From October 1942 to October 1943 the Japanese army forced about 60,000 Allied prisoners of war (POWs) – including 13,000 Australians and roughly 200,000 civilians, mostly Burmese and Malayans – to build a railway linking Thailand and Burma.

The railway has entered the Australian consciousness as a byword for courage and resilience in the face of extreme hardship and cruelty. About 2800 Australians died building the railway.

On 24 May 1943 Australian soldier Brigadier Arthur Varley wrote in his diary:

The Japanese will carry out [their] schedule and do not mind if the line is dotted with crosses. [1]

Japanese conquests

At the start of the Second World War, Australia deployed most of its armed forces to help Britain fight the Germans and Italians in Europe and North Africa.

In February 1941 with the threat of an impending war with Japan, Australia dispatched part of the newly formed 8th Division to Singapore and Malaya to reinforce British troops.

On 7 December 1941 the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the US Navy base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, followed swiftly by attacks on other US and British strategic points around the Asia–Pacific region.

The same day, the Imperial Japanese Army invaded the Malay Peninsula (though it was 8 December there, owing to the International Date Line). By 15 February the Japanese had taken Singapore, capturing 130,000 Allied personnel, including 15,000 Australian soldiers.

Meanwhile, the Japanese defeated Australian units on Java, New Britain, Timor and Ambon, bringing the total number of Australians captured to 22,000.

Building the Burma–Thailand Railway

The Battle of Midway, which took place in early June 1942, was a turning point in the Pacific War. It was a decisive victory for the US Navy and greatly reduced the Japanese Navy’s ability to defend the main supply routes which were needed to provision and reinforce Japanese forces in Burma, in preparation for a planned invasion of India.

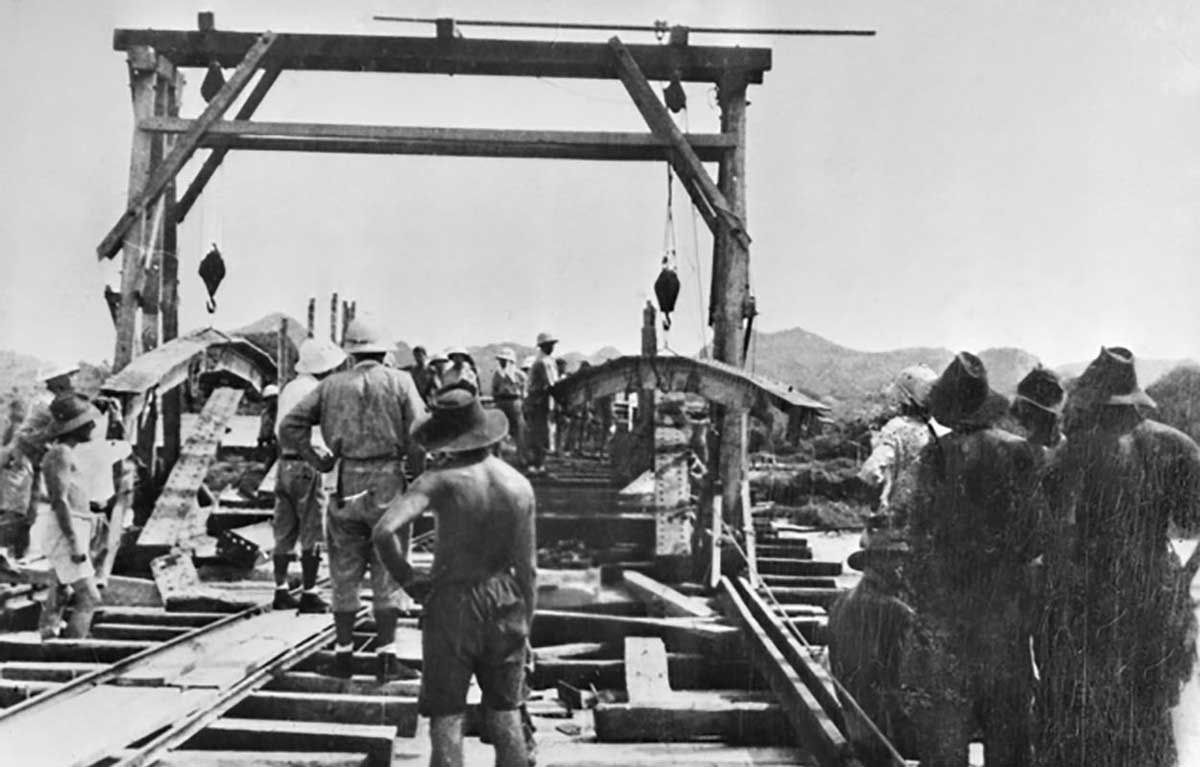

As an alternative, the Japanese decided to build a 415-kilometre railway from Thailand to southern Burma. All but 50 kilometres of the route was across rugged terrain covered in dense, malarial jungle. It would require building more than 600 bridges as well as hundreds of viaducts, embankments and cuttings.

The Japanese drew on two sources of labour. The largest group was made up of roughly 200,000 local men, women and children who were either forced or offered money to work on the railway. These people were mostly Burmese and Tamils from Malaya, but also Thais and Javanese, among others.

The second group comprised Allied POWs, most of whom were British, Australian and Dutch soldiers. About 60,000 were sent to work on the railway; 13,000 of them were Australian.

Life and death on the railway

The railway took 12 months to build, with final completion on 16 October 1943.

Rather than start at both ends and meet in the middle, the Japanese made full use of their enormous workforce by setting up more than 100 camps along the route and building sections of the line simultaneously.

Conditions in the camps were horrendous, particularly at the more remote sites where resupply of food, equipment and medical supplies was difficult.

The mortality rate was very high, particularly among the Asian labourers. More than a quarter of Allied POWs would die by the end of war and nearly half of the Asian labourers. The main causes of death were maltreatment, starvation, overwork and disease.

The work itself was gruelling and dangerous. Apart from building bridges, it involved clearing jungle, then constructing embankments or cuttings on steep hills to ensure the gradient of the track was gentle enough for the trains.

The Japanese and conscripted Korean guards forced the prisoners to toil to exhaustion day after day. They savagely beat anyone who they decided was not working hard enough, and demanded that even the seriously ill work.

The diet primarily consisted of a thin gruel made from rice and a very small amount of vegetables. By the end of the war all the survivors looked like living skeletons. Poor diet contributed to the prevalence of serious diseases, such as beri-beri (caused by vitamin B deficiency), cholera, malaria, dysentery and flesh-eating tropical ulcers.

The 44 Australian medical officers who worked on the railway were sorely overworked and had to make do with primitive hospitals and an almost total lack of medicines. The most famous of these doctors was Lieutenant Colonel Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop, whose courage and compassion came to symbolise the incredible spirit of those who worked and died on the railway.

The reasons for the Japanese cruelty were complex, and while many guards treated the prisoners abominably, not all did. In the immediate postwar years, Australia tried 924 Japanese servicemen for war crimes across the Asia–Pacific. A total of 644 were convicted and 137 executed. Of these, 111 were convicted and 32 executed specifically for crimes committed on the Burma–Thailand Railway.

Allied prisoners of war in the Asia–Pacific

More than 20 per cent of Australian prisoners working on the railway died. Unfortunately it was not the most lethal place to be a prisoner of the Japanese during the war. Of the 532 Australians captured on Ambon Island, nearly 80 per cent died. Of the 2500 Australian and British POWs sent to the camp at Sandakan in Borneo in 1942, only six survived, all Australians.

The Japanese moved Allied prisoners, including Australians, around the region on what became known as ‘hell ships’. As the name suggests, the conditions on these dilapidated vessels were appalling – they were overcrowded, hot and unventilated, with little food, water or regard for sanitation.

Some vessels were even sunk by Allied submarines, which had no way of knowing that the ships were carrying prisoners. Thousands of POWs drowned this way.

Legacy

The railway was completed in October 1943. The Japanese were able to use it to supply their troops in Burma despite the repeated destruction of bridges by Allied bombing.

More than 90,000 Asian civilians died on the railway, as well as 16,000 POWs, of whom about 2800 were Australian.

In the decades since the war, Australian POWs have entered the national consciousness as Anzacs who triumphed over adversity, displaying humour, resourcefulness and mateship in the worst circumstances.

The railway itself has not been used in its entirety since the war. Much of it has been torn up or become overgrown. Some sites – such as Hellfire Pass and the Wampo Viaduct – have since become tourist destinations.

Notes

[1] Brigadier Varley, an Australian serviceman, commanded around 9,000 POWs at the Burmese end of the Burma–Thailand Railway. This quote is from a secret diary he buried before boarding a ‘hell ship’ that was sunk en route to Taiwan in September 1944. Varley did not survive. The diary was retrieved after the war and used as evidence in war crimes trials.

Explore defining moments

References

Fall of Singapore symposium audio, National Museum of Australia

The Thai–Burma Railway and Hellfire Pass, Anzac portal

Joan Beaumont, Lachlan Grant and Aaron Pegram (eds), Beyond Surrender: Australian Prisoners of War in the Twentieth Century, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2015.

Gavan McCormack and Hank Nelson (eds), The Burma–Thailand Railway, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1993.

Pattie Wright, The Men of the Line: Stories of the Thai–Burma Railway Survivors, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2008.