On ‘Black Thursday’, 6 February 1851, European settlers in Victoria faced their first catastrophic bushfires, which burnt a quarter of the colony.

James Fenton, in Bush Life in Tasmania Fifty Years Ago, recalled how the Victorian fires appeared to an observer on the north coast of Tasmania:

Early in the afternoon clouds came rolling over the heavens, obscuring the light of the sun in a most ominous and mysterious manner. There was a lurid glare in the sky, mixed with dense columns of blackest cloud-banks in the distance, which stole gradually upwards from the horizon until the sun became entirely obscured.

Prelude to the Victorian bushfires

Permanent European settlement in Victoria began at Portland in 1834, and at Melbourne in 1835.

In February 1851, only a few months before the area achieved its status as a colony independent of New South Wales, the settlers confronted their first cataclysmic bushfires.

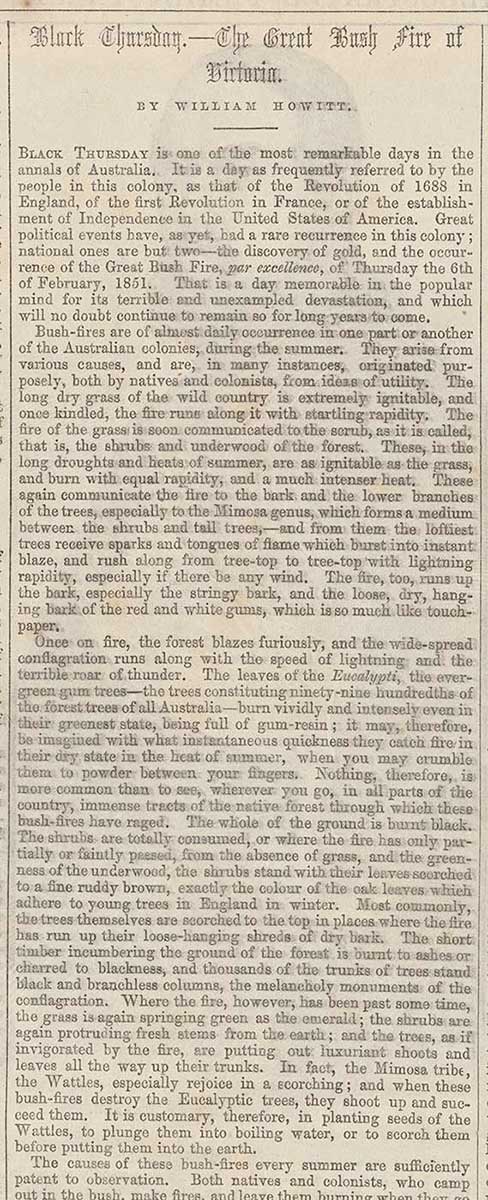

The fires followed a period of unusual and erratic weather. 1848 had seen heavy rainfall, followed by drought.

Then high temperatures in the summer of 1848–49 led to significant bushfire risk. The following winter Europeans saw snow for the first time in Melbourne, followed by deluges and floods.

High rainfall in 1849 encouraged the build-up of vegetation throughout the colony, only for further drought in 1850 to dry it out.

The following summer of 1851 was long and hot. For weeks before Black Thursday, bushfires raged uncontrolled in the Plenty Ranges, north-east of Melbourne.

There were also fires on Mount Macedon to the north and in the Pyrenees to the west. A newspaper proposed a ban on smoking on the road to Sydney, to minimise the risk of starting new fires.

Black Thursday

Thursday 6 February 1851, the day which would become known as ‘Black Thursday’, was the hottest day the European settlers could remember. It was 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43.3 degrees Celsius) in the shade.

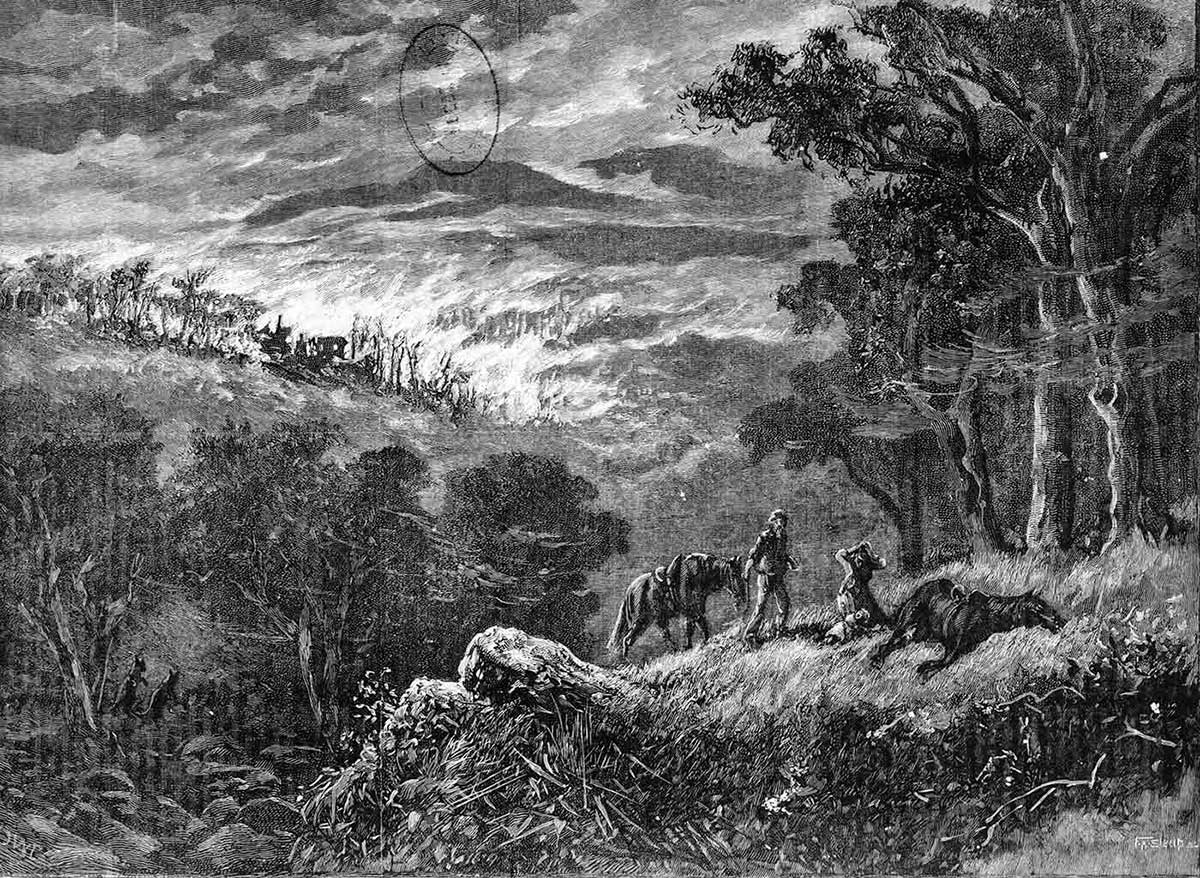

It was an oppressive day. A strong north wind was driving a ring of fires that were already burning, and new fires broke out towards Melbourne. Eyewitness and author Rolf Boldrewood wrote: ‘The whole colony of Victoria was on fire at the same time, from the western coast to the eastern range of the Australian Alps’.

The dark and lurid sky reminded Boldrewood of the destruction of Pompeii, while others (he claimed) thought it was the end of the world. Most dangerous was the speed with which ‘the flame-wave rolled in over grass and forest from the north’.

In some areas the drought had left grass too thin to form a major hazard, but elsewhere flames leapt from treetop to treetop, and windblown fragments of burning bark drove the fires onward.

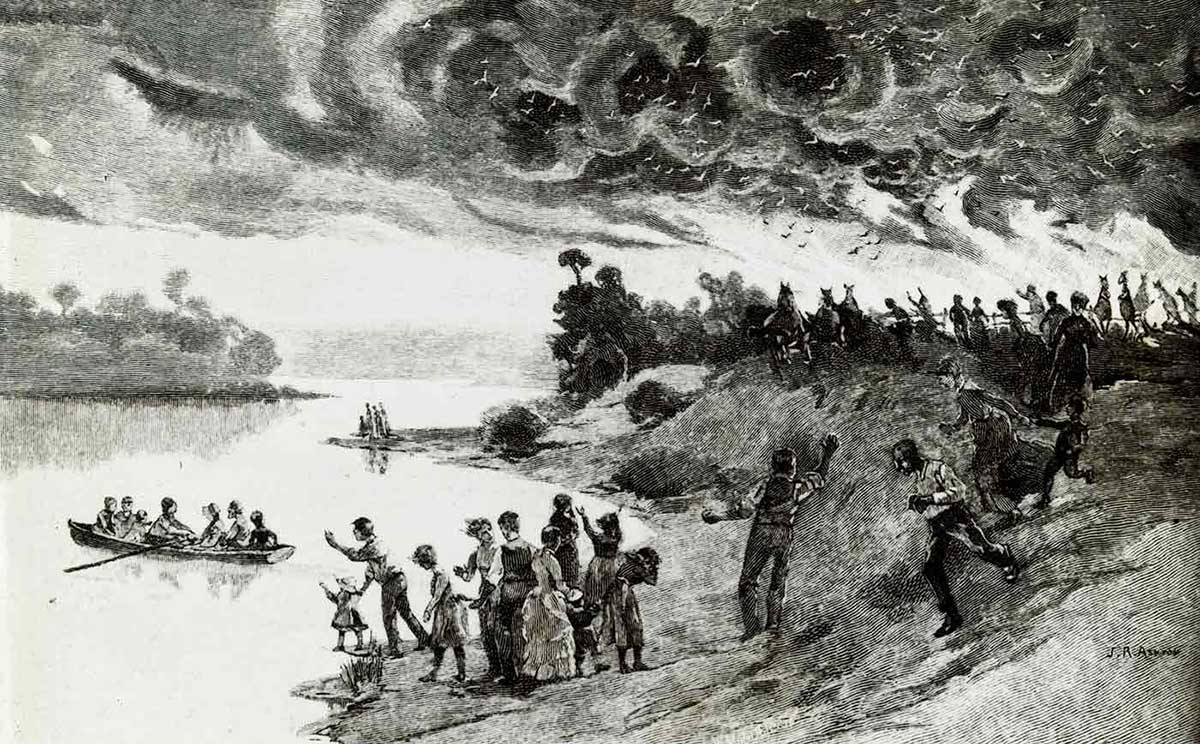

In total, about five million hectares burnt, a quarter of Victoria. On the same day, much of western Tasmania, only recently settled by Europeans, was also burnt.

Counting the losses

Remarkably, there were only 12 known deaths – owing no doubt to the relatively small population in 1851.

Some who had lost their houses managed to survive in the bush or in creeks. And at Westernport a schoolhouse with 19 children and a teacher inside was saved at considerable risk.

But not everyone was so lucky. Bridget M’Lelland, and her five young children, died at Diamond Creek. Her husband, Richard, suffered severe burns attempting to rescue one of the children.

At the inquest Alexander Miller, a shepherd working for the M’Lellands, reported that there had been a fire burning on mountains 15 kilometres away for weeks.

On Black Thursday he had taken a mob of sheep down to the creek to drink, only to find that the fire had now jumped the creek, and was moving rapidly towards the station.

Hampered by smoke, he ran to the house to raise the alarm, but it was too late. The family had scattered from the hut, but the fire cut them off from the creek, their only possible refuge. Miller survived by sheltering in the creek, where he also found Richard M’Lelland.

In the hills west of Geelong, a man helping fight a fire disappeared. His body was later found ‘burnt to a cinder’. Another man who perished was with a group burning stubble to form a firebreak when they were caught out by a wind change. His companions scattered, but he went the wrong way.

Domesticated animals and wildlife suffered terribly. It was estimated that one million sheep and thousands of cattle were lost.

The Melbourne Argus callously noted that ‘pigs and dogs running loose were burned to death – birds were dropping down off the trees before the fire in all directions – oppossums, kangaroos, and all sorts of beasts can be had to-day ready roasted all over the bush’.

Bushfires and gold

Apart from the dry conditions, the fires probably had various causes. One might have been lightning strikes, but historian Tom Griffiths has also raised the possibility that some of the fires may have been caused by prospectors seeking to make the search for gold easier.

Black Thursday occured during a time when many were looking for gold. Although gold was officially ‘discovered’ in Victoria later in 1851, there had already been scattered discoveries in the 1840s.

By 1851 there were expeditions looking for gold in several parts of the colony, including the Pyrenees and Plenty ranges. Dense vegetation was a real problem for prospectors looking for surface gold, and so they often burnt it back.

At the very least, the huge areas burned in February 1851 may have contributed to the major gold discoveries which soon followed.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

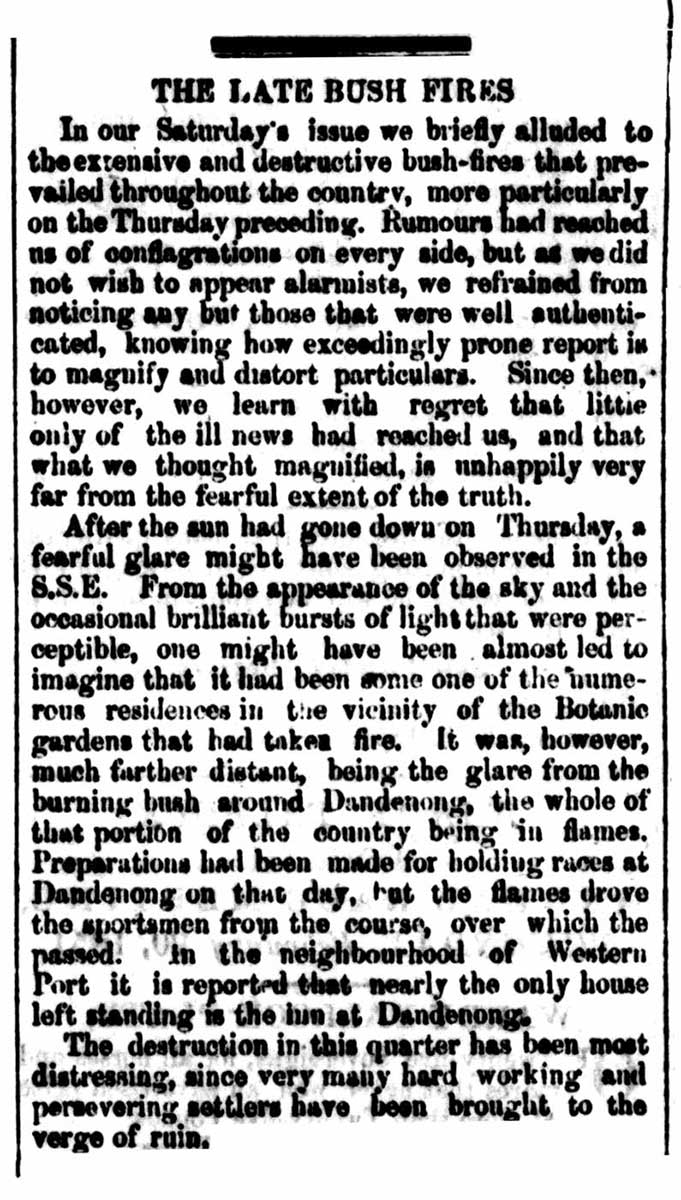

‘The late bushfires’, The Argus (Melbourne), 10 February 1851, p. 2

Rolf Boldrewood, Old Melbourne Memories (2nd ed.), Macmillan, London, 1896, pp. 118–21

Stephen J Pyne, Burning Bush: A Fire History of Australia, Henry Holt, New York, 1991.

Douglas Wilkie, ‘Earth, wind, fire, water – gold: Bushfires and the origins of the Victorian gold rush’, History Australia, vol. 10, no. 2, 2013, pp. 95–113.