On 6 July 2019 Budj Bim Cultural Landscape became the first site in Australia to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List purely for its Aboriginal cultural significance.

It is one of the world’s oldest and most extensive aquaculture sites, dating back at least 6,600 years. Gunditjmara traditional owners first proposed the site for world heritage listing in 1989.

Denis Rose, Gunditjmara traditional owner, 2019:

For us to get to this stage has been a long journey. I’d like to acknowledge our Gunditjmara ancestors who have led the way for us. We know they are still here with us and their ingenuity still shows in the aqua culture systems that are still operational to this day.

UNESCO World Heritage Listing

The world heritage nomination for the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape was presented to the 43rd session of the World Heritage Committee in Baku, Azerbaijan, in June–July 2019. It was prepared by the Gunditjmara traditional owners, with the support of both the federal and state governments.

The addition of the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape to the list marks the first site in Australia to be recognised purely for its Aboriginal cultural significance.

The UNESCO World Heritage List contains over 1,000 sites from around the world that are of natural and/or cultural significance. Once a site is added to the list, it is protected by international treaties. There are currently 20 Australian sites on the list.

Ancient aquaculture site

The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape is located in the traditional country of the Gunditjmara Aboriginal people in south-western Victoria. It is one of the oldest and most extensive aquaculture sites in the world.

Basalt stone deposits from lava flows have been used to construct a complex system of stone channels, weirs and traps within the natural features of the landscape. These man-made structures have provided a plentiful supply of food, including eels, fish and turtles, for the Gunditjmara people for millennia.

There are also remains of many circular stone-walled houses spread throughout the Budj Bim landscape.

Volcanic landscape

Volcanic eruptions initially formed Budj Bim (formerly Mount Eccles) around 27,000 years ago. The volcano erupted at least 10 times, with the most recent eruption dating to about 7,000 years ago.

The Tyrendarra lava flow extends 50 kilometres to the south, beyond the current coastline. The sharp jagged rock formations diverted the natural water flow and formed Tae Rak (Lake Condah) and Condah Swamp.

There are three components to the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape: Budj Bim (northern component), Kurtonitj (central component) and Tyrendarra (southern component).

Gunditjmara engineering

The Budj Bim lava flows created a landscape of lakes, ponds and swamps rich in aquatic life.

The Gunditjmara people engineered a complex system of fish traps which combined their knowledge of the seasonal rise and fall of water levels with these natural formations.

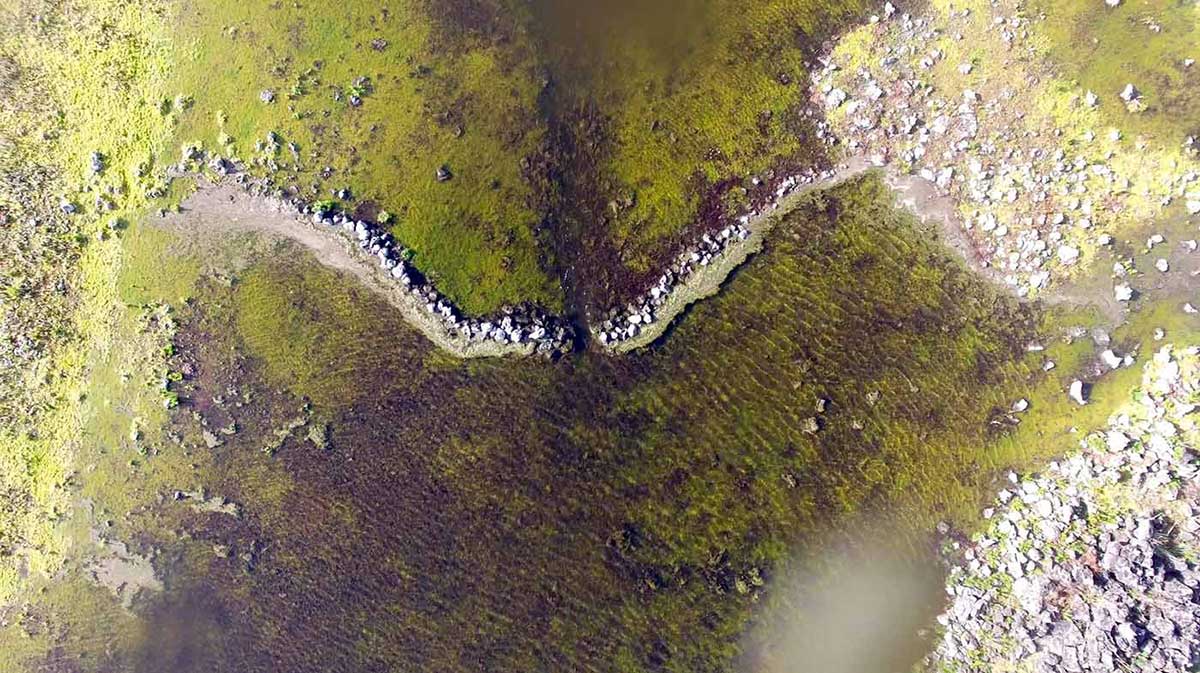

Shallow channels, some up to 200 metres long, were dug out of the rock to divert water. Stones were used to build features such as V-shaped traps and weirs.

Short-finned eels (Anguilla australis) were trapped by placing long, funnel-shaped woven baskets in the weirs. Turtles and fish were also harvested from the aquaculture system.

Kooyang (short-finned eel)

The trapping, harvesting and farming of eels provided a plentiful supply of food for the Gunditjmara people. The eels were a valuable commodity and were traded at meetings with other Aboriginal language groups.

Some eels were kept alive in holding and growing ponds, and then eaten later. Eels were also preserved by smoking in the hollows of large trees.

The freshwater ponds and wetlands of the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape provide ideal conditions for eels. When the eels reach maturity they migrate to the mouth of the river before making the journey out to sea. The eels spawn near Vanuatu and the larvae eels drift back to the eastern Australian coastline with the ocean currents.

Denis Rose, Gunditjmara traditional owner, 2019:

Gunditjmara wealth came from the rich ecosystems, coasts, wetlands, the plant and animals, and the interweaving of our culture in their management and use.

Time of unrest

The seasonal presence of whalers and sealers began to have an impact on the Gunditjmara people from around 1810. In 1834 Edward Henty, the first European settler in the Portland area, arrived.

In the 1840s conflict arose between the settlers and the Gunditjmara people in what came to be known as the Eumeralla Wars. By 1846 the resistance of the Gunditjmara had been suppressed.

During the 1850s Aboriginal people across Australia were largely moved into centralised church-run missions. Framlingham Mission opened in the Western District of Victoria, but the Gunditjmara from along the Budj Bim landscape refused to settle there. They identified Tae Rak (Lake Condah) as the place where they should be.

In response to this resistance, Lake Condah Mission was opened in 1867. It was located close to the traditional lands of the Gunditjmara. By the 1880s more than 70 people were living there. Similar missions, set up under the guise of protection, sought to concentrate Aboriginal people and enforce European culture on them.

In 1886 the population of the Lake Condah Mission dropped significantly after the Aborigines Protection Act 1886 (Vic) declared that Aboriginal people of mixed descent were no longer allowed to live at the mission.

The mission officially closed in 1918. However, Gunditjmara people continued to live on the site until 1939. The mission lands were returned to the Gunditjmara in 1987.

In our collection

In our collection

You may also like

References

Ian D Clark and Victorian Tourism Commission, Koorie Tourism Unit, People of the Lake: The Story of Lake Condah Mission, Victorian Tourism Commission, Melbourne, 1990

The Gunditjmara people with Gib Wettenhall, The People of Budj Bim: Engineers of Aquaculture, Builders of Stone House Settlements and Warriors Defending Country, em PRESS, Heywood, Vic., 2010

National heritage places – Budj Bim national heritage landscape