In 1890 unionists and employer groups faced off over wages and conditions against the background of a deep economic depression across Australia.

The maritime and shearers’ strikes of 1890 and 1891 were the largest, most violent industrial actions seen in Australia, but with the government and police supporting employers both strikes failed to fulfill the unions’ objectives.

Activists realised that change for working people would only come about through combined union and political action. This led to the creation of the Australian Labor Party.

Prime Minister Ben Chifley, 1949:

I try to think of the Labour movement, not as putting an extra six pence in somebody’s pocket, or making someone Prime Minister or Premier, but as a movement bringing something better to the people … We have a great objective – the light on the hill – which we aim to reach by working for the betterment of mankind not only here but anywhere we may give a helping hand.

Depression

Between 1890 and 1893, a severe economic depression gripped Australia.

Wool exports had boomed in the decades prior to the depression and Australians were enjoying some of the highest incomes in the world. Throughout the 1880s, this prosperity led to an increase in speculative foreign investment in the wool industry.

However, by the end of the decade a stagnating global economy had made international investors wary of investing in the Australian economy. This led to many financiers deciding to withdraw funds which created a run on financial institutions that in turn called in loans that businessmen and pastoralists weren’t able to repay.

The Commercial Bank of Australia, one of the country’s largest, shut down in April 1893 and a dozen other banks quickly followed. Thousands of small and large investors were ruined.

Strikes

It was against this backdrop that a series of massive strikes took place in 1890 and 1891.

Throughout the boom times of the 1880s, unionists had been fighting to organise workers across the country, aided by newly formed trades and labour councils that were playing an increasingly important role in dispute arbitration.

Unionised worker numbers peaked in 1890 with 200,000 members spread across 1400 unions, making Australia the most unionised nation in the world per capita. With workers better organised, industrial actions also increased during the decade with the unions winning significant victories.

This forced employers to become more organised, and the formation of the Victoria Employers Union heralded a new, more coordinated and hardline approach from employers towards their workers’ demands.

In March 1890 labour delegates from the colonies’ major ports met in Sydney for an all-Australia wharf labourers’ federation meeting. Within this group, ships’ officers formed the Mercantile Marine Officers Association and the Melbourne branch affiliated with the Melbourne Trades Hall.

Ship-owners immediately condemned the officers’ organisation and tried to stop it from recruiting members. Negotiations broke down between ship-owners and unions on 15 August 1890 and the next day marine officers left their posts.

Unions also associated with the Trades Hall affiliation began to strike in support of the maritime workers. Coalmining unions refused to supply coal for ships; gas stokers went out on strike; in September, transport unionists walked out; and days later, shearers’ unions imposed a ban on processing non-union wool.

By the end of the month 50,000 workers across Australia and New Zealand were on strike.

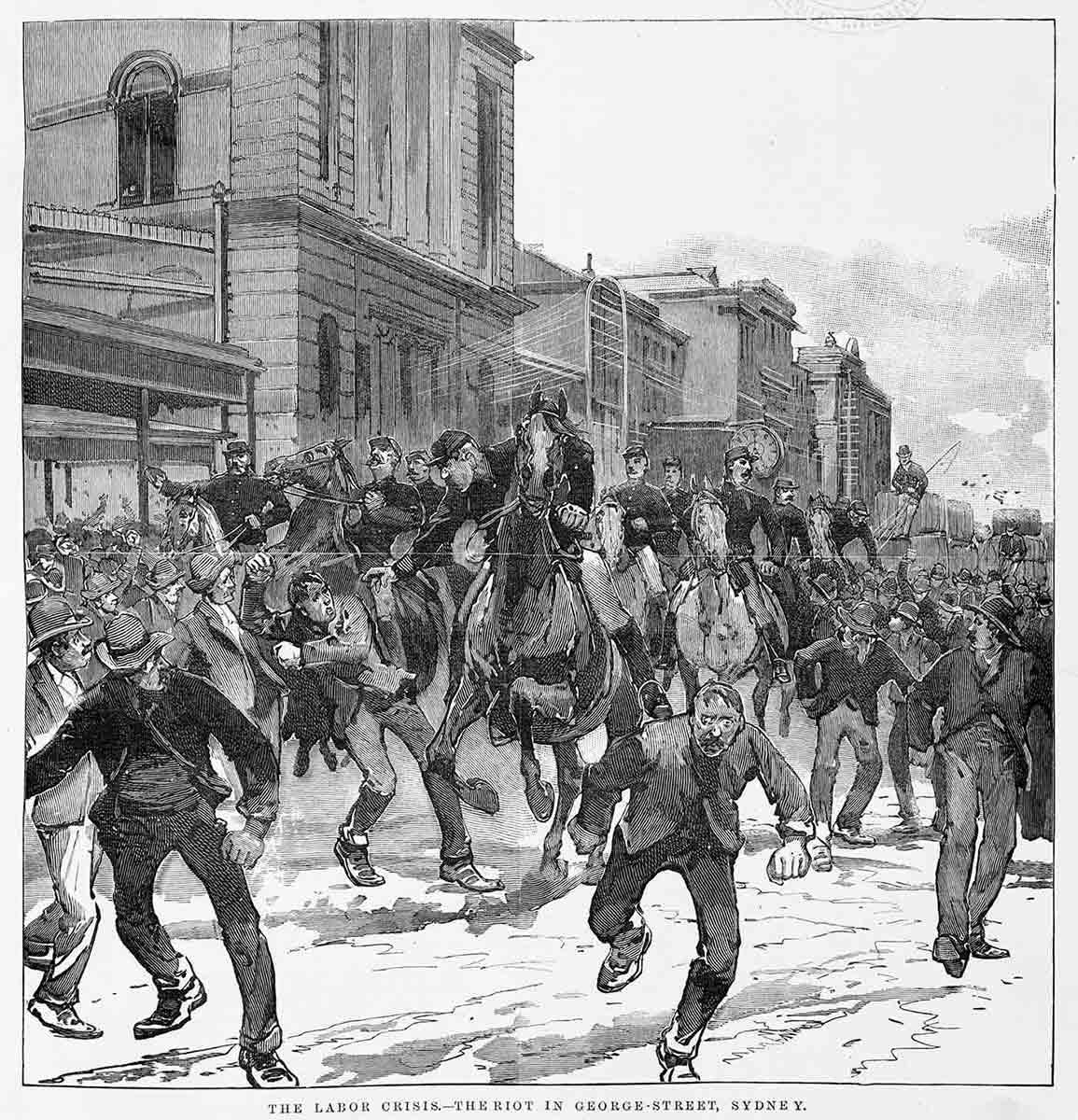

Under pressure from a contracting market and unionised labour pressing for more benefits for their members, the employers took a stand. With the recent downturn in the economy there were many unemployed men and the employers hired them to replace the strikers, using police and military personnel to get these workers through union picket lines.

Violent disputes erupted around the country and the strike dragged on but the employers had enough money, scab labour and political support to outlast the unions and in November the marine officers returned to work on the employers’ terms.

1891 shearers’ strike

The maritime strike had failed and the animosity felt by the unionists continued to simmer. At the 1890 annual conference of the Australian Shearers’ Union in Bourke a new rule was brought into effect whereby unionists were prohibited from working with non-union labour.

Soon after, union members at Jondaryan Station on the Darling Downs in Queensland went on strike over being made to work with non-union labour. They won the dispute with the help of wharfies in Rockhampton who refused to handle non-union wool.

In reaction, station-owners at the Inter-Colonial Conference of Pastoralists later that year decided to cut shearers’ wages and give themselves the option of hiring non-union labour.

In January 1891 the manager of Logan Downs Station asked shearers to sign a contract that incorporated the new agreement. The workers refused and called a strike until a list of demands were met including: continuation of existing rates, protection of workers’ rights and privileges, just and equitable work agreements, and exclusion of low-cost Chinese labour.

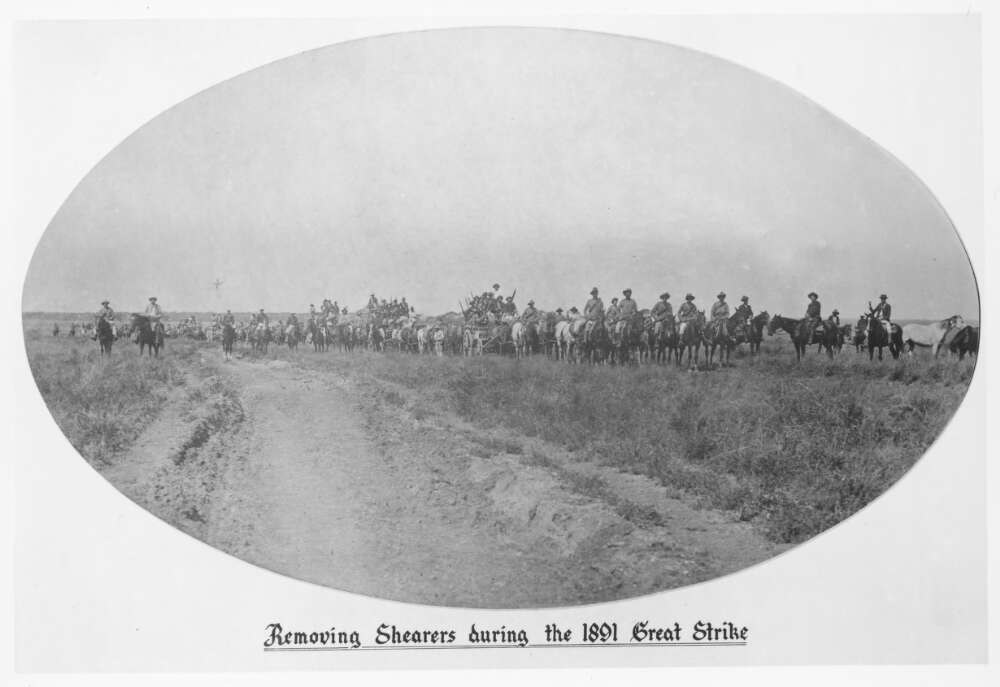

The strike spread quickly with organisers forming armed strike camps outside towns across central Queensland. More than 2000 soldiers and police were brought into the area and 1099 special constables were sworn in to protect non-union labour and arrest the strike leaders.

The strikers retaliated by harassing scab workers and raiding shearing sheds. On 21 February, the Brisbane Courier announced: ‘Yet true it is that on our great Western plains the opposing forces of civilisation and revolution are gathering and … conflict is inevitable’.

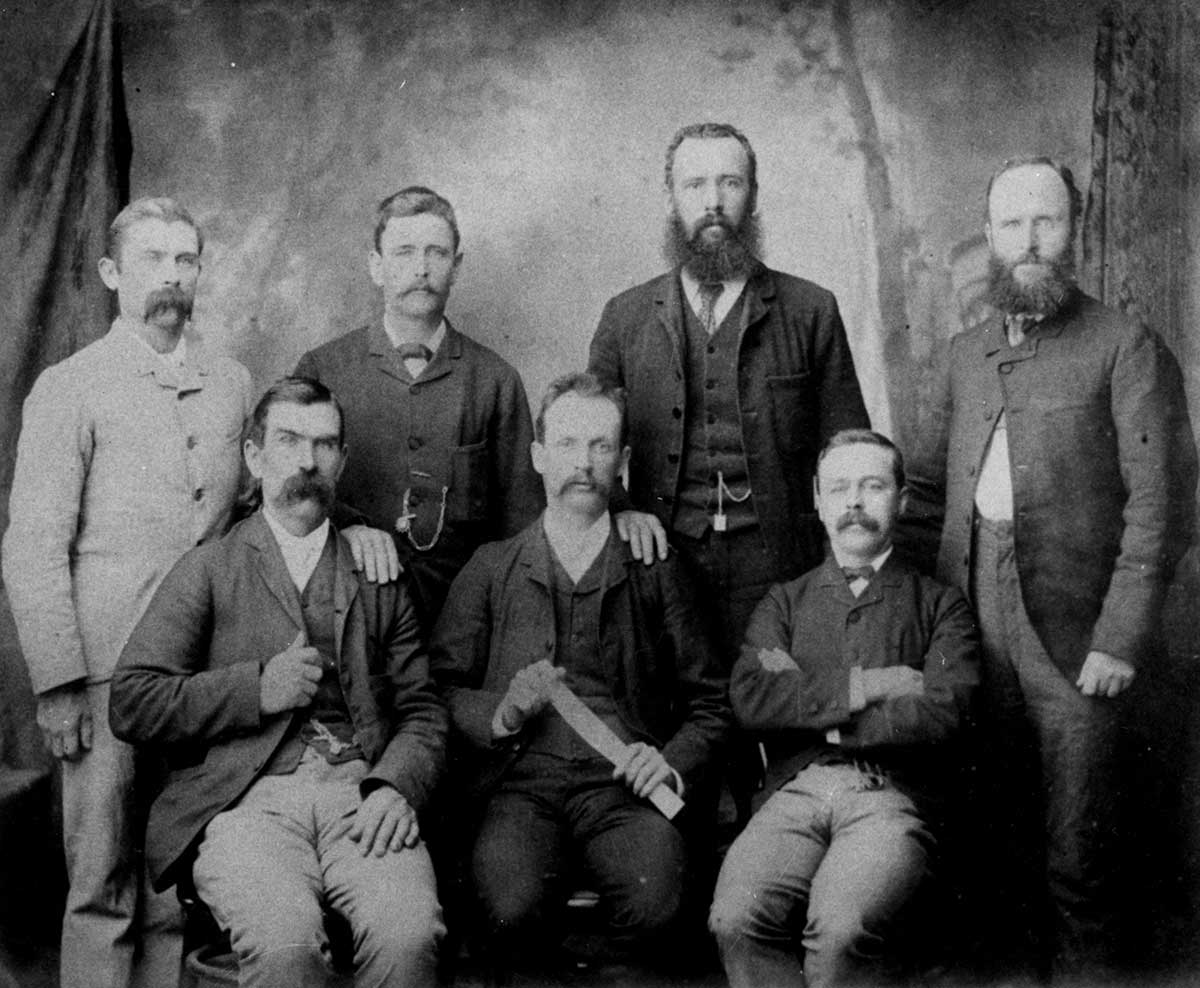

In a carefully planned operation on 28 March, police arrested a group of the main organisers in Barcaldine. By April, there were 8500 strikers across 22 strike camps, but though there was sporadic violence on both sides, it remained isolated.

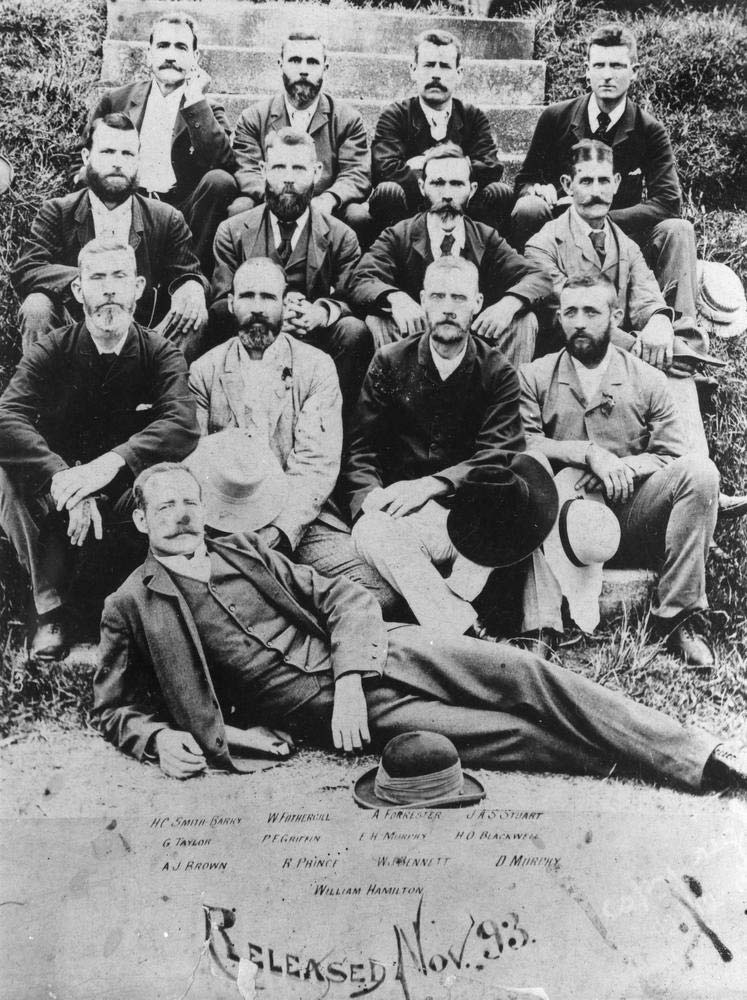

The arrested strike leaders were subjected to a highly politicised trial and on 20 May were sentenced to three years imprisonment on St Helena Island off the Queensland coast.

By 11 June the shearers were unable to hold out any longer. The strike camps were full of hungry, penniless shearers and with the depression in full swing there was little chance of them finding work.

Formation of the Australian Labor Party

The brutal suppression and lack of results from the maritime and shearers’ strikes brought activists to realise that industrial action alone would not bring about progress for the working class and that a political party representing the rights of working people was needed.

Labor leagues were created across Queensland, South Australia and New South Wales over the next year and each contested their respective upcoming colonial elections.

In 1891, the Labor Electoral League of New South Wales won 35 of 141 seats and held the balance of power. In the same year three United Labor Party of South Australia members were elected to their colonial legislature.

Then in 1899, with the resignation of the incumbent conservative government, the Queensland Labor Party under Anderson Dawson formed the first Labor government in the world.

The state Labor parties were generally opposed to Federation, with some claiming that the proposed senate, modelled along the lines of the British House of Lords, was too powerful and non-representative and that federating the colonies would further embed conservative power.

Federation went ahead despite Labor’s misgivings and by 1899 the state parties conceded they would need a coordinated policy platform from which to attract the Australian voter. In January 1900, 27 Labor delegates from New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia met in Sydney to agree on a common approach.

In the first federal election in March 1901, state-based Labor candidates won 24 of 111 seats and secured the balance of power between Protectionists and Free Traders in the lower house.

On 8 May that year, the first meeting of the federal parliamentary Labor Party took place.

Then in April 1904, Prime Minister Alfred Deakin fell out with Labor leader Chris Watson over industrial relations issues and Deakin resigned. Free Trade leader George Reid declined to take office, leaving Watson to form a government, the first national Labor government in the world.

Labor legacy

The Labor Party continues to be a major political force in Australia and is one of the two major parties at both the federal and state and territory levels.

Early Laborites believed their party’s mission was to create a more equitable society than could be achieved through reliance on the free market alone.

There is no doubt that it allowed members of society that up until the 1890s had no say in government to participate more actively in the political system.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

You may also like

References

Chifley Research Centre, Labor History

Nick Dyrenfurth and Frank Bongiorno, A Little History of the Labor Party, UNSW Press, Kensington, NSW, 2011

John Faulkner and Stuart Macintyre, True Believers: The Story of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, Allen and Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2001

Ross McMullin, The Light on the Hill: Australian Labor Party, 1891–1991, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1991