Just before the end of the Boer War, lieutenants Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant and Peter Handcock were executed by firing squad for murdering 12 Boer prisoners of war.

That they committed the crimes is beyond doubt. However, the controversy surrounding their trial and execution led to Morant being considered a folk hero by the Australian public.

The Bulletin, 19 April 1902:

Why should stern justice be meted out to us whilst others go scot free? Why should the English officer who is a Bushveldt Buccaneer be a gentleman and a soldier whilst we Australians are scallywags only fit for a firing party?

Boer War

Throughout the 19th century, Britain unwillingly shared its dominion of southern Africa with Dutch settlers known as Boers. Tension between the groups was evident from their earliest occupation but was heightened between the 1860s and the 1880s by the discovery of diamonds and gold in the Boer-occupied regions.

Gold made this area the wealthiest in southern Africa and Britain wanted control of the resource. The Boers refused to agree. A British raid on Boer territory ultimately led to the Boers declaring war on Britain in October 1899.

The war lasted for two and a half years. In the first three months, the Boers had the advantage and besieged the cities of Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking.

From December 1899, the British brought in large numbers of troops and mounted a successful counter-offensive. Eventually more than 500,000 soldiers fought for the British against only 50,000 Boers. The vast numerical difference led the Boers to employ irregular, guerrilla tactics and eventually the British followed suit.

During the guerrilla phase of the war, the British Army, commanded by Lord Kitchener, sought to cut the Boer commandos off from their food supplies and the support of their families.

This meant destroying Boer farms and interning civilians in concentration camps. There, weakened by malnutrition, 28,000 Boer women and children and at least 20,000 Africans died of disease. The strategy was brutally effective and the Boers surrendered in May 1902.

Australia and the Boer War

As part of the British Empire, the Australian colonies and later the Commonwealth of Australia, provided volunteer troops for the war. As many as 16,000 Australians fought in the Boer War. Almost 600 died.

Australians at home initially supported the war but became disenchanted as the conflict dragged on, especially as the suffering of the Boer civilians became known.

Breaker Morant

Edwin Henry Murrant was born in England but moved to Australia around 1883 at the age of 19. There he changed his name to Harry Harbord Morant and reinvented his past.

He acquired a reputation as a horse-breaker, drover and womaniser and from 1891 contributed bush ballads to the Bulletin as ‘the Breaker’. When the Boer War broke out he enlisted in Adelaide and arrived in South Africa in February 1900.

Morant spent nearly a year serving in South Africa before sailing for England where he befriended Captain Percy Hunt, who had also served in the war. Morant joined Hunt in returning to South Africa in March 1901.

Bushveldt Carbineers

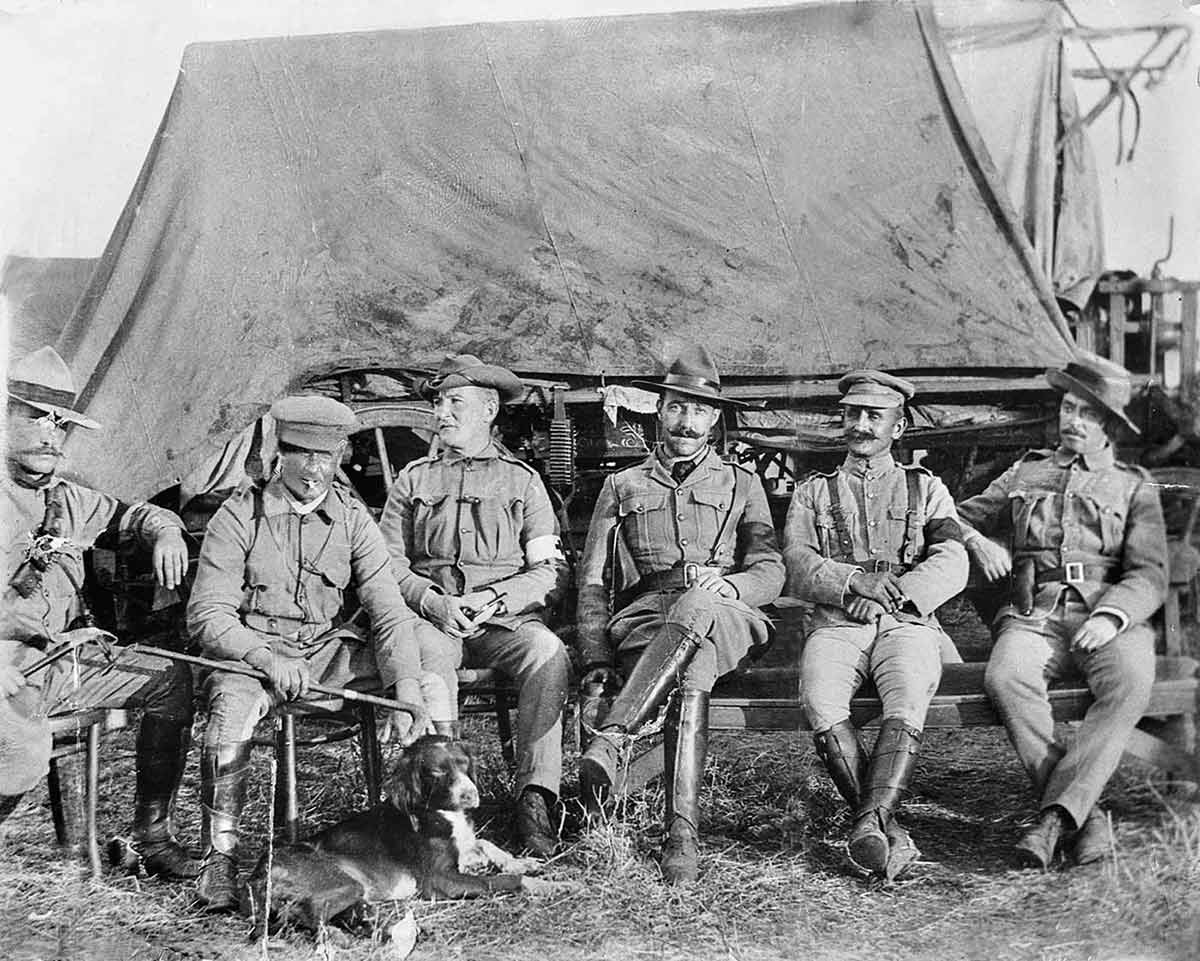

By 1901 the British had started forming irregular units to counter the Boers’ guerrilla tactics. One of these was the Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC), which included many Australians.

Hunt and Morant joined the Bushveldt Carbineers and Morant was commissioned as a lieutenant. They were soon posted to Fort Edward in the remote Spelonken district in the northern Transvaal where the fighting was especially bitter.

On patrol in August 1901 Hunt was killed by a group of Boers and his body mutilated. Morant assumed command of Hunt’s detachment and pursued the Boers who had killed his friend. The patrol captured one of their number, a man called Visser, and Morant had him shot.

Returning to Fort Edward, Morant ordered the execution of eight Boers who approached the base wishing to surrender. A similar incident took place shortly afterwards in which Morant and two others killed another three Boers.

A passing missionary of German extraction, Reverend Heese, was also shot shortly after leaving Fort Edward. It was alleged that Morant ordered his subordinate, Lieutenant Peter Handcock, to do this because Heese might have reported the shooting of prisoners.

Morant, Handcock and four other Bushveldt Carbineer officers were arrested on 7 September 1901 and in October were charged with murder.

Trial and execution

Major JF Thomas, a solicitor from Tenterfield in NSW before he served in the Boer War, was ordered at short notice to represent the accused. The trial began on 17 January 1902.

Central to Thomas’s defence was that the officers were acting on the orders of their superiors, right up to Lord Kitchener, to take no prisoners. However, Thomas was unable to substantiate that such an order had been given.

Morant, along with the Australian-born officers Handcock and Lieutenant George Witton, were convicted of murdering 12 prisoners but found not guilty of murdering Heese.

With Kitchener’s approval, Handcock and Morant were executed by firing squad in Pretoria on 27 February 1902. Witton was given a life sentence. He was released four years later.

Controversy and legacy

The execution of Morant and Handcock has divided public opinion. At the time, Australians were simultaneously shocked that Australian officers could commit such crimes and that Britain would execute them without consulting the Australian government.

The Bulletin published editorials defending Morant and a biography appeared shortly after his death. Many people felt the two Australians were seen as expendable because they were ‘colonials’.

Speculation arose as to why Kitchener had sanctioned the trial and hasty execution of officers who were carrying out what had become a common practice on both sides. Kitchener’s imagined motives included appeasing the German government over the death of Heese, placating the Boers ahead of a treaty, and deflecting attention from the deaths of Boer civilians in the concentration camps.

Kitchener, the ruthless aristocrat and Morant, the charismatic larrikin, seemed to embody fundamental differences between Britain and Australia, especially as the latter sought to establish its national identity in the wake of Federation, which took place midway through the war.

Despite the fact that he was a murderer, Morant became a folk hero in the manner of Ned Kelly. A succession of books published on his life throughout the 20th century and the production of a successful film, Breaker Morant, in 1979, reignited public debate and ensured that Morant remained in the public consciousness.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Australia and the Boer War, Australian War Memorial

Peter Handcock, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Breaker Morant, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Nick Bleszynski, Shoot Straight, You Bastards!, Random House, Sydney, 2002.

Kit Denton, For Queen and Commonwealth, Time-Life Books Australia, Sydney, 1987.

Thomas Pakenham, The Boer War, Abacus, London, 1992.

Craig Stockings (ed), Zombie Myths of Australian Military History, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2010.

George Witton, Scapegoats of the Empire, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1982.