The first case of bubonic plague in Australia was reported in January 1900. Bubonic plague is one of the deadliest diseases humanity has ever faced. The ‘Black Death’ of the 14th century killed a quarter of Europe’s population.

In 20th century Australia, however, there were relatively few deaths due to a coordinated response from health authorities and government.

Sydney Morning Herald, 7 March 1900:

Our sewerage system is excellent, we have a properly organised municipal health department … if the bubonic plague should have the effect of galvanising the Municipal Council of Sydney into renewed interest in this question of municipal hygiene it would at least serve one good purpose.

What is bubonic plague?

The bubonic plague, or ‘Black Death’ as it became known during the pandemic of the 17th century, is one of the most deadly diseases to which humans have ever been exposed.

The disease is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis (Y pestis). The bacterium firstly infects the rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis), which then infect its host, usually the black rat (rattus rattus). Black rats commonly live close to humans and feed on stored produce such as grain. The fleas move from the rats to humans who, once bitten, become infected.

The disease Y pestis moves quickly from the site of infection into the lymphatic system. The bacterium causes acute inflammation of the lymph nodes. When the nodes break down, the toxins spread through the body causing massive haemorrhaging in the internal organs, discolouring the skin – hence the name 'Black Death'.

History of the bubonic plague

The three major bubonic plague pandemics are among the greatest natural disasters of all time.

In 541CE the plague arrived in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire and the largest city in the world.

Evidence points to Y pestis having been carried north from Sudan on the Nile River aboard grain ships, and then across the Mediterranean Sea.

Over the following year, the plague killed 40 per cent of Constantinople’s population and eventually a quarter of the population of the eastern Mediterranean.

The plague spread across Europe, reaching England by 664. Frequent smaller outbreaks occurred across Europe until 750 when the disease disappeared.

In 1348 the plague erupted again in Europe, when Genoese soldiers returning from the siege of Kaffa in the Crimea unknowingly transported Y pestis back to Italy.

Plague spread rapidly across the continent and was most virulent between 1348 and 1356. The pandemic became the deadliest event in human history, killing a quarter of the people in Europe.

Such devastation had far-reaching effects. It contributed to the end of the feudal system in Europe as there were no longer enough peasants to work the large estates. Civic administration separated from the church. And scientific inquiry was stimulated in an attempt to understand the disease.

The 14th century outbreak lingered across Europe, with smaller epidemics occurring until 1720.

Australia and the third pandemic

The third great bubonic plague pandemic started in northern China in 1855. By 1894, it had reached Hong Kong, with 100,000 deaths reported that year. In 1896 the plague spread to India and in 1899 Noumea was declared a plague-infected port.

Australian colonial authorities were acutely aware that it was only a matter of time before the disease reached the continent.

The first case reported in Australia was that of Arthur Paine on 19 January 1900. He was a delivery man who worked at Central Wharf where the ship carrying infected rats would have docked. By the end of February, 30 cases had been reported and the government was concerned the colony was on the brink of an epidemic.

Disease control

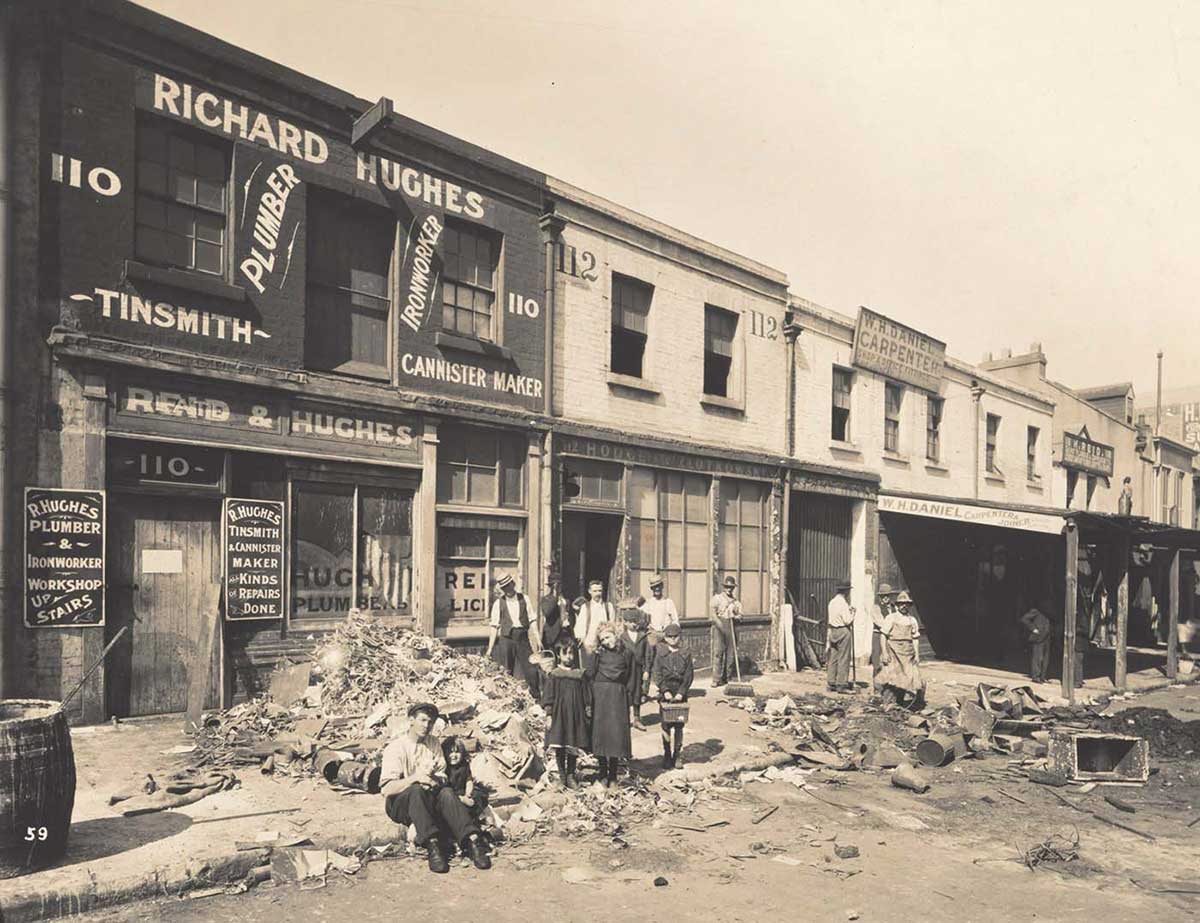

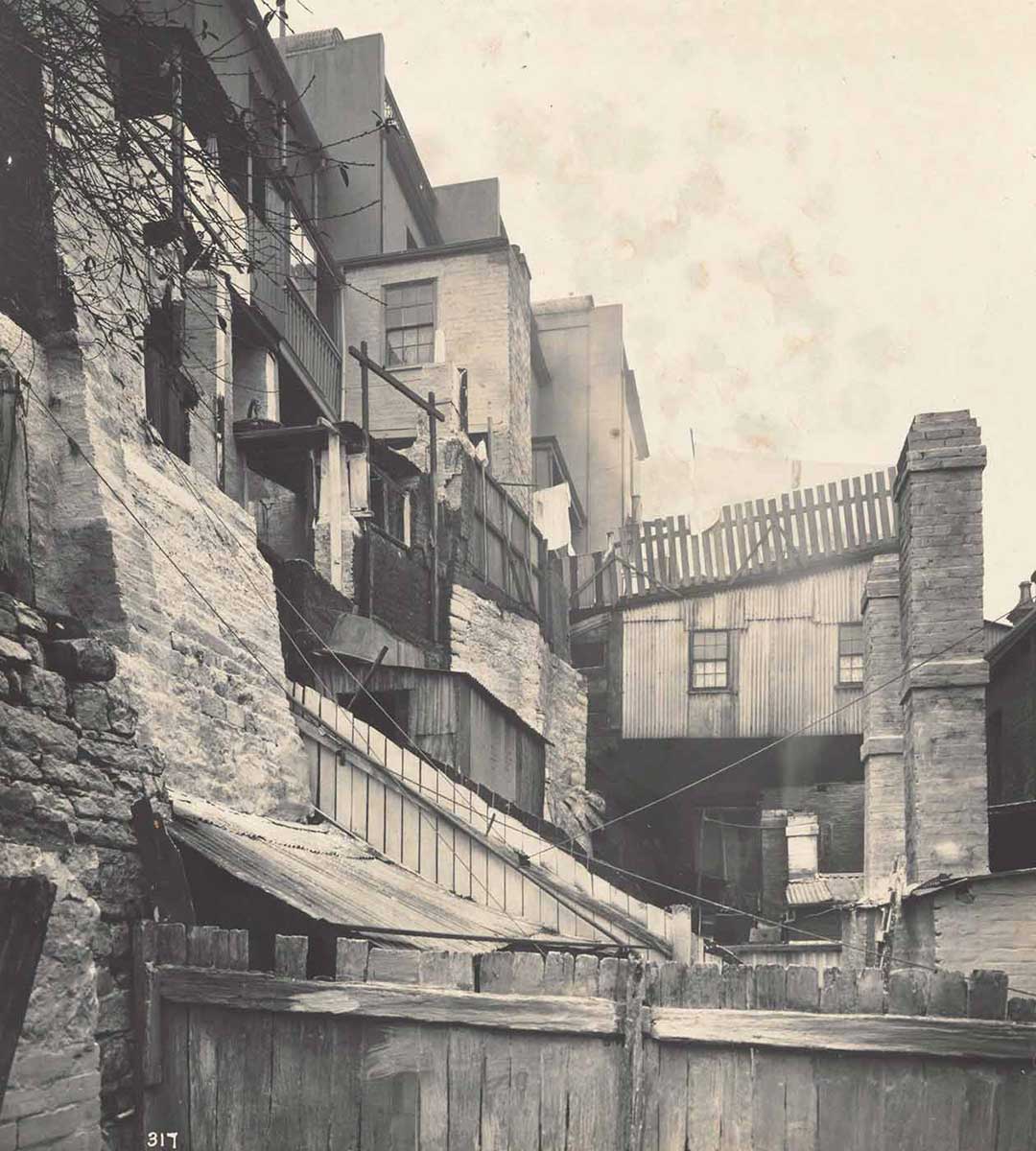

The colonial and city governments instituted a three-pronged approach to controlling the disease in Australia: transporting infected individuals and anyone they may have had contact with to the quarantine station at North Head; intensive cleaning and, in some cases, demolition of sections of the inner city and dock area; and a rat extermination program.

Initially the quarantine period was 10 days but this was eventually reduced to five. In the first nine months of 1900, 1,759 people were quarantined. Of these only 263 were confirmed cases.

In February 1900, cleaning of infected neighbourhoods began under the direction of the newly formed Plague Department. Lime, carbolic water and lime chloride were used to disinfect houses and all waste, including garbage, manure and stable bedding, was removed and burned.

In March the city council began organising teams to exterminate the rat population. The government paid two pence per rat delivered to an incinerator on Bathurst Street.

Eventually, more than 108,000 rats were killed by government employees, although the number killed by private individuals using poison provided by the authorities may have exceeded that number.

Australian contribution to science

During the Hong Kong epidemic in 1894, the French and Japanese epidemiologists Alexander Yersin and Kitasato Shibasaburo individually discovered the pathogen that causes the disease. Another French epidemiologist, Paul-Louis Simond, then proved during the 1896 plague outbreak in Bombay that fleas (Xenopsylla cheopsis) could act as vectors for transmission between rats.

However, this theory was not widely accepted by the medical community until the chief of the New South Wales Board of Health, John Ashburton Thompson, isolated the Y pestis bacterium in fleas on dead rats captured in Sydney. Ashburton Thompson’s reports were ‘models of cogent reasoning’ and his experiments were instrumental in changing public health methods around the world to combat bubonic plague.

Aftermath of the bubonic plague

Bubonic plague continued to reappear annually in Sydney until 1910, with smaller numbers of cases also reported in north Queensland, Melbourne, Adelaide and Fremantle. In total, 1,371 cases were reported with 535 deaths across Australia.

Because of its coordinated and scientific approach to plague eradication, Australia fared better than many other parts of the world. Australia’s example became instrumental in proving the importance of public health departments and modern, sanitary, urban planning principles.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

You may also like

References

Peter Curson, Plague in Sydney: The Anatomy of an Epidemic, New South Wales University Press, Kensington, NSW, 1989.

Rod and Wendy Gow, Plague Epidemic in Australia: Sydney and Interstate, Cundletown, NSW, 2006.