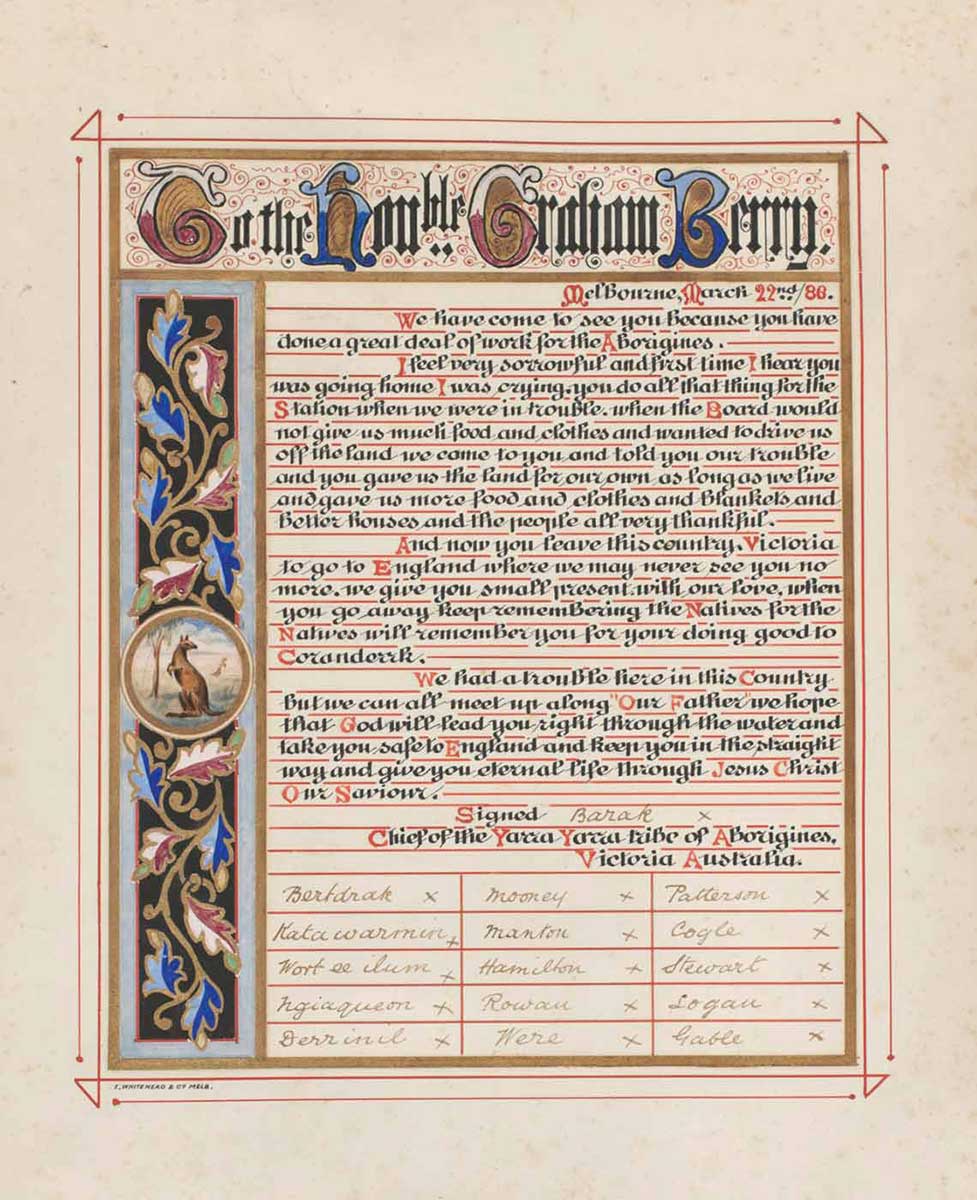

In May 1863 Barak and Wonga led a deputation to Melbourne to present an address to Governor Sir Henry Barkly about their need for a permanent homeland. It was the first of many delegations by Kulin leaders from Coranderrk.

In June 1863, 2300 acres were gazetted as a reserve for Coranderrk Aboriginal Station. Indigenous testimony shows that Coranderrk was productive and profitable in its early years.

Green’s management supported the Kulin peoples’ autonomy in developing the station and was respectful of Indigenous traditions. Residents' literacy increased and a better diet led to improved health.

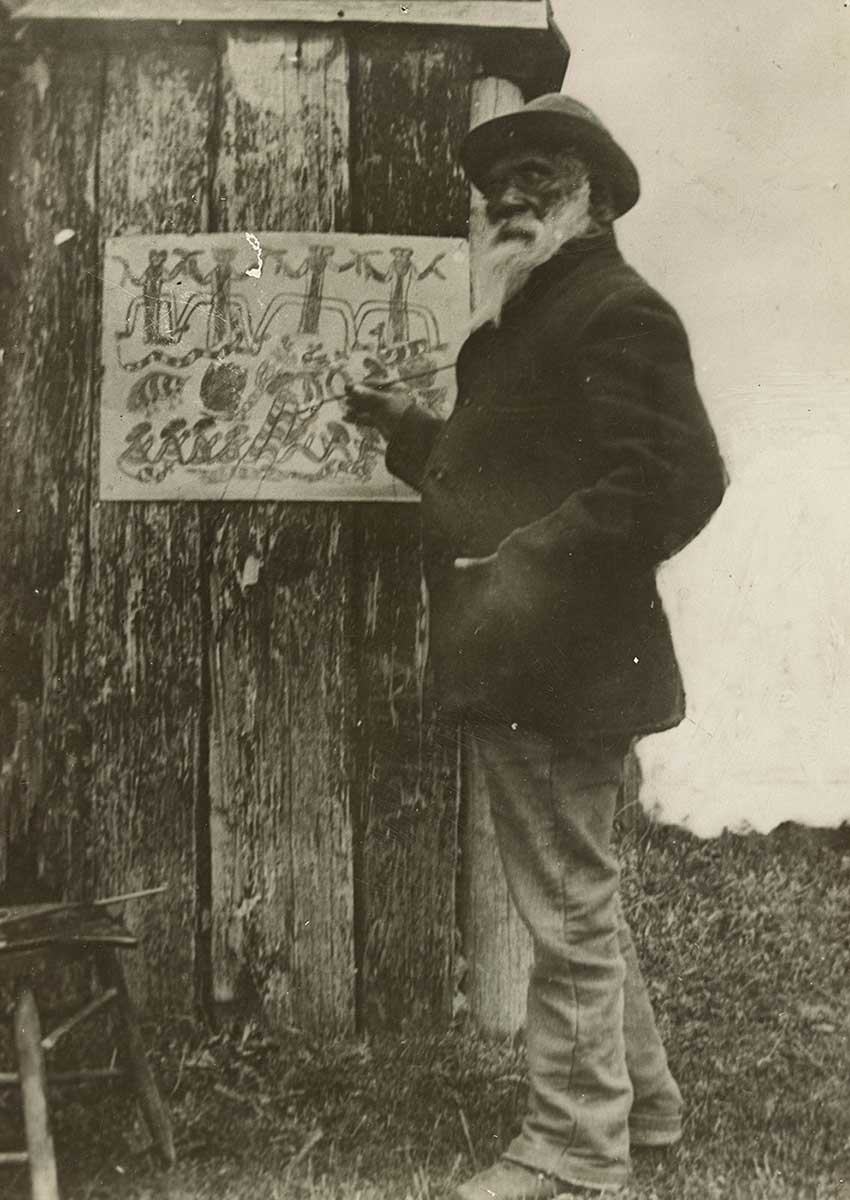

Coranderrk was a popular tourist destination and the sale of baskets, bags, boomerangs and skin rugs, made by women and elderly men, contributed significantly to the station's income. Coranderrk’s woven goods, which were particularly admired, were stocked by a Collins Street shop in 1869.

Mismanagement

From 1872, some board members who disapproved of Green’s view that the Kulin people should run the station, worked to undermine his authority. Green’s resignation in 1874 was a turning point for the Coranderrk community.

Subsequent European managers, acting in accordance with the board’s direction and the paternalistic view of Indigenous people as ‘child-like’, were authoritarian. They disciplined individuals and directed every day life.

Food supplies were cut and residents could only obtain meat if they went into debt to the local butcher. Incompetent and uncaring administration led to derelict housing, inadequate medical attention and a lack of warm clothing for residents.

Resistance and protest

As living conditions at Coranderrk deteriorated, the community protested.

William Barak, Thomas Bamfield, Robert Wandin and others led many delegations along the 67-kilometre walk from Coranderrk to Melbourne to deliver written petitions and to talk to politicians and officials.

Conditions at Coranderrk in the 1870s and 1880s became a progressive cause in Melbourne society. Barak and Bamfield were particularly adept at working with European allies, like politician Graham Berry and philanthropist Anne Bon, to bring the demands of Coranderrk residents to public attention.

Coranderrk became the subject of many newspaper articles and questions in parliament. Management of the reserve was investigated as part of the 1877 Royal Commission on the Aborigines.

At a parliamentary inquiry in 1881 Kulin leaders and individuals were called to testify.

Absorption policy at Coranderrk

In 1886 the Victorian Government adopted a new policy to regulate the lives of Indigenous people under the Aboriginal Protection Law Amendment Act, commonly known as the ‘Half-Caste Act’.

The law required that Aboriginal people with European ancestry aged between 15 and 35 leave reserves such as Coranderrk to undertake employment and ‘absorption’ into the general white community. While a deputation of Coranderrk leaders protested against the proposed law, they could not prevent its adoption.

The law struck at the very identity of the Kulin people. It had a devastating impact on the community at Coranderrk and other Aboriginal stations, halving resident populations and splitting families.

Jemima Donelly wrote to Board for the Protection of the Aborigines Secretary, William J Ditchburn, on 16 December 1913 asking, ‘for permission for my three sons to stay with me at Coranderrk through the Christmas Holidays for a fortnight. kindly oblige …’

Coranderrk closes

Despite their efforts, the Coranderrk community could not overcome overwhelming pressure from settlers and developers to sell or lease portions of Coranderrk. Pressure intensified as the implementation of the ‘Half-Caste Act' reduced the number of Kulin people at Coranderrk to 31 by 1893.

Coranderrk was officially closed as an Aboriginal station in 1924. From the 1890s portions had been carved off the holding, acres leased and an illegal road built. The last Kulin resident died in 1944.

In 1948 the remaining reserve was divided up for soldier settlement.

Coranderrk returned

In 1991 Coranderrk cemetery was handed back to the Wurundjeri people. Over the next decade, an additional 119 hectares of Coranderrk was acquired by the Kulin people.

In our collection

Explore defining moments

References

Aboriginal societies: The experience of contact, Australian Law Reform Commission

Beyond Coranderrk, Public Record Office Victoria

Minutes of evidence project – 1881 Victorian Parliamentary Coranderrk Inquiry

Diane Barwick, Rebellion at Coranderrk, Aboriginal History Inc., Melbourne, 1998.

Ian Clark, A Peep at the Blacks: A History of Tourism at Coranderrk Aboriginal Station, 1863–1924, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2015.

Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw (eds), Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867–1926, University of Melbourne, Victoria, 2002.