Between 1788 and 1868 more than 162,000 convicts were transported to Australia. Of these, about 7,000 arrived in 1833 alone.

The convicts were transported as punishment for crimes committed in Britain and Ireland. In Australia their lives were hard as they helped build the young colony. When they had served their sentences, most stayed on and some became successful settlers.

Letter from the Reverend Richard Johnson, Sydney, 29 July 1794:

A great number of those whose terms have expired have turned settlers, some of whom are doing well, better than many farmers in England.

Why transportation

Transportation as a form of criminal punishment emerged in the British legal system from the early 17th century as an alternative to execution.

Many crimes that today would be considered minor offences were punishable by hanging, and there were 225 identified capital offences at the time.

The American colonies were the main destination for convict transportation in the 18th century and a thriving business developed around the process.

British businessmen obtained contracts for transportation from local sheriffs. They selected the convicts they wanted (usually based on their ability to work) and, once the transport ships arrived in the colonies, sold on the convicts’ labour for the duration of their sentences.

Transportation Act

Prior to 1717 the legal processes behind transportation were obscure, as transportation itself was not a sentence but could be organised by indirect means.

The Transportation Act 1717 simplified and legitimised the process: convicts guilty of capital crimes but commuted by the king would receive 14 years transportation while those convicted of non-capital offences could receive seven years. Returning to England before the sentence was complete was a capital offence in itself.

America

The Act made transportation simpler and increased the number of convicts transported to America. More than 50,000 criminals had been transported by 1775. These convicts were instrumental in the early development of what became the United States of America.

But the American colonies’ unofficial function as a penal colony came to an abrupt halt with the American Revolutionary War. With independence, America stopped accepting convicts from Britain.

Australian solution

Transportation from Britain ceased from 1776 to 1788 and the rapidly growing prison population was housed on ship hulks anchored in rivers and along the sheltered coastline of southern England. The hulks quickly became disease-ridden, with one third of the prisoners dying while on board.

The government investigated transporting convicts to Africa and the Caribbean but neither destination was deemed suitable.

In 1783 James Matra, who had been a junior officer on James Cook’s 1768 voyage to the Pacific and therefore one of the few Europeans to have seen the continent of Australia, proposed to the British Government that Botany Bay was a suitable location for a colony. Joseph Banks, a friend of Matra’s from the 1768 voyage, vigorously supported the proposal.

Initially, the plan was for the colony to be an asylum for British loyalists who wanted to leave the newly independent America, but after a meeting with Home Secretary Lord Sydney, the scheme was reformulated to comprise mostly convicts instead.

In 1785 Orders in Council were issued by the British Government for the creation of a penal colony in New South Wales.

First Fleet

On 12 October 1786 Royal Navy Captain Arthur Phillip was appointed the first governor of New South Wales and immediately began planning the formation of the First Fleet. Phillip drafted a detailed outline of his plans for the new colony including:

The laws of this country will of course be introduced in New South Wales, and there is one that I would wish to take place from the moment His Majesty's forces take possession of the country: That there can be no slavery in a free land, and consequently no slaves.

Phillip was an enlightened leader for his time and imagined the colony not just as a British outpost in the South Pacific, but as a place for convicts to rehabilitate themselves.

On 13 May 1787 the First Fleet sailed from Portsmouth and arrived in Botany Bay on 18 January 1788.

Within a week the fleet left the bay as Phillip decided it was unsuitable for the establishment of a colony. They sailed north to Sydney Cove, now Circular Quay, where the 751 convicts and 252 marines and administrators disembarked. It was there that Phillip established the settlement.

Convicts and the establishment of New South Wales

Governor Phillip instituted a system where convicts were employed according to their skills.

Convicts provided the labour that built the young colony’s roads, bridges and public buildings, but free settlers could also petition the government to assign convicts to work on their farms.

The first free settlers arrived in New South Wales in 1793 but convicts remained in the majority until the great influx of people lured by the gold rushes of the 1850s.

Convict crimes

Convicts were mainly from England and Wales, with a large contingent of Irish (24 per cent) and a much smaller number of Scots (five per cent). Most were sentenced in the rapidly growing cities of Britain, where displaced rural populations struggled to find work in an increasingly industrialised world. Rates of theft increased as people stole food and clothing to survive.

A conviction for robbery of these small items could result in transportation for seven years. About 20 per cent of those convicted were female.

A small proportion of convicts were political prisoners, including Irish home rule insurgents, the unionist Tolpuddle Martyrs, anti-industrialising Luddites, Canadian rebels and political reforming Chartists.

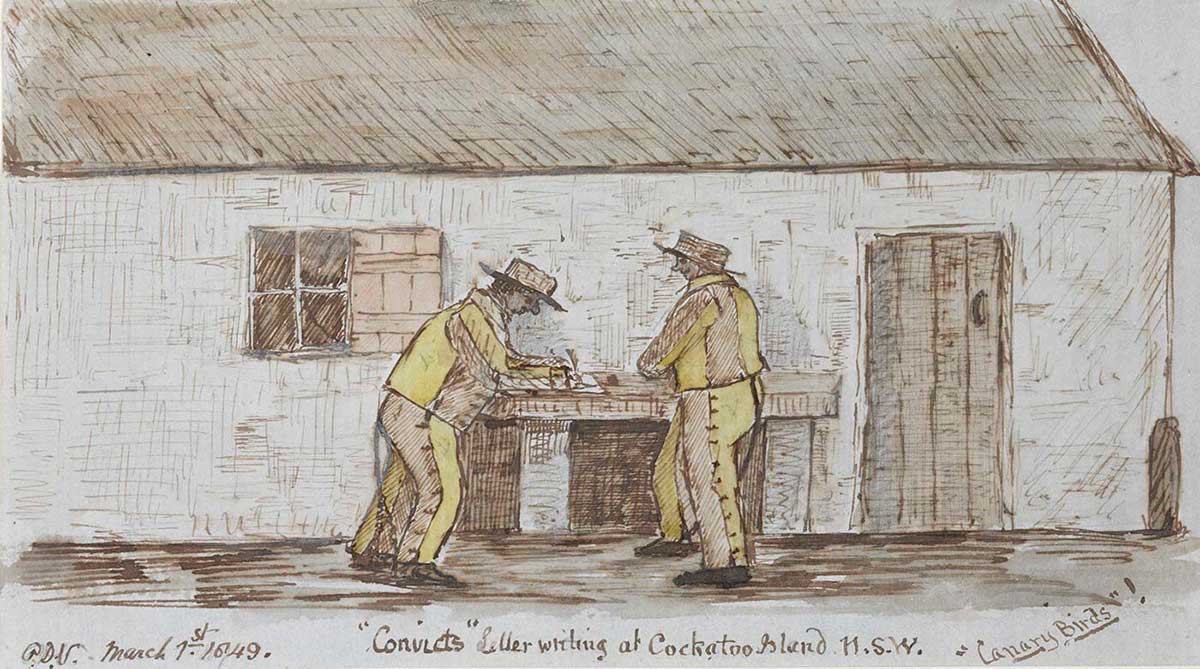

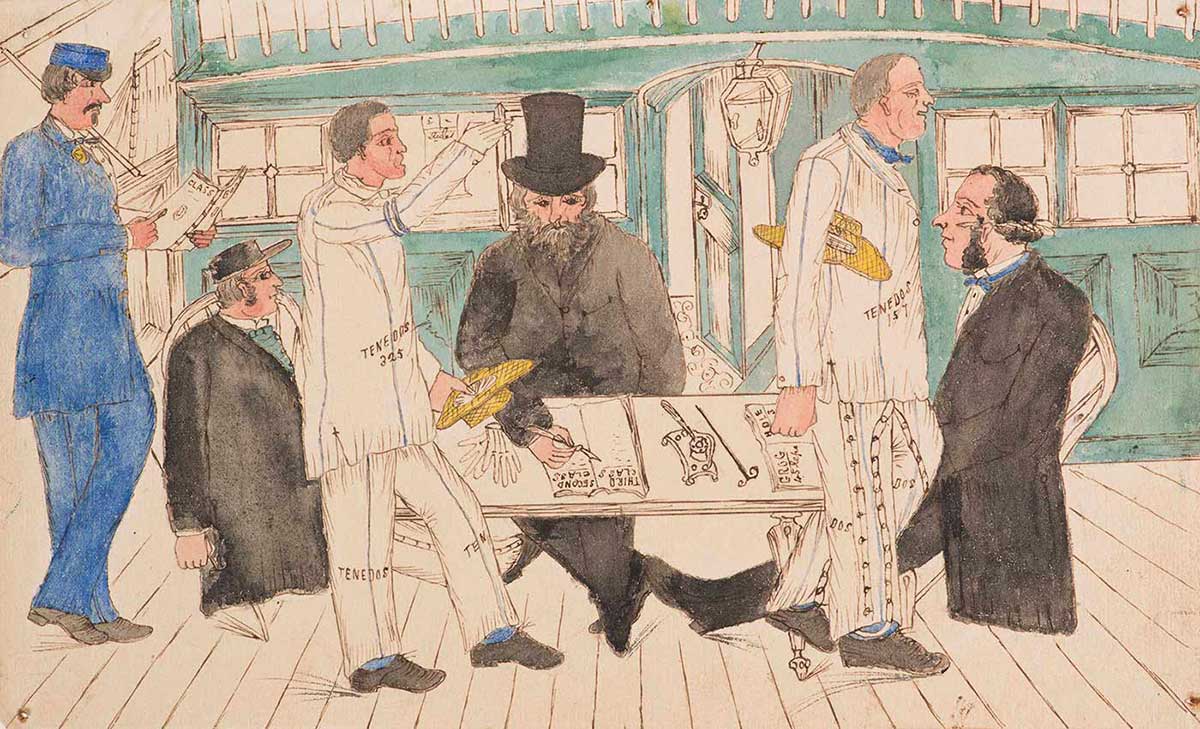

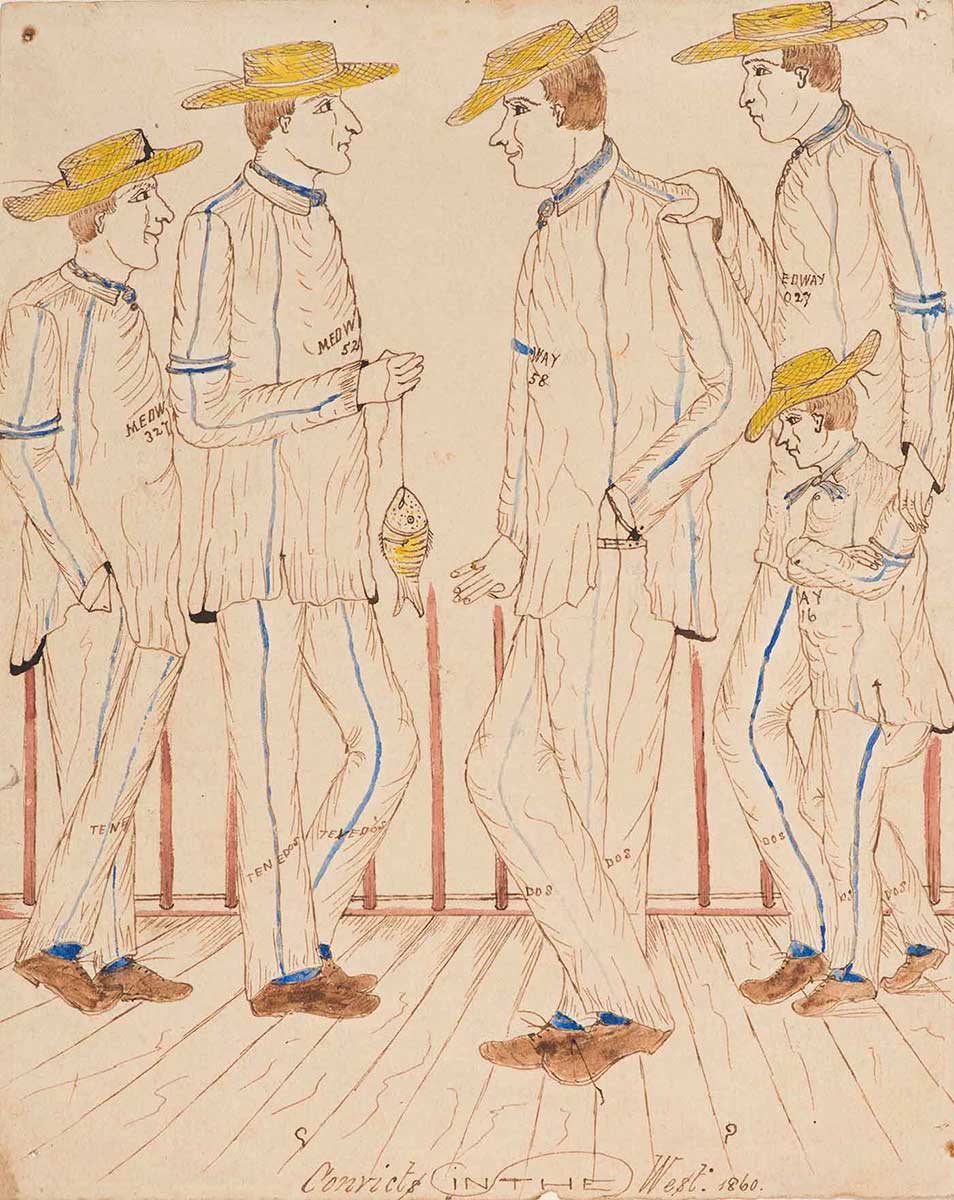

Convict life in Australia

Convicts were sent to Australia to work. Their sentences stipulated they would work from sunrise to sunset, Monday to Saturday. This was their punishment but the colonial administration also viewed it as an opportunity for redemption, as Governor Phillip believed that ‘honest sweat’ was the convict’s best chance of improvement.

Convicts lived under very strict rules and any breaking of those regulations could result in punishment such as whippings, the wearing of leg-irons or solitary confinement. Serious crimes could result in sentences to hard-labour prisons such as Port Arthur or Norfolk Island.

By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.

The majority of convicts stayed on in Australia after their sentences were served. Once free, they could own land and, under Governor Lachlan Macquarie (1810–21), some were appointed to key positions in the colonial government.

Convict transport peaks

In 1833 convict transportation peaked when 7,000 prisoners arrived in Australia but, by this time, public support for the system was already in decline.

However, it wasn’t until 1868 that convict transportation to Australia came to an end.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

You may also like

References

Arthur Phillip, Australia Dictionary of Biography online

Michael Bogle, Convicts: Transportation and Australia, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney, 2008.

John Hirst, Freedom on the Fatal Shore: Australia’s First Colony, Black Inc. Melbourne, 2008.

Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore: A History of the Transportation of Convicts to Australia, 1787–1868, Harvill, London, 1996.