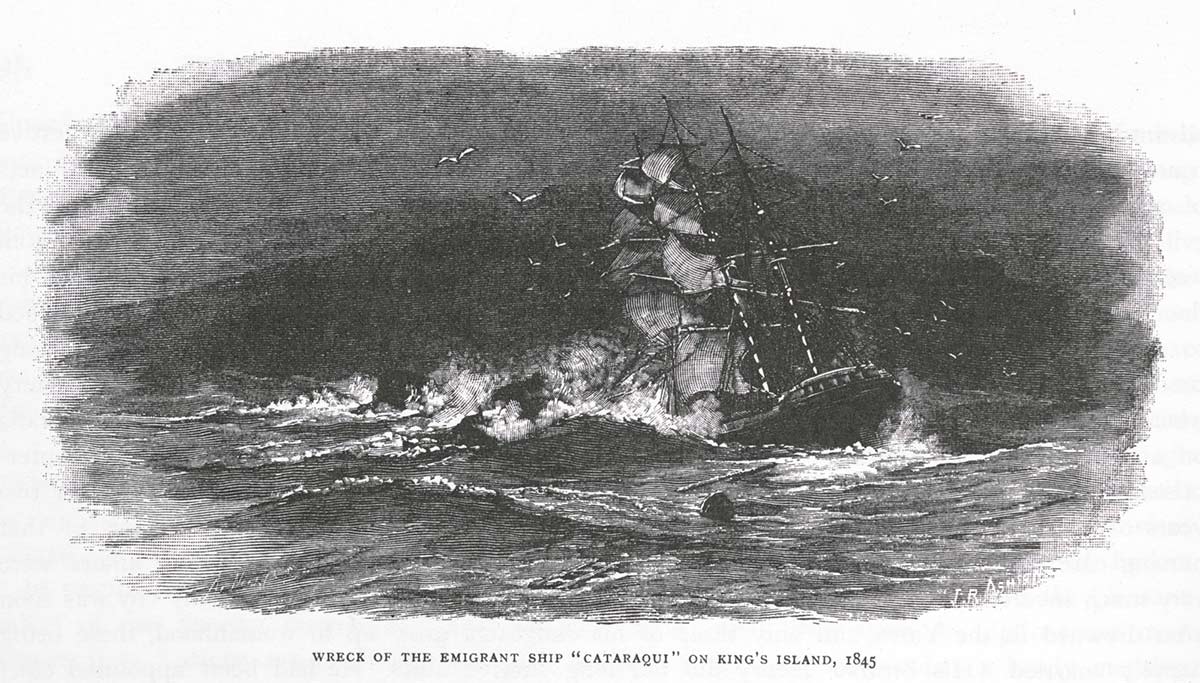

Australia’s largest civilian maritime disaster took place in 1845 when 400 people died as a result of the emigrant ship Cataraqui being wrecked off King Island in Bass Strait.

Report on the Cataraqui shipwreck to the editor, Port Phillip Patriot and Melbourne Advertiser, 14 September 1845:

Death stared them in the face in many forms – for it was not simply drowning, but violent dashing against the rocks which studded the waves between the vessel and the shore.

Assisted immigration schemes

As the economy of New South Wales grew in the early 19th century, the colony sought more workers from the United Kingdom to address its labour shortages.

From the 1820s governments and private entities established assisted immigration schemes, which provided incentives such as subsidised or free passage to skilled workers to encourage their relocation to the colony.

Following the passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, British church parishes could also sponsor poverty-stricken families in their counties to emigrate to Australia.

Lost at sea

Sea travel to Australia during the 19th century was risky. Ships and crews more familiar with seafaring in the Northern Hemisphere were often poorly equipped for the unfamiliar routes and heavy weather that they encountered on the voyage to the Antipodes.

Between 1850 and 1890, 155 vessels were wrecked in Bass Strait alone.

Cataraqui

The Cataraqui (or Cataraque) was an 815-tonne, 73-metre-long barque built in Quebec, Canada in 1840. William Smith and Sons of Liverpool, England, bought the ship with the intention of transporting emigrants to Australia.

It set sail for Melbourne from Liverpool on 20 April 1845 under the command of Captain Christopher Findlay. Many of the British and Irish passengers on board were assisted emigrants.

Sea voyage

The Cataraqui carried 411 people, comprising 367 emigrants, many of them women and children travelling in family groups, and 44 crew.

During the voyage, one crew member was lost overboard, six people died and five babies were born, leaving a total of 409 people onboard.

As the ship sailed through the Southern Ocean, it was besieged by a fortnight of heavy weather. Findlay prepared to enter Bass Strait, not realising that the storms had placed the ship 160 kilometres further east than he thought.

King Island

Bass Strait had become a popular shortcut for shipping between England and Sydney after its discovery in 1798–99. The route allowed sailors to save around a week of sailing time by avoiding a circumnavigation of Tasmania.

The time saved came at a cost: strong winds, uncertain currents, and incomplete and imperfect maps of the coastline made the passage treacherous. King Island, situated at the western entrance to Bass Strait, has a coastline that includes reefs and jagged rocks extending up to two kilometres offshore. In 1845 it was virtually uninhabited.

Shipwreck

At 4.30am on Monday 4 August 1845 in stormy weather, the Cataraqui struck a reef on the west coast of King Island less than 100 metres from shore. Around 300 passengers responded by climbing on to the deck, with large waves washing some out to sea.

Half an hour later, the ship listed to its port side, and passengers trapped below decks drowned as the ship filled with water.

The following morning, some 200 surviving passengers and crew still clung onto the deck, but at 4pm the ship broke in two, launching up to 100 survivors into the turbulent waters.

The crew tried to provide a lifeline to the shore when they launched a buoy attached to a rope, but it became caught in kelp 20 metres from the beach. At 5pm the wreck further disintegrated, leaving around 70 survivors clutching the bow.

The crew launched a small boat, but it capsized in the wild conditions, drowning all six onboard.

However, the buoy rope was retrieved and used to secure survivors to the deck overnight as the stormy weather continued. But casualties continued to mount, with only 30 people alive the following morning. Those remaining tried to float to shore on debris, shortly before the ship sank.

There were only nine survivors – one passenger, Solomon Brown, and eight crew. Four hundred passengers and crew had perished in the disaster.

Aftermath of the Cataraqui wreck

The survivors had little food and no water, and sheltered overnight under a wet blanket washed ashore from the wreck.

The following day David Howie, a former convict who was on the island to barter animal skins from Aboriginal inhabitants, discovered the survivors after noticing wreckage in the water.

Howie provided shelter and provisions to the survivors, but because his own boat was wrecked he had no means of helping them to leave the island.

Five weeks later, on 7 September 1845, a passing vessel, the Midge, rescued the group and took them to Melbourne.

Within weeks, the wreckage had been auctioned off and the Superintendent of Port Phillip District, Charles La Trobe, arranged for Howie to bury the shipwreck victims on King Island.

The Admiralty banned the use of Bass Strait from 1846, until the completion of a lighthouse at Cape Otway on the mainland in 1848. Lighthouses on King Island were completed at Cape Wickham in 1851 and Currie in 1879. Even so, ships continued to wreck along the coasts of the island throughout the 19th century.

The British Admiralty banned the use of Bass Strait from 1846, until the completion of a lighthouse at Cape Otway on the mainland in 1848. Lighthouses on King Island were completed at Cape Wickham in 1851 and Currie in 1879. Even so, ships continued to wreck along the coasts of the island throughout the 19th century.

You may also like

References

Cataraqui, Australian National Shipwreck Database

Graeme Henderson, Swallowed by the Sea: The Story of Australia’s Shipwrecks, NLA Publishing, Canberra, 2016.

Andrew Lemon and Marjorie Jean Morgan, Poor Souls, They Perished: The Cataraqui, Australia’s Worst Shipwreck, Hargreen, North Melbourne, 1986.