William Dampier was an explorer, naturalist, author, hydrographer and pirate.

He was the first Englishman to chart part of the Australian coastline, and the first European to undertake a scientific study of its landscape, seas, plants and animals.

Though he intended to circumnavigate the entire continent, he was prevented from doing so by the unseaworthiness of his ship.

Letter from Dampier to the Earl of Pembroke, President of the Privy Council:

The world is apt to judge of everything by the success; and whoever has ill fortune will hardly be allow’d a good name.

An adventurous life

William Dampier was born to tenant farmers in a village in Somerset, England in August 1651. He went to sea at 17, and five years later joined the Royal Navy, fighting in the Third Anglo–Dutch War of 1672–74.

He left the navy shortly afterwards and sailed to the West Indies, where he worked on a plantation. When England went to war with Spain, Dampier tried to make his fortune by becoming a privateer, which was effectively a state-sanctioned pirate.

Nations at war often bolstered their naval strength by authorising pirates to attack enemy merchant ships. This provided pirates with the opportunity to enjoy their plunder without fear of retribution.

In 1678 Dampier returned to England and married his fiance, Judith, in Dorset. The following year he went to sea again, becoming only the third Englishman in history to sail around the globe. It was a voyage that lasted 12 years, involved several ships and long periods ashore.

First visit to Australia

After years of buccaneering around Central America, in 1685 Dampier joined a privateering vessel, the Cygnet. He spent the next three years in the Cygnet as it sailed the Pacific in search of vulnerable vessels.

In January 1688 the Cygnet arrived at King Sound, near present-day Broome, where the captain beached the ship for urgent repairs.

The crew were the first Britons to set foot on the Australian mainland – then known as New Holland, the name Dutch explorer Abel Tasman had given it in 1644 – 82 years before Lieutenant James Cook arrived at Botany Bay. The party remained for two months and established friendly relations with the local Aboriginal people, most likely the Bardi people.

Man of letters

Dampier returned to England in 1691. Six years later, he published an account of his travels, titled A New Voyage Round the World.

It was an immediate success, owing to Dampier’s brisk writing style, his obvious enthusiasm and his accurate observations. The book went through multiple editions, was widely translated and helped establish travel writing as a popular genre.

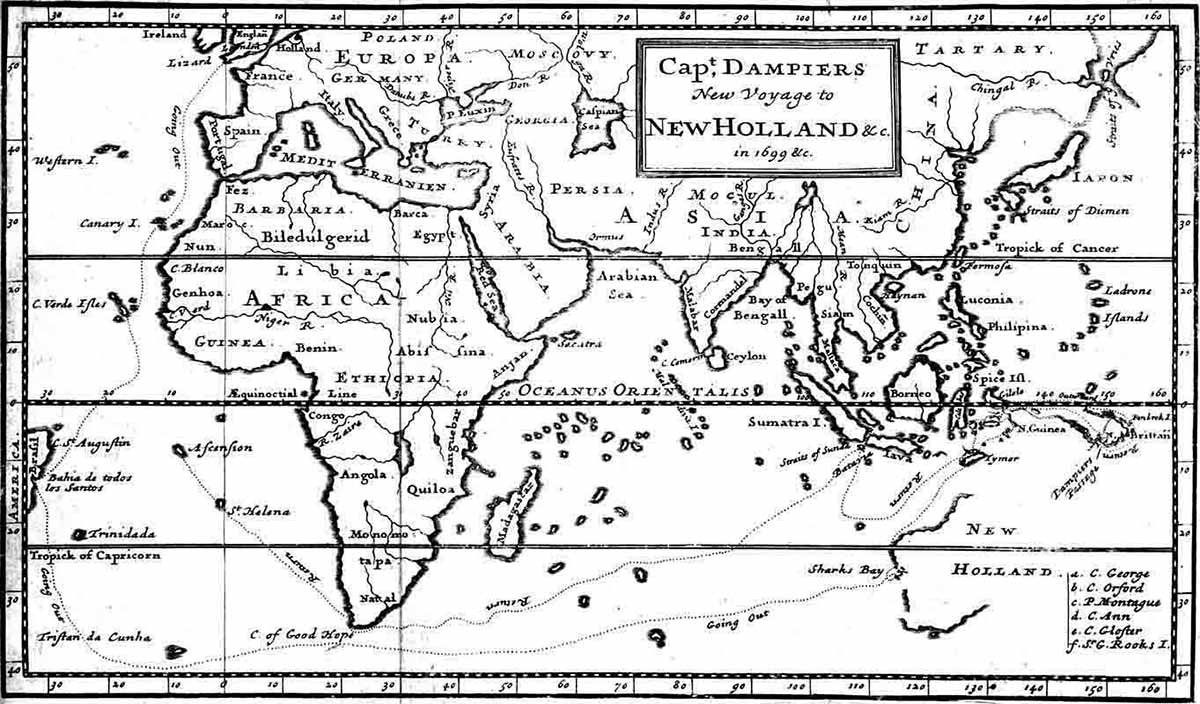

It also established Dampier as an expert on the East Indies (present-day Indonesia), and in 1698 the Admiralty commissioned him to return to New Holland to explore and chart its coasts. The underfunded Admiralty could only spare HMS Roebuck, a 290-ton vessel that was not seaworthy enough for such a long voyage.

Voyage to Australia

Dampier had intended to travel westwards to New Holland via Cape Horn (the tip of South America), but delays in fitting out the Roebuck meant he arrived in South America in winter, when it was too dangerous to attempt to round the Horn.

Instead he headed east and entered the Indian Ocean via the Cape of Good Hope (the tip of Africa), which meant it was the west coast of New Holland that he encountered, not the east.

The west coast had already been mapped by the Dutch, most notably by Abel Tasman, whose chart Dampier used.

Leadership

Though a capable navigator, Dampier was not a good leader of men.

Soon after the Roebuck left England, he had his second in command, Lieutenant George Fisher, caned and clapped in irons following a heated argument – a punishment inappropriate for an officer. Dampier then put him ashore in Brazil.

It is likely that Fisher and the other officers resented having a civilian in command, particularly one with a buccaneering background.

Arrival at Shark Bay

Dampier headed for Dirk Hartog Island at the entrance to Shark Bay, near present-day Carnarvon in Western Australia. He made landfall on 6 August 1699.

From there, he spent about three months charting the roughly 1400 kilometres of coast between Shark Bay and Lagrange Bay, south of Broome. He stopped on several occasions, collecting biological specimens, taking careful scientific notes and keeping a meticulous diary. He was unimpressed with the sandy, dry and barren coast.

The land … is low but seemingly barricaded with a long chain of sandhills to the sea, that lets nothing be seen of what is farther within land … The land by the sea for about 5 or 600 yards is a dry sandy soil, bearing only shrubs and bushes of divers sorts.

On 5 September Dampier abandoned his exploration of New Holland when he began to run out of water. He went to Timor to replenish his stores and from there charted the north coast of New Guinea. He then named and circumnavigated New Britain, proving it was a separate island.

Return to England

Dampier intended to return to New Holland and visit the east coast. But the Roebuck was now leaking badly and his crew’s morale was running low, so he decided to return to England.

The Roebuck finally sank at Ascension Island in the mid-Atlantic. Everyone aboard survived, and Dampier was able to rescue his notes, diary and some specimens before the ship went down.

Upon his return to England in 1701, Dampier was court-martialled for his mistreatment of Fisher. He was found guilty and had his entire salary for the expedition docked.

However, the expedition provided Dampier with the material for his next book, A Voyage to New Holland, which was published in two parts in 1703 and 1709.

As with his first book, it sold well, in part because it contained engravings of birds, fish and plants drawn by drafter James Brand. The drawings are not very accurate, but they are the first known images of Australian flora and fauna made by a European.

Despite its success, A Voyage to New Holland, like all of Dampier’s books, made much more money for its unscrupulous publisher than it did for its author.

Dampier’s subsequent life

In 1703, with England fighting the War of the Spanish Succession, Dampier returned to privateering. His first trip as commander of the pirate ship St George was a failure.

On his return to England in 1707 he joined another privateer as navigator, and again circumnavigated the world, returning to England four years later. Yet again, the trip brought him little reward.

In 1708 Dampier left on his final major voyage. He circumnavigated the globe again on a series of ships, and the crew amassed a small fortune in plunder. However, less than four years later he died in London, with his estate in serious debt.

Dampier’s legacy

Dampier’s contribution to the exploration of Australia was slight, but he was the first European to conduct a detailed scientific study of the continent’s terrain, seas and biology. He was also the first person to circumnavigate the world three times.

Dampier’s books were read with interest by subsequent explorers and naturalists, including James Cook and Matthew Flinders, as well as Alexander von Humboldt and Charles Darwin.

References

William Dampier, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Leslie R Marchant, An Island unto Itself: William Dampier and New Holland, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, 1988.

Diana and Michael Preston, A Pirate of Exquisite Mind: The Life of William Dampier, Walker & Company, New York, 2004.

Joseph C Shipman, William Dampier: Seaman, Scientist, University of Kansas Libraries, Lawrence, Kansas, 1962.