On 10 June 1908 the newly formed Commonwealth Parliament passed the Invalid and Old-Age Pensions Act. The legislation was groundbreaking.

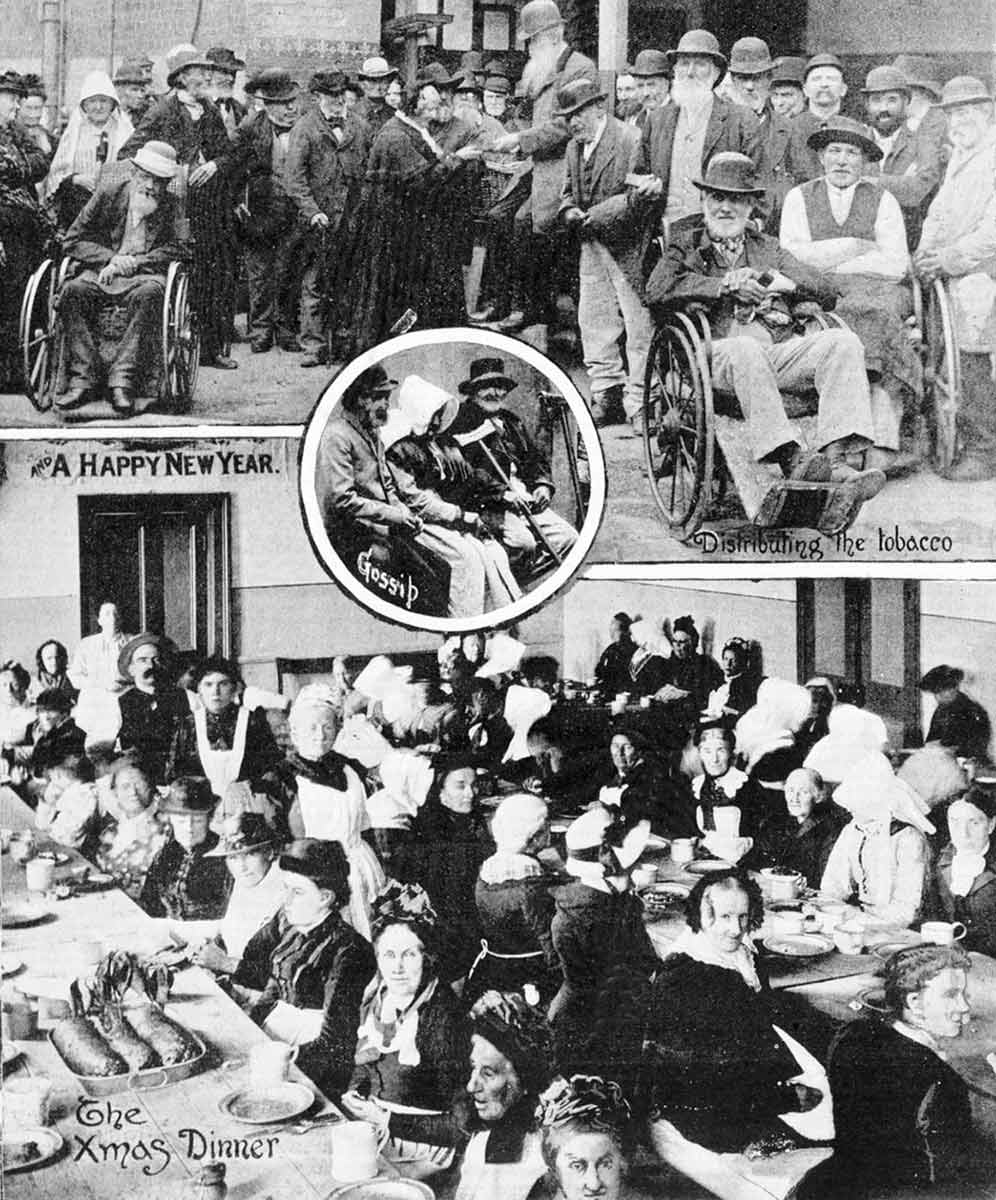

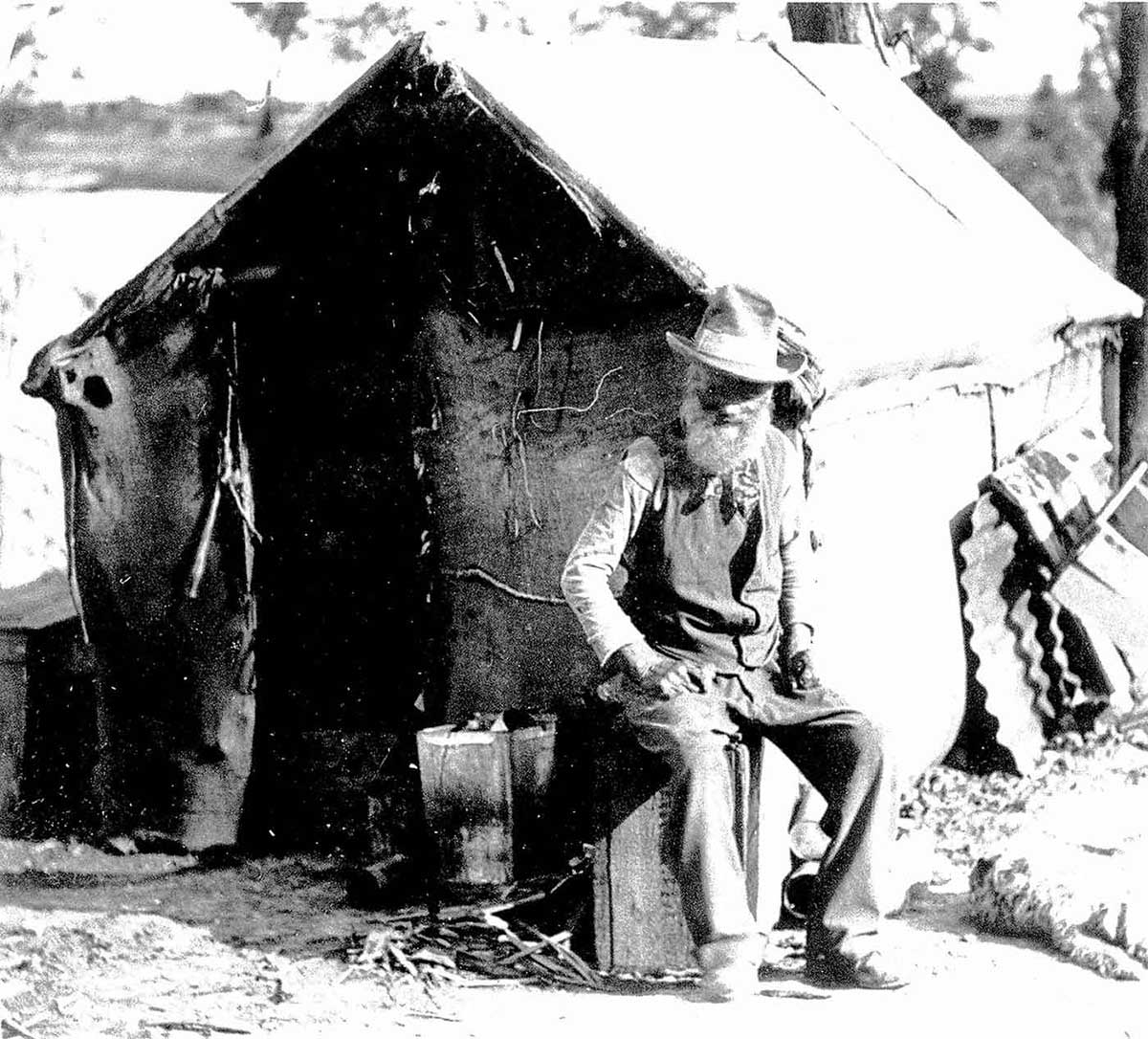

Prior to that, the elderly or infirm received no financial support and their care fell either to family, religious and charitable institutions, or government asylums. Life in such institutions was often far from easy.

Following the economic depression of the early 1890s, when poverty became widespread, who should support those unable to look after themselves became a hot issue.

Warwick Examiner and Times, 5 October 1908:

The scene at the Police Station on Saturday was pathetic in many respects. The old bowed forms and grey heads, the slow hobble with the aid of sticks, were all reminders that fortune looks coldly on some while smiling on others, and that in life's battle some are sorely buffeted. It is, however, gratifying to know that those who have grown old, and often helpless, in the industrial service of their country, will be able to pass their declining days in a fair amount of comfort.

Debating the pension

Australia had a history of innovation when it came to social and political rights, which affected how people thought about the provision of pensions.

These innovations included the introduction of compulsory primary schooling, the emergence of a strong labour movement that helped to gain shorter working hours, and the extension of universal voting rights. (See 'Related Defining Moments' below).

The quality and availability of accommodation for the elderly and infirm varied widely across the colonies. In some areas, a shortage of both mental asylums and asylums for the destitute meant that the homeless found themselves sheltered in lunatic asylums, and the mentally ill were housed in institutions for the destitute.1

Proponents of introducing a pension argued that a person had a right to live out their old age free from poverty because of their contribution to the community through a lifetime’s hard work. They also argued that the pension had to be free from the stigma of charity, and that a universal government scheme funded from general revenue was the best policy.

Several colonies debated the possibility of providing an old age pension, either by establishing Royal Commissions or commissions of inquiry through their legislatures. This was in line with international developments – New Zealand, Denmark and Britain were all engaged in similar policy debates.

The national importance of the subject was shown by the fact that the Constitution included provisions for monetary allowances. During debates at the Melbourne Constitutional Convention, no delegates disagreed with the idea of pensions, but they did disagree over whether it was best for the states or the Commonwealth to administer it.

However, section 51 of the Constitution gives parliament the power to legislate for:

- (xxiii) invalid and old-age pensions;

- (xxiiiA) the provision of maternity allowances, widows’ pensions, child endowment, unemployment, pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, medical and dental services (but not so as to authorize any form of civil conscription), benefits to students and family allowances.

Pensions at the state level

New South Wales introduced legislation in 1900. Every person in the community (unless ‘aboriginal, alien or Asiatic’) who was above the age of 60 years, who had resided in New South Wales for 15 years and whose income did not exceed £50 a year would be entitled to a pension of ten shillings a week when single.

Married couples received 15 shillings a week, which was more or less adequate. Similar legislation was enacted in Victoria (1900) and Queensland (1908). New South Wales introduced an invalid pension scheme in 1908.

The federal government therefore had a rich legacy of experience to draw on in setting out a national scheme.

A royal commission concluded in 1906, which recommended a scheme largely based on the New South Wales legislation. It recommended that men over 65, and later, women over 60 be eligible. Their income had to be less than £52 a year and assets, such as a home, could be no more than £310 in value. Residence of at least 25 years was also a requirement.

The pensioner also had to be of ‘good character’, which generally remained undefined, although those who had deserted their spouse and children in the previous five years were not eligible.

National pension scheme

In 1908, the Australian Parliament passed the Invalid and Old-Age Pensions Act, which incorporated the royal commission’s recommendations. The reason for the delay was a debate over how to fund the scheme. Negotiations led to legislation that would allow the federal government to withhold some of the money it distributed to the states from customs and excise.

It is important to remember the great difference in life expectancy between then and now. At Federation, only four per cent of the population were over the age of 65.2 Men could expect to live 55 years, and women for 59 years.

The financial cost of such a scheme was very small in comparison to today, when 15.9 per cent of the population is over 65 and both sexes can expect to live into their eighties.

Notes

1 ‘“Poor Naked Wretches”: A Historical Overview of Australian Homelessness’ by Clem Lloyd in A History of European Housing in Australia, Patrick Troy (ed), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000, p. 292.

2Australian Historical Population Statistics, 2014 – Australian Bureau of Statistics

Explore Defining Moments

References

History of pension and other benefits, Australian Bureau of Statistics

History of pensions in the UK, Pensions Archive

Invalid and Old-Age Pensions Act 1908, Australian Government’s ComLaw

TH Kewley, Social Security in Australia: The Development of Social Security and Health Benefits from 1900 to the Present, Sydney University Press, Sydney and Methuen, London, 1965.

Pat Thane, Old Age in English History: Past Experiences, Present Issues, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000.