The 1916 and 1917 conscription referendums were among the most divisive moments in Australian history.

Throughout 1916 Australia had experienced problems meeting the troop supply commitments it had made to the British Government. Prime Minister Billy Hughes believed the only way to achieve the numbers needed was through the controversial approach of conscription.

A referendum to determine public support for conscription was held in October 1916 where it failed by a slim margin; a second took place in December 1917 and again most Australians voted against it.

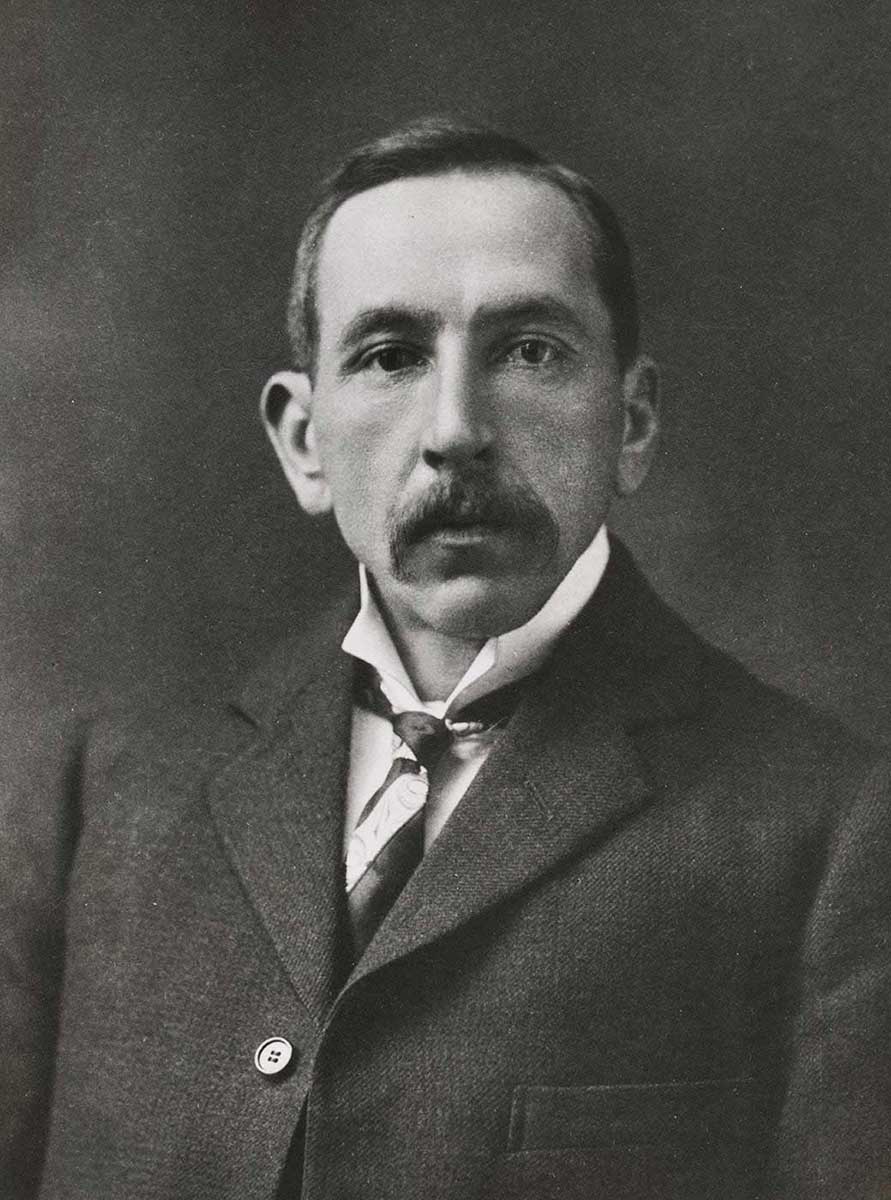

Prime Minister William (Billy) Hughes, 30 August 1916:

To falter now is to make the great sacrifice of lives to no avail, to enable the enemy to recover himself, and, if not to defeat us, to prolong the struggle indefinitely, and thus rob the world of all hope of a lasting peace … Our national existence, our liberties, are at stake. There rests upon every man an obligation to do his duty in the spirit that befits free men.

Prewar compulsory service

The Defence Act of 1903, which provided for the raising and servicing of the new Australian army, was one of the first pieces of legislation passed by the new Commonwealth Government.

One of the provisions of the Act was the government’s right to conscript men for the purpose of self-defence.

In 1909 at the invitation of Prime Minister Alfred Deakin, Field Marshal Kitchener of Great Britain visited Australia to inspect the defence preparedness of the young nation.

In February the following year he submitted a report that recommended the introduction of compulsory military training within Australia. From 1911, males between the ages of 12 and 60 had to enrol in the scheme.

Australia goes to war

On 5 August 1914 Australia joined other countries in the British Empire and declared war on Germany. Men quickly enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), which was to fight alongside the British Army.

Unlike the major European military forces, the AIF was entirely a volunteer army as compulsory military service was still limited to service inside Australia. Official recruitment began in August with the government initially committing 20,000 troops to the campaign.

By the end of the year, more than 50,000 men had enlisted at a rate of nearly 10,000 per month. Men were enlisting for a number of reasons: patriotism, the excitement of action, travel, and for the pay, which was among the most generous of any Allied army. This pay was particularly attractive as Australia was in the midst of a drought and depression.

However, after news of the disastrous Gallipoli campaign made its way back to Australia, enlistments started to decline.

Billy Hughes and the Somme

William (Billy) Hughes replaced Labor Prime Minister Andrew Fisher who resigned on 27 October 1915. Hughes had publicly stated in July 1915 that he would ‘in no circumstances … send men out of the country to fight against their will’.

However, in February 1916 Hughes travelled to Europe to consult with British and European governments on Australia’s contribution to the war effort. Just before he left, the British parliament passed conscription legislation, then in May the New Zealand Government followed suit and in July the catastrophic Somme offensive in Belgium got underway.

The Somme saw a dramatic increase in Australian troops killed or wounded. In the seven weeks after the attack began, the AIF lost close to 6,000 men and another 17,000 wounded. It seemed impossible that the AIF could replace its huge losses through voluntarism alone.

At the same time, enlistments in August were down to 6345 and according to the British War Council the AIF immediately needed a special draft of 20,000 men and a further 16,500 per month over the next three months to keep its numbers up to agreed levels.

Hughes returned from Europe believing that conscription was essential for Australia to fulfill its commitments. However, the Labor Party was split over the issue of compulsory overseas military service.

Because of a hostile Senate, Hughes could not amend the Defence Act 1903 to allow for overseas service. He decided to take the matter to the public by holding a popular vote. Although Hughes used a non-binding plebiscite to try and obtain a mandate, it was commonly referred to as a referendum.

Even though public support for conscription in the referendum would have no legal force, Hughes felt it would give him a mandate with which he could pressure the Opposition as well as opponents within his own Cabinet.

First referendum

The referendum was set for 28 October. The campaign incited, in the words of historian Joan Beaumont:

a public debate that has never been rivalled in Australian political history for its bitterness, divisiveness, and violence … What was at stake it soon emerged was not simply a disagreement about military need for conscription, but an irreconcilable conflict of views about core values: the nature of citizenship and national security; equality of sacrifice in times of national crisis; and the legitimate exercise of power within Australia’s democracy.

The debate split the country. The working class and unionists felt they were bearing the brunt of the war and voted predominantly against conscription.

Protestants with a connection to Britain voted in the majority to assist the Empire by introducing conscription, while Catholics, most of whom were of Irish background and opposed to the British handling of Irish independence, mostly voted against it.

Yet for all the animosity around the issue, most Australians still believed the war was a just cause.

The vote took place on 28 October after two months of feverish campaigning. The question put to voters was:

Are you in favour of the Government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the term of this War, outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service within the Commonwealth?

The result was ‘no’ by a margin of 3.2 per cent, but considering the entire apparatus of government and most of the media had been campaigning for ‘yes’ it was a significant victory for grassroots activism.

The political fallout from the referendum was profound. On 14 November the federal Labor caucus met and a vote of no-confidence in Billy Hughes’s leadership was successfully moved. Throughout the morning bitter debate ensued. In the afternoon Hughes called on those, ‘who think with me to follow me’.

Twenty-four Members of Parliament supported him and it was around this rump of the party that the incredibly resilient Hughes formed the new National Labor Party and, with support from the Liberals, formed a new government.

Second referendum

The Labor Party had split and would take years to regain its prewar power. Hughes remained Prime Minister for the rest of the First World War and continued to fight for conscription. The second referendum, held on 20 December 1917, was also voted down, this time by a larger majority.

On 11 November 1918 peace was finally declared. During the four years of the war, more than 420,000 Australians volunteered for the AIF, the Navy and the Nursing Corps, and 60,000 of that number died serving their country.

From our collection

Mikey Robins examines a mourning locket that belonged to the fiancee of boxer Les Darcy. He is joined by National Museum of Australia curator Jono Lineen. Darcy was a central figure in the 1916/17 conscription debate

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

Further reading

Billy Hughes, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Conscription fact sheet, National Archives of Australia

Conscription information, Australian War Memorial

Parliament and the war classroom resources, Parliamentary Education Office

John Barrett, Falling in: Australians and ‘Boy Conscription’, 1911–1915, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1979.

Joan Beaumont, Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2013.

JM Main, Conscription: The Australian Debate, 1901–1970, Cassell Australia, Melbourne, 1970.