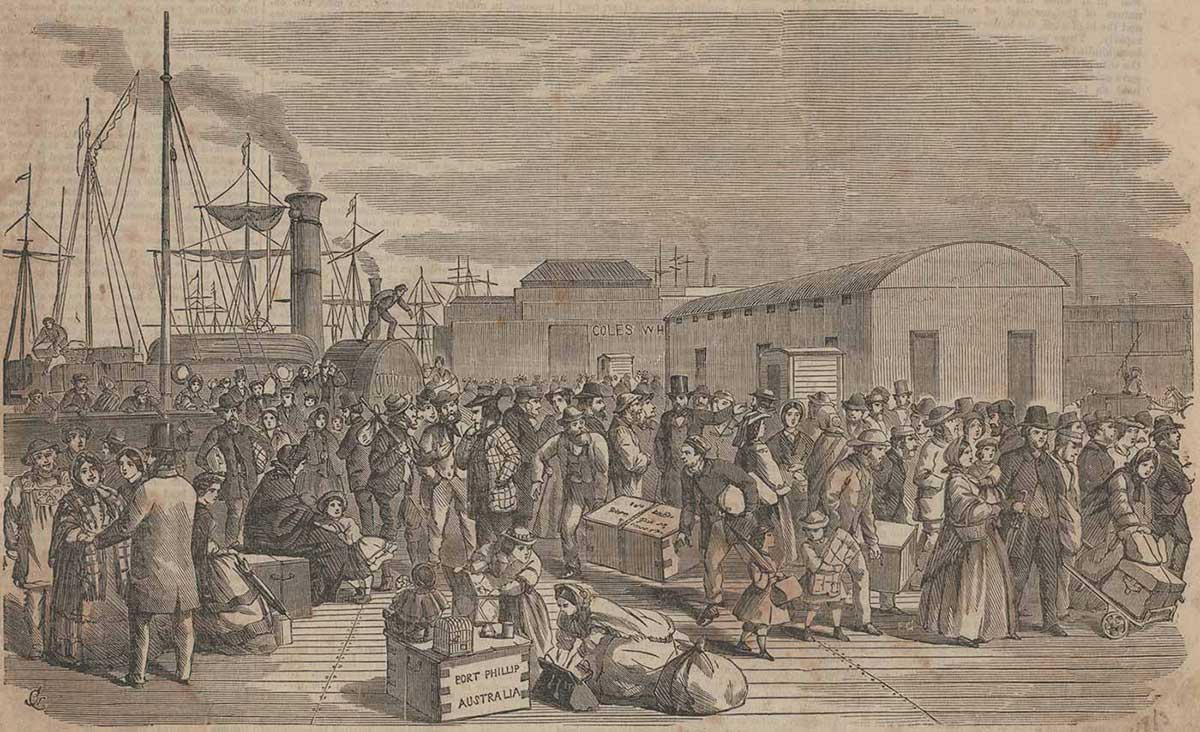

From 1831 the British and Australian colonial governments subsidised or paid for thousands of migrants to move to Australia.

Henry Parkes, letter to his sister, 6 December 1838:

I have been to the Government emigration office to ascertain what assistance they afford to mechanics wishing to emigrate, and we can have a free passage, being young and having no children.

Migration to Australia

The numbers of convicts sent to Australia increased sharply in the 1820s. In New South Wales the convict proportion of the population increased from 30 per cent in 1805 to 46 per cent in 1828.

At the same time, Australia was an attractive destination for the relatively wealthy of Britain. With the crossing of the Blue Mountains, huge tracts of land became available, and the wool industry thrived. Wealthy migrants could hope to become members of the colonial upper classes.

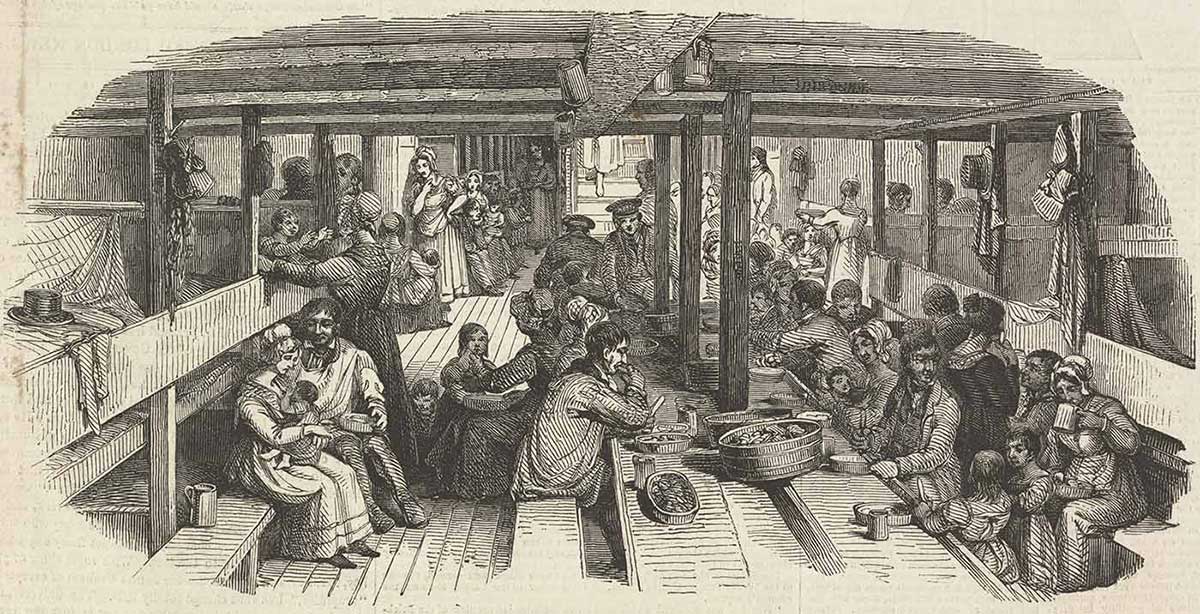

But the 19th century was also a period of mass emigration from Europe, and from Britain in particular. Between 1815 and 1840, one million emigrants left Britain. Most, however, went across the Atlantic to the United States and Canada. The much longer passage to Australia, on the other side of the world, was too expensive for many poor migrants.

Britain encourages migration

Governments in both Britain and Australia wanted to increase the number of free migrants.

In Britain the period after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 was one of social upheaval and widespread unemployment. Authorities worried that a rising population was outstripping resources, and that the disaffected working classes might pose a threat to social stability.

In both Ireland and Scotland small farmers were losing their land. Irish farmers with small plots were forced to rely on potatoes, with dire consequences if the crop failed. For many, emigration to either the Americas or Australia was the answer. British governments saw this as the solution to the excess supply of able-bodied workers.

It was also a cost-effective solution. Parishes in Britain had to levy rates to support the very poor. If the poor migrated, they would cease to be a burden, and ultimately they would create a market for British goods.

In the 1820s a scheme sought to send the poor to Canada. In 1832 the Land and Emigration Commission was set up under the Colonial Office to do the same for Australia.

Over the following decades the commission organised voyages for hundreds of thousands of emigrants, and reduced the death toll on the voyage from five per cent to 0.5 per cent.

The need for migrants in Australia

The Australian colonies particularly wanted skilled labourers and single women. Labourers were needed especially to work in the interior, though the large land grants which wealthy settlers had acquired encouraged grazing rather than agriculture. Single women could help address the problem that there were many more men than women in the colonies.

But not everybody in Australia favoured assisted migration. Some moralisers feared that the colonies would be a dumping ground for the dregs of British society. Presbyterian minister John Dunmore Lang claimed that female migrants had made Sydney ‘a sink of prostitution’.

No doubt some women did find employment as sex workers, but New South Wales Governor Richard Bourke had to point out to the Colonial Office that there was limited demand for governesses, ladies’ maids, even milliners and dressmakers.

Most of all, the colony needed women who could go into the country and be of practical assistance on farms.

In the early 1830s migrants were given an assisted passage, but incurred a debt which they had to repay over time as they found work.

By the late 1830s (1836 in New South Wales) the colonial governments had changed this system. They now provided free passage to migrants without expecting the debt to be repaid. The schemes were funded by the sale of land, generally at five shillings per acre.

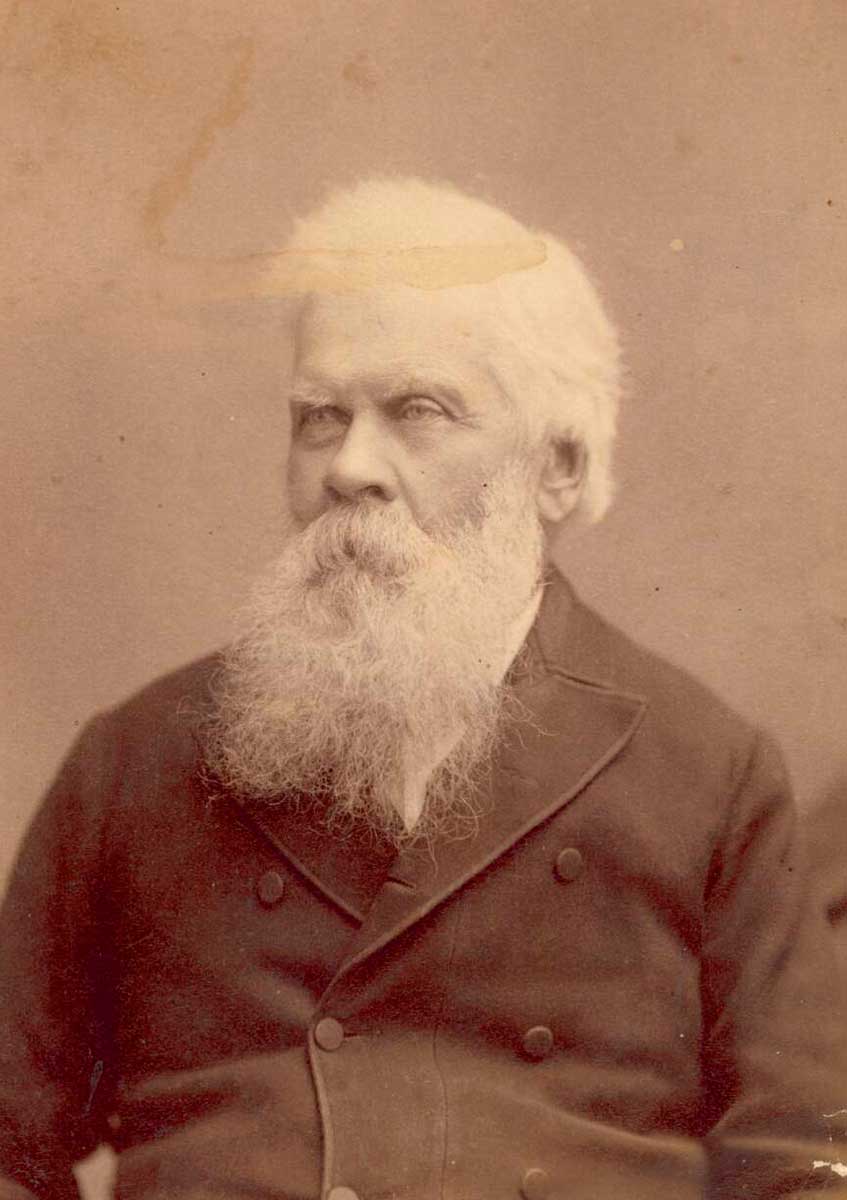

Henry Parkes

In 1839 Henry Parkes and his wife, Clarinda, were two of the thousands of assisted migrants. Parkes would later be Premier of New South Wales and one of the fathers of Federation.

In England he had trouble making a living as an ivory turner. Like many migrants, the couple arrived in Australia with almost no money, and had to sell possessions to survive.

Eventually Henry found work, first on a wealthy estate at Penrith, and then in a series of other jobs.

While in England, Parkes had been optimistic about the riches awaiting migrants to Australia. Two years later he reported more soberly that hundreds of migrants were starving in the streets of Sydney.

On arrival, the assisted migrants were allowed to live on board ship for 10 days while they looked for work. After that they had to fend for themselves. One woman, turned off her ship and, by her account, contemplating suicide, was accused of being drunk and placed in the stocks for an hour.

Assisted migration to Australia

Nevertheless, overall the assisted migration schemes were very successful. Between 1832 and 1850, 127,000 assisted migrants came to Australia, representing about 70 per cent of all immigrants in that period.

Assisted migration continued on an even larger scale after the discovery of gold in 1851. In the 1850s there were 230,000 assisted migrants, representing about 50 per cent of all migrants. Most came from the United Kingdom (including Ireland), though there were smaller groups (from Germany, for example).

To different degrees in the various colonies, assisted migration continued for the rest of the century. It was a significant factor in increasing the European population in Australia.

In our collection

Defining Moments in Australian History 21 Sep 2016

Defining Moments in postwar immigration panel discussion

References

Robert Madgwick, Immigration into Eastern Australia, 1788–1851, Sydney, Sydney University Press, 1969.

Geoffrey Sherington, Australia’s Immigrants 1788–1988, 2nd ed., Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 1990.

Robyn Haines and Ralph Shlomowitz, ‘Immigration from the United Kingdom to colonial Australia: A statistical analysis’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 16, no. 34, 1992, pp. 43–52.