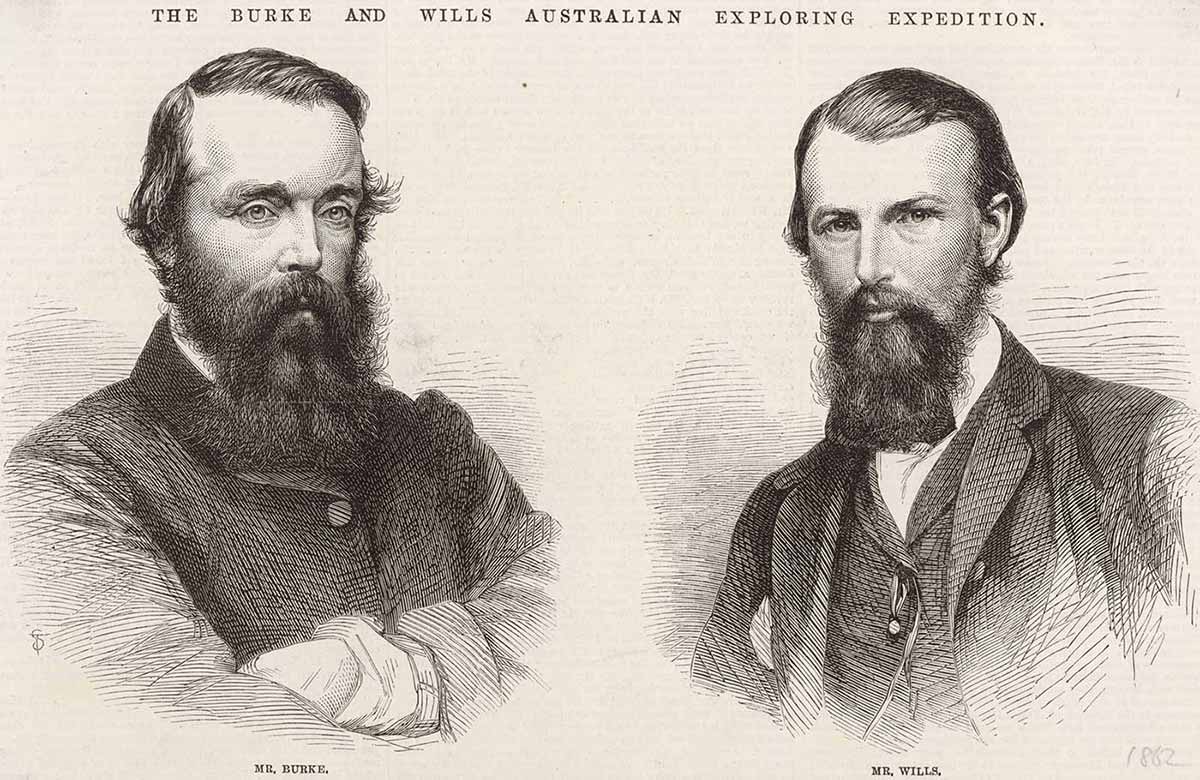

Robert O’Hara Burke, William John Wills, John King and Charles Gray became the first Europeans to cross Australia south to north when they reached the Gulf of Carpentaria in February 1861.

The death of Burke, Wills and Charles Gray during their return led the expedition to be mythologised in Australian culture as a heroic failure. It ultimately prompted the discovery of vast grazing lands, enabling further European settlement of the interior.

Robert O’Hara Burke, Cooper Creek, 26 June 1861:

I hope we shall be done justice by. We fulfilled our task but we were … not followed up as I expected and the Depot party abandoned their post … King has behaved nobly and I hope he will be properly cared for.

Victorian Exploring Expedition

In 1860 much of the interior of Australia remained uncharted. Some Victorians, made wealthy from the gold rushes, were prepared to fund exploratory expeditions.

They had three goals: scientific discovery, seeking new grazing land and finding a route for an overland telegraph line.

South Australian explorer John McDouall Stuart had already discovered productive grazing country during several expeditions from Adelaide to north of Lake Eyre by the late 1850s.

The Victorian Government and the Royal Society of Victoria, spurred by a desire to maintain Victoria’s position as the ‘most advanced’ colony, funded the Victorian Exploring Expedition and set it the task of being the first to traverse Australia from south to north.

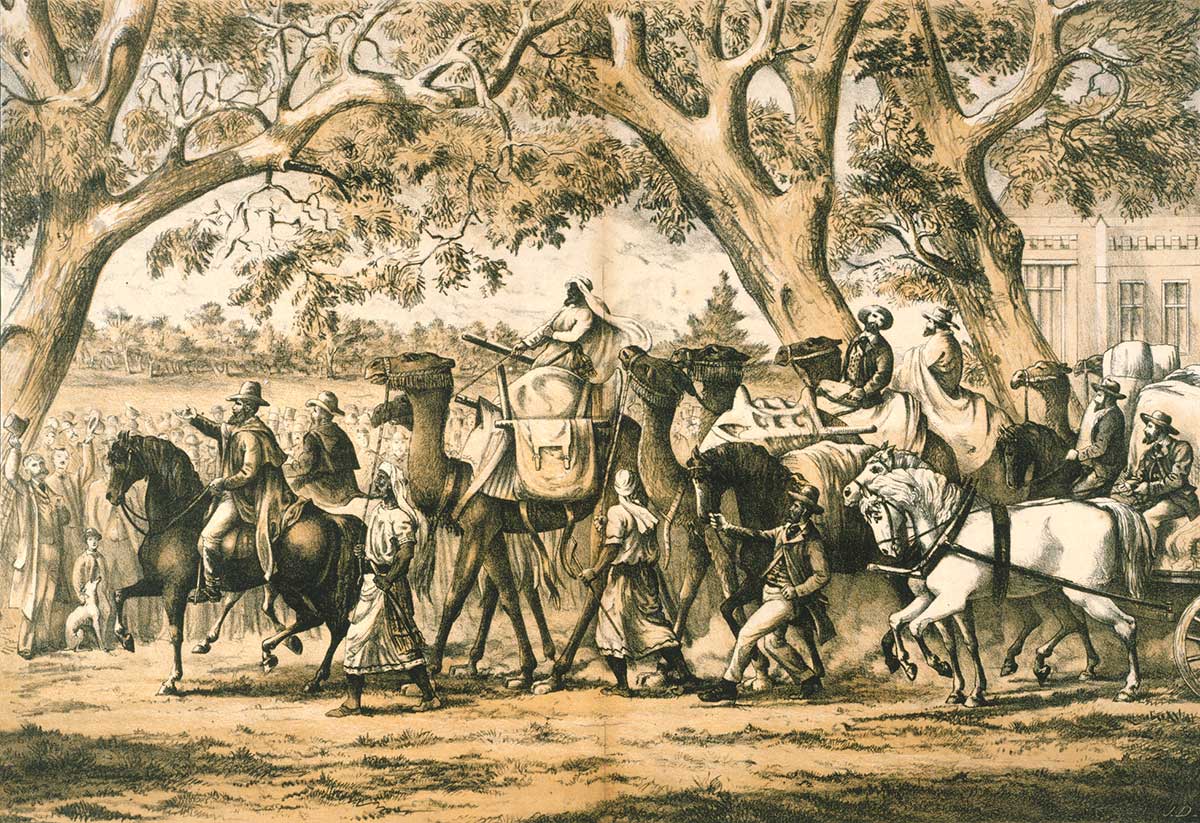

The expedition, one of the most expensive in Australian history, was led by Robert O’Hara Burke, an Irishman with no exploration experience or skills in surveying or navigation. It was lavishly equipped with items including 50 gallons of rum to revive tired camels (there were 27 of them), and an oak table.

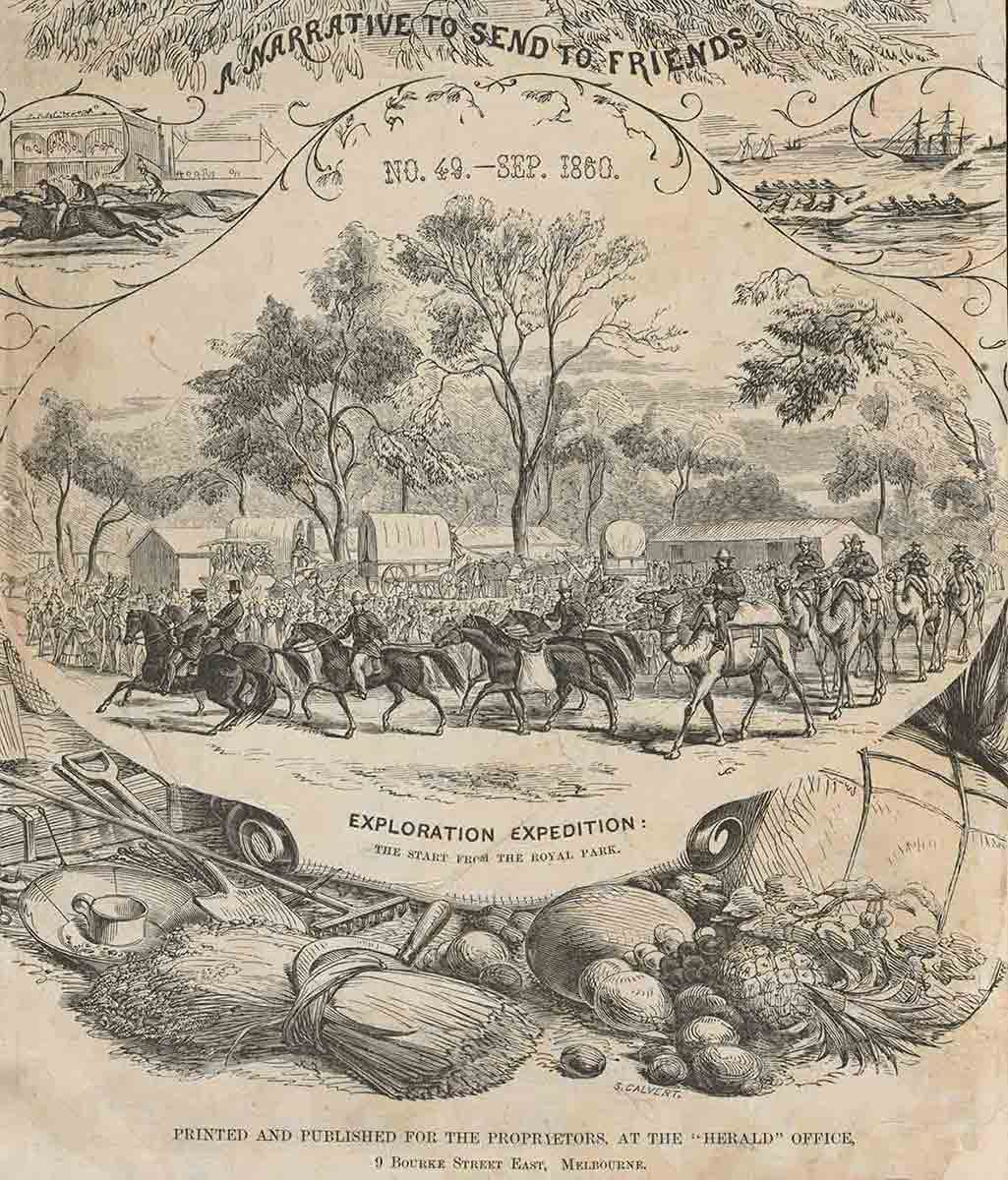

The expedition’s departure from Royal Park, Melbourne on 20 August 1860 was a public spectacle watched by about 15,000 people.

Burke divides the party

The expedition reached Menindee near Broken Hill in New South Wales on 23 September 1860. Burke decided to leave most of the equipment there while he led a small advance party to Cooper Creek in western Queensland to establish a ‘depot’.

Burke left Menindee local William Wright in charge of supplies with instructions to bring these to Cooper Creek ‘soon’. However, three months passed before Wright left Menindee.

Burke’s party arrived at Cooper Creek on 11 November 1860. Just over a month later he divided the exploring party again, setting off with Wills, King and Gray for the Gulf of Carpentaria. William Brahe was left in charge of the depot with instructions to wait three months for their return.

Reaching the Gulf of Carpentaria

On about 9 February 1861 the four expeditioners reached the Bynoe River, near the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Burke and Wills left the other two and tried to walk to the ocean but were unable to find a way through the mangrove swamps. The party started their return journey to Cooper Creek on 12 February 1861.

On 17 April 1861, four days before reaching their destination, Gray died from malnutrition.

Mischance and the Dig Tree

Wright’s supply party finally left Menindee for Cooper Creek on 26 January 1861.

Extreme heat and illness forced the party to rest at the Bulloo River where Charles Stone, William Purcell and Ludwig Becker died of malnutrition and dysentery between 22 and 29 April. On 5 June 1861 William Patton also died.

Meanwhile, at the Cooper Creek depot, Brahe who had waited four months for Burke’s return, decided to return to Menindee on 21 April 1861.

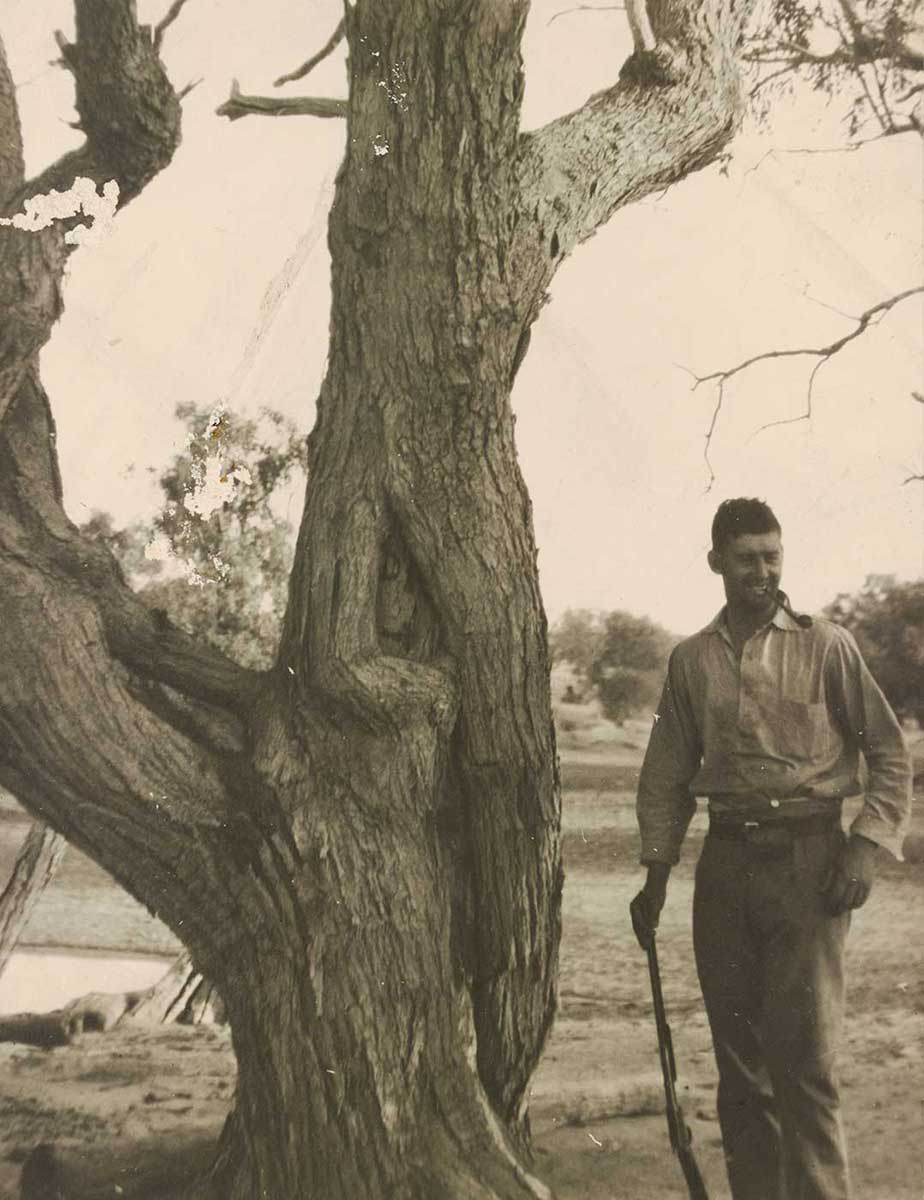

He buried a cache of food and a note stating his intention at the foot of a coolabah tree. Into the tree he engraved the directions, ‘DIG 3FT NW APR 21 1861’. The tree has entered Australian folklore as the ‘Dig Tree’.

About nine hours after Brahe departed, Burke, Wills and King arrived. They found the cache, which had enough supplies for a month, but instead of following Brahe back to Menindee or staying at the depot, on 22 April 1861 they decided to head south west to try to reach a station at Mount Hopeless.

Communication failure

Burke, Wills and King buried a message of their own under the Dig Tree explaining their plans. They were careful to leave no trace that they had been there, so that Aboriginal people would not dig up the letter.

Their efforts were so successful that Brahe, who had encountered Wright’s supply party on 29 April, and had returned with Wright to the Cooper Creek depot on 8 May, believed that the Dig Tree cache remained undisturbed and that Burke’s party had not returned from the Gulf.

Brahe too left no indication of his visit, so that when Wills doubled back for one last look at the depot on 27 May 1861, he found nothing to suggest that anyone had returned to search for them.

Burke and Wills die

Burke and Wills died within a few days of each other at the end of June 1861.

Wills died alone, having urged the other two to leave him and keep searching for Yandruwandha people who had been generous with their food and hospitable since the expeditioners had arrived at Cooper Creek.

Up to this point, these overtures of cooperation had been met with suspicion and sometimes hostility by the explorers.

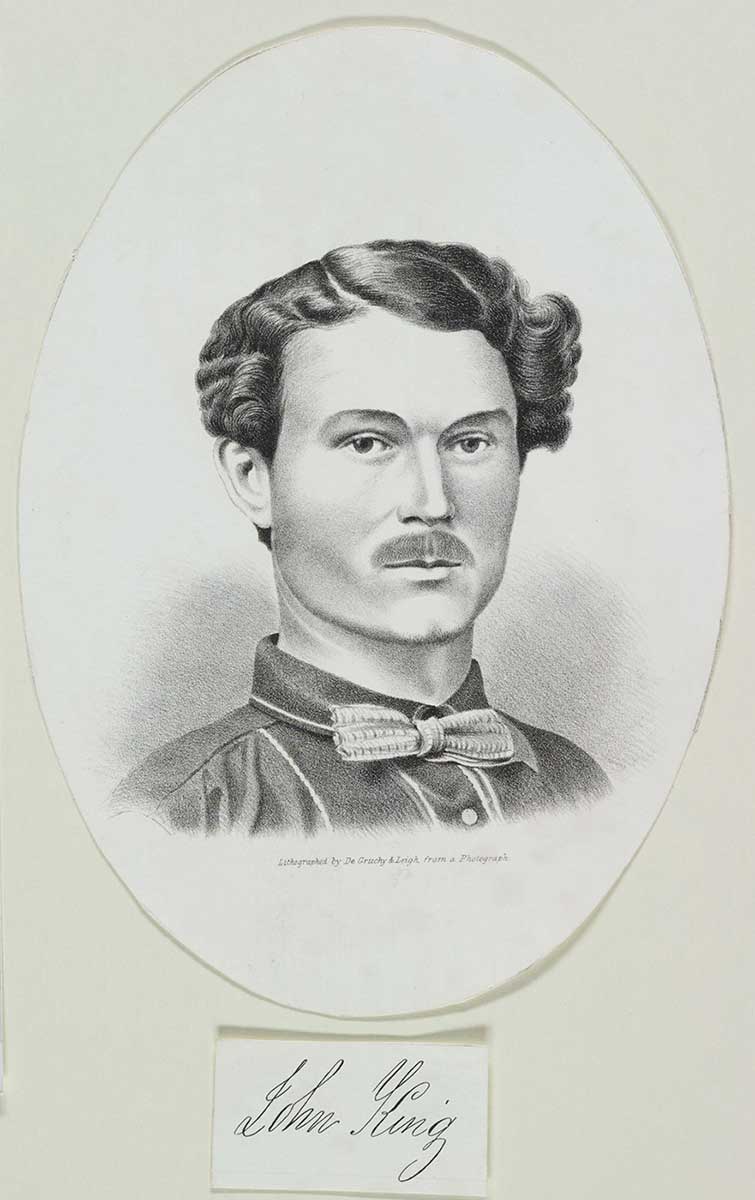

King eventually found the Yandruwandha people, who accepted him into their community and saved his life.

In his 1861–62 testimony on the Yandruwandha, King said, ‘They appeared to feel great compassion for me when they understood that I was alone on the creek, and gave me plenty to eat.'

Indigenous knowledge

Burke and Wills died of malnutrition, which was accelerated by the onset of beri-beri – a deficiency of thiamine, vitamin B1. The explorers contracted beri-beri by eating nardoo, a clover-like plant which contains an enzyme that breaks down thiamine

Nardoo was regularly eaten by the Yandruwandha people. They carefully prepared the plant to eliminate the enzyme and gave it to the explorers. Burke and Wills, however, ate the plants raw.

Victoria mourns

On 15 September 1861 a Victorian relief party led by Alfred Howitt and Edwin Welch found King living with the Yandruwandha.

The bodies of Wills and Burke were also found and buried. Their remains were later recovered and re-buried in Melbourne. They were given Australia’s first state funeral on 21 January 1863.

Pastoral expansion

Relief parties from Victoria, Queensland and South Australia sent to search for Burke and Wills, discovered valuable new grazing lands which resulted in increased European settlement of the interior.

While Burke, Wills, King and Gray were the first Europeans to cross Australia from south to north, it was Stuart who found an all-weather route from Adelaide to the Arafura Sea in 1862.

In our collection

Explore defining moments

References

Burke and Wills Dig Tree, Queensland Heritage Register

Burke, Wills, King and Yandruwandha, Dept of the Environment and Heritage

Dig: The Burke and Wills research gateway, State Library of Victoria

Tim Bonyhady, Burke & Wills: From Melbourne to Myth, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1991.

Ian Clarke and Fred Cahir (eds), The Aboriginal Story of Burke and Wills: Forgotten Narratives, CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, 2013.