The Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804 was Australia’s first uprising.

The rebellion was an attempt by a group of Irish convicts to overthrow British rule in New South Wales and return to Ireland where they could continue to fight for an Irish republic.

Ending in disaster, the ill-fated rebellion resulted in the death of at least 39 convicts in both ‘Australia’s Battle of Vinegar Hill’ and the ensuing martial law punishments.

The 1804 Castle Hill Rebellion (or the Battle of Vinegar Hill) in live-sketch animation, as told by historian David Hunt.

Political prisoners sent to Australia

Transportation to the Australian colonies was initially reserved for convicted criminals, such as thieves and counterfeiters. However, in the wake of the 1789 French revolution, and fearing the influence of radical dissenters, Britain also began transporting political prisoners.

In 1798 there was a bloody rebellion against British rule in Ireland. Major battles were fought, one of the most infamous being the Battle of Vinegar Hill in County Wexford, where rebels were crushed by British forces. Many Irish men and women were sentenced to transportation for their role in the uprising.

In Australia they remained desperate to fight against British injustice, return home and continue to support the Irish cause. Because of this, unrest in penal settlements was rife. Between 1800 and 1804 many small rallies and uprisings were planned in the Sydney region, but were thwarted before they began.

Death or liberty

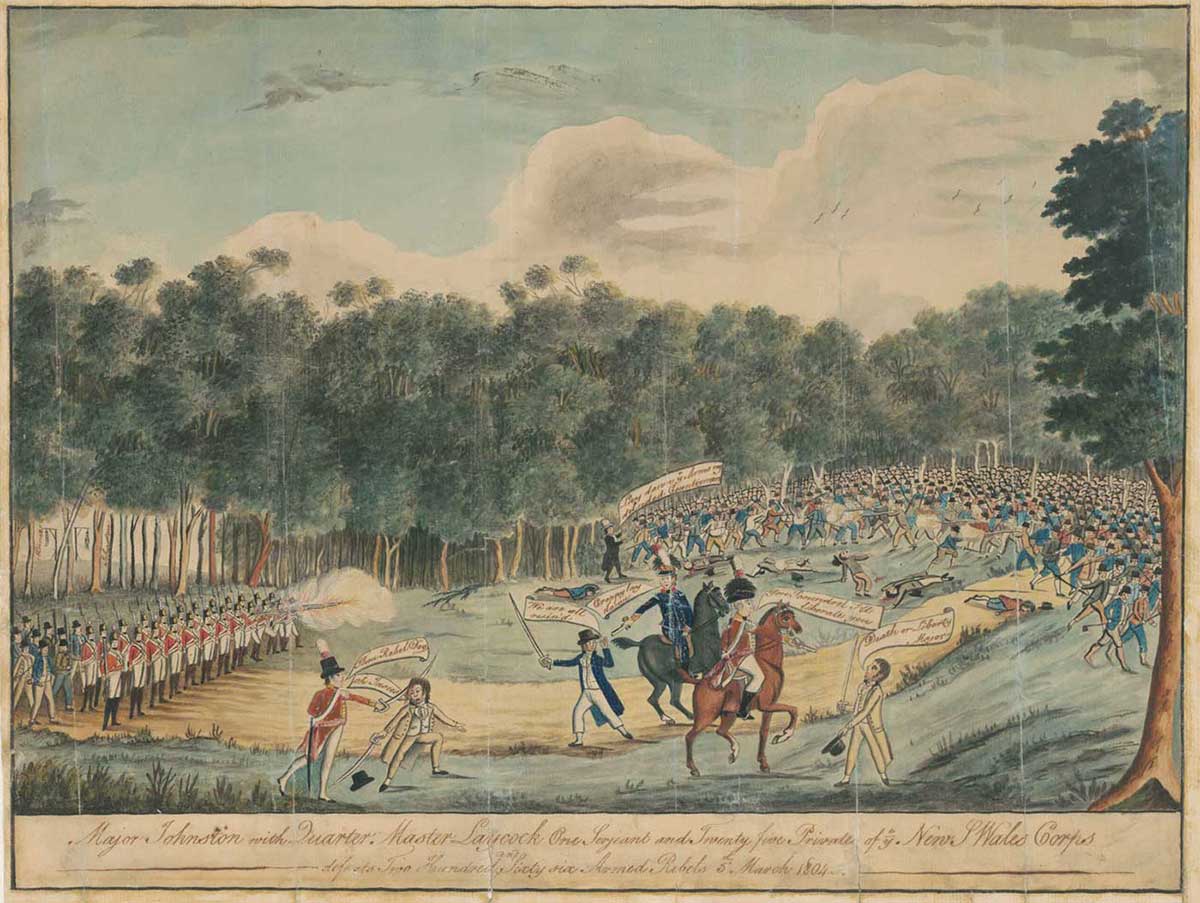

The Castle Hill Rebellion or ‘Australia’s Vinegar Hill’ began on 4 March 1804. Rebel leaders – Irishmen Philip Cunningham (a veteran of the 1798 rebellion) and William Johnston – aimed to overtake Parramatta and Port Jackson (Sydney), establish Irish rule and return willing convicts to Ireland.

The plan involved joining with around 1,000 other convicts planning to escape from the Hawkesbury region before moving on the settlements. ‘Death or Liberty’ was adopted by the rebels as their rallying call.

As darkness fell, a hut at Castle Hill Government Farm was set alight as a signal to begin. Around 300 convicts overpowered their guards and took supplies and munitions. The group was split into smaller parties and sent to raid nearby farmhouses. However, many became lost during the night and did not return to the rendezvous point just outside of Parramatta, reducing the convict force.

A messenger tasked with delivering rebel orders to convicts in the Hawkesbury region surrendered to authorities and informed them of the plan. Cunningham, unaware that his reinforcements would never arrive, moved the remaining convicts towards the Hawkesbury.

Alerted to the rebellion late in the evening, New South Wales Governor Philip Gidley King declared martial law and Major George Johnston of the New South Wales Corps organised troops and civilian volunteers from the Sydney settlement to pursue the convicts. Government forces undertook a forced march through the night until they came within a few kilometres of the rebels.

Riding ahead while the main group continued on foot, Major Johnston, trooper Thomas Anlezark and Father Dixon (a Catholic priest) attempted to convince the rebels to surrender. They met with the response: ‘death or liberty, and a ship to take us home’.

When Johnston approached the convict leaders a second time, he and Trooper Anlezark took advantage of surprise caused by the sudden appearance of government troops and captured Cunningham and another rebel leader.

While retreating with Cunningham, Major Johnston ordered government forces to fire on the convicts: 15 were killed, the others scattering into the bush. At least 15 more convicts were killed in ongoing pursuits, and the majority surrendered or were recaptured.

Aftermath of the Castle Hill Rebellion

After the rebellion King had Cunningham and eight others hanged without trial. It is estimated that 39 convicts died in, or as a result of, the uprising, although accurate numbers may never be known.

Seven convicts were sentenced to between 200 and 500 lashes and, with another 23 rebels, were then banished to the Coal River (Newcastle) chain gang.

While the Castle Hill rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful, it did serve as inspiration for another famous uprising. Identifying with the ideals of liberty, justice and freedom espoused by the Irish rebels both in Australia and in Ireland, the participants in the Eureka Stockade in 1854 used the secret password ‘Vinegar Hill’.

In our collection

You may also like

References

Anne-Maree Whitaker, The Castle Hill convict rebellion 1804, Dictionary of Sydney, 2009

Tony Moore, Death or Liberty: Rebels and Radicals Transported to Australia 1788–1868, Pier 9, Sydney, 2010.

Lynette Ramsay Silver, The Battle of Vinegar Hill: Australia’s Irish Rebellion, The Watermark Press, Sydney, 2002.