The 1932–33 Ashes series is the most controversial in the history of Australian–English Test cricket.

The English team, desperate to contain Australian batsman Don Bradman and win back the Ashes, adopted a controversial strategy. Technically known as ‘fast leg theory’, it was better known as ‘bodyline’.

It came close to turning a summer of cricket into a diplomatic row.

Bill Woodfull, Australian captain, 1933:

There are two teams out there; one is trying to play cricket and the other is not.

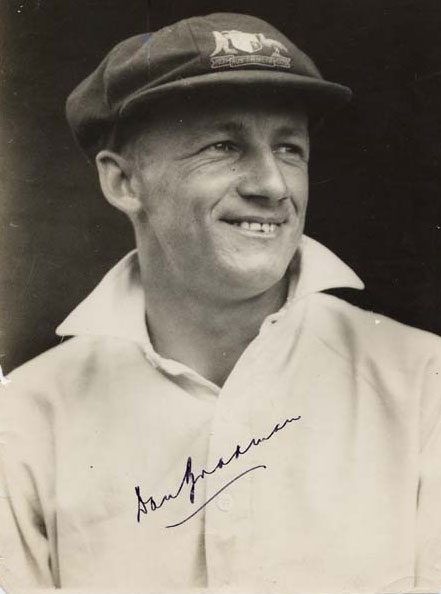

Bradman problem

The 1932–33 Ashes series is the most controversial in the history of Australian-English Test cricket. The English team, desperate to contain Australian batsman Don Bradman and win back the Ashes, adopted a controversial strategy. Technically known as ‘fast leg theory’, it was better known as ‘Bodyline’.

The Great Depression was weighing heavily on Australians. Unemployment was rising and austerity measures, recommended to the Australian Government by British economists, were widely resented.

During Australia’s tour of England in 1930, the young Don Bradman dominated the English bowlers. During the Test series, Bradman scored 974 runs (an average of 139.14) including one single century, two doubles and a triple (334), which broke the world Test batting record. This caused significant disquiet for the English cricketing community but elation in Australia where Bradman returned a hero.

Douglas Jardine

In preparing for their 1932 tour to Australia, England sought a way to stifle Bradman’s scoring. Their captain, Douglas Jardine, developed an approach in which the ball was bowled fast and short, rising up to the batsman's body while fielders hovered close to the leg side.

The strategy was intended to intimidate the batsman, stifle the swing of his bat and force him to play defensively. But it also posed a genuine physical threat.

The relationship between Jardine and Australian cricket fans was already tense. During the 1928–29 tour to Australia he was perceived as supercilious and rude. His air of upper-class superiority rankled with the Australian crowds.

As captain for the 1932–33 series, Jardine made no efforts to remedy the situation, was uncooperative in press interviews and didn’t provide team details before matches. While Jardine’s character exacerbated the situation, his tactics had the backing of the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC).

The Test series began in Sydney with England winning the match. Bradman was absent due to illness. Australia levelled the score in Melbourne. Then during the third Test in Adelaide, the English captain turned to Bodyline tactics.

The already hostile crowd was furious and when one delivery struck Australian captain Bill Woodfull just above the heart it was feared a riot would start. Tempers flared on the field and in the stands, and while Woodfull maintained a diplomatic stance in public, in private he too was furious.

Angry words

A key aspect of Australian frustration was that the English tactics seemed to go against all that was valued in cricket: fair play, ethical conduct and a shared cultural understanding of behaviour. In response to the danger faced by the players, the Australian Board of Control for International Cricket sent a tersely worded telegram to the MCC on 18 January 1933:

Body-line bowling has assumed such proportions as to menace the best interests of the game, making protection of the body by the batsmen the main consideration.

This is causing intensely bitter feeling between the players as well as injury. In our opinion it is unsportsmanlike.

Unless stopped at once it is likely to upset the friendly relations existing between Australia and England.

The English administrators did not appreciate their players being accused of unsportsmanlike conduct. Not having witnessed the barrage of body blows, they felt that the Australian side was making excuses. The MCC responded sternly on 23 January:

We, Marylebone Cricket Club, deplore your cable. We deprecate your opinion that there has been unsportsmanlike play…

We hope the situation is not now as serious as your cable would seem to indicate, but if it is such as to jeopardize the good relations between English and Australian cricketers and you consider it desirable to cancel remainder of programme we would consent, but with great reluctance.

For a while it seemed that cricket would strain diplomatic relations between Australia and England. After intervention from the Australian Prime Minister Joseph Lyons, the Australian Board of Control withdrew its charge of unsportsmanlike behaviour and the final tests were played. England won the series 4–1 and reclaimed the Ashes.

The impact of England’s bodyline tactics extended beyond the cricket pitch. Struggling with ongoing hardship during the Depression, Australians saw the aggressive tactics of the English team as representative of England’s wider attitude to the country.

While riots and diplomatic rows were averted, the series challenged not only a shared understanding of cricket but tested Australia’s changing relationship with England and empire.

In our collection

References

Information about the Bodyline Series, State Library of NSW

David Frith, Bodyline Autopsy: The Full Story of the Most Sensational Test Cricket Series: Australia v England 1932–33, ABC Books for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Sydney, 2002.

Ric Sissons and Brian Stoddart, Cricket and Empire: The 1932–33 Bodyline Tour of Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1984.