Chaired by Professor John Maynard with panellists Esther Carroll, Ollie Campbell, Dianne O'Brien, Barbara McDonogh and Barbara Nicholson, National Museum of Australia, 9 July 2008

MICHAEL PICKERING: I would first like to acknowledge the Ngambri and Ngunnawal peoples as the traditional owners of the Canberra region. They are consistent contributors to the National Museum of Australia’s cultural life, and we are very grateful for their continued assistance.

This forum has been organised to celebrate the Indigenous activists of the 1920s and 1930s. It is a particularly suitable year, being the seventieth anniversary of the 1938 Day of Mourning which initiated in Sydney. The people we are celebrating here are those well-known figures from the time - Fred Maynard, William Cooper and Jack Patten - and less well-known activists such as Jack Tattersall who was part of the Day of Mourning group and who also worked for the improvement of conditions on Coomaditchie mission, Port Kembla where he lived.

For this celebration we are privileged to have with us here today some people who have had a very personal connection with that time in history. In particular we welcome Aunty Esther Carroll and Aunty Ollie Campbell. Aunty Esther and Aunty Ollie were actually there at the event on the Day of Mourning. We have their photographs on the wall over there as well. Professor John Maynard is the grandson of Fred Maynard. Dianne O’Brien and her sister Barbara McDonogh are the descendants of William Cooper. Suzanne Ingram’s family was also very closely involved with the Day of Mourning organisation. And Barbara Nicholson is the daughter of Jack Tattersall. I will be leaving them to tell their own stories and their own experiences and also the stories of their own lives.

As well as our distinguished visitors and guests, you will notice these objects we have from the museum collection. We have a boomerang which belonged to Jack Tattersall and which his daughter Barbara has generously donated to the Museum. We also have a protest banner of the Australian Aborigines League which has survived from the times. Most banners don’t survive the event - this one did. It becomes an icon for what happened then and for what has followed subsequently. The banner was produced by Bill Onus, another participant in the Day of Mourning and a lifelong fighter for Indigenous rights. The banner was presented to the Museum by Gary Foley, another well-known Indigenous fighter and activist. And lastly we have the painting by Bill Onus’s son. This is also from our Museum collections and certainly tells a powerful story and puts activists into a familiar context: the role of the police in the removal of people from homes at the time lingers in history.

The significance of this event is that Australia is emerging from what I think is a small ice age which has lasted 11 or 12 years in which attempts were made to hide history. What has happened is that the stories have not been suffocated. We have learnt through this time that history affects lives of people today. It’s not frozen in time. Everyone’s lives have been affected by the events of the Day of Mourning, the protest movement, civil rights and the 1967 Referendum. These activities in history have shaped our lives will shape our lives, and will shape the lives of our children. In particular, they have shaped the lives of the people who are here today. We thank them for their willingness to be here and to share their stories with us. I will now hand over to Professor John Maynard.

JOHN MAYNARD: Thanks very much for that kind introduction. As a Waremei man from the Port Stephens area just north of Newcastle, I would also like to pay my respects to the traditional custodians, the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, and their ancestral lands within which we are most honoured to be a visitor and I would also pay respects to our elders past and present.

As an individual, and I am sure I can speak for the other people on the panel, I am most honoured to be here and take part in this forum which I see as a most significant event. I really pay my respects to the National Museum for organising it, and in particular to Jay Arthur and Troy Pickwick for the invitation to come down to this most significant event to honour the memory of some very legendary Aboriginal pioneer activists who were brave and courageous at a completely different time from what we have now, although it is certainly the position that Aboriginal people find themselves in today. We still have a great fight and a struggle that goes on. The comment that we have come out of a bit of an ice age - I have been brushing the ice off for the last 11 and a half to 12 years. It has been a pretty frozen time as far as Indigenous history is concerned. There is no doubt there was a process of taking Australian history basically back to the 1950s and glorifying the history of that time period - glorifying the history of the settlers, the discoverers and the pioneers, and an Aboriginal place in that history was pushed on to the back agenda.

Today we are so fortunate to have such a number of the descendants of people like William Cooper, Bill Ferguson, Jack Tattersall and me with my grandfather Fred Maynard. It is not just going to be us talking about our ancestors in the sense of what they fought for - although I am sure that will be a part of it because we are very passionate about that and I am sure we will be able to express that - but it is also importantly about what that means to us as individuals, what it has meant with regard to our families, what it has meant to us as regards to our communities, and certainly what it has meant to us in the sense of a Aboriginal nation as whole. Because it is the inspiration of these people and what they stood for and what they still stand for which is the force that we carry. Certainly what I have done, whether it is in academia or how I conduct myself in public or in private, has a lot to do with the memory of my grandfather and what he stood for and the respect that his name actually carries. I am sure I speak on behalf of the other descendants in that regard.

Our first discussion is in regards to Bill Ferguson who is going to be talked about by Aunty June Barker. There is a connection that we are to link up with. Is Aunty June on the line somewhere?

JUNE BARKER: Yes.

JOHN MAYNARD: There she is. How are you, aunt?

JUNE BARKER: Yeah, I’m really good.

JOHN MAYNARD: It’s great to have you with us.

JUNE BARKER: Thank you.

JOHN MAYNARD: As you would have heard, I am sure you are going to give us insights into your grandfather Bill Ferguson, your memories of him and certainly the importance and role that he played in early Aboriginal political activism but also how it impacted on to you and your family and the community and, as I said, the wider community. Would you like to open up the discussion in the memories of Bill Ferguson?

JUNE BARKER: First, I would like to say how brave they must have been back in those days to speak up and stand out against the white Australians. Sitting here now today and listening to the words that have been said down there, it takes you back. I get the feeling in my heart and in my chest that that’s how they must have felt on that day when Australia celebrated the 150th anniversary and our people in the Australian hall had nothing to celebrate and they called it a day of mourning. I have looked at the photo of the children standing in front there, and throughout my life I knew what it was all about.

I knew why my grandfather went down to the Board [New South Wales Aborigines Protection Board] meetings, down to Bridge Street. I now know why there always used to be Aborigines coming to where they lived in Dubbo at No. 1, Wingiwarra Street. He would be sitting there writing letters. I know now they must have been letters of complaint that he was taking down to put before the Board. The soldiers that were stationed there in Dubbo, they came from all over Australia and they would spend some time there with my grandfather. When he would go to the Board meetings, we’d run across to the railway station to wave to him, because we knew that he was going down to the Board meetings. All throughout my childhood that was all I knew about. Even though I lived on the Brewarrina mission with my parents I knew what was taking place.

In 1938 I would have been only very small but Roy, my husband, has a good memory and he remembers the day when Bill Ferguson came to the mission to hold meetings with the Brewarrina mission people and the manager hunted them off the mission station. They all walked off, women, children and the men, to get off the government Aborigines protection land, to get out through the gates and they held the meeting there. The kids gathered lots of wood and they made a big fire and everyone sat around while he had the meeting there.

Many years after that I was a girl of I guess about 12 or 13 in Dubbo. If you know Dubbo, the swimming pool is not far from the railway station, and there used to be - they called it the Railway Institute Hall. With a cousin of mine we were walking past and we seen all the Aborigines there in Dubbo. They are called Murris. I could see straight into the hall, and this picture has stayed with me all throughout my life. We heard the loud voice, and I knew it was my grandfather’s voice. We stood and looked and we could see straight into the hall. I can still see him standing there out the front inside the hall and speaking. His voice came out of that hall loud and clear, with no microphones or anything back in those days. I know that he did have a loud, clear voice. That is one memory of my grandfather that I have carried all through my life.

Also living in Brewarrina there at the mission, my childhood was all about the struggles, how the mission manager would be saying, ‘They’re woeful people. We’ve got to get rid of them.’ They’ve got no sympathy towards our Aboriginal people. Later on in my life I understood all that. I just knew how humiliating, how degrading, how all these feelings were to be living on a mission with a manager over you. Men that weren’t very nice people. People that wouldn’t let our Aboriginal old people speak their language - they called it mumbo jumbo. A man that would humiliate those old full-blood people. They spoke so many different languages there on Brewarrina mission. The Wongamara they brought from out Tibooburra way and the Angledool people - these people were all forcibly removed to the Brewarrina mission. So I grew up hearing all sorts of different languages spoken there, but being stopped by the white man of the mission. Sad to say today I can’t speak the language. It’s gone. We know everyday words that we picked up so at least we still remember.

It’s good to have a good memory to think back to those days. I was born on Cumeragunja mission in 1935. My mother was of the Yorta Yorta people and my father Duncan Ferguson was from the Wiradjiri people, born over there at Darlington Point, Narrandera. All throughout my life I have known all about the struggle that they had. I know that there was others with my grandfather, like Jackie Patten, William Cooper, Doug Nicholls, Mr Charles Leon, Billy Reid. Billy Reid was another very strong person back in those days and Jimmy Barker on the Brewarrina mission used to write letters to Bill Ferguson, the same as his own brother down on the Menindee mission. They would send these letters I believe to my grandfather putting in little reports here and there of the treatment that their people were suffering on the missions.

It’s good that I can still remember. I think it is good. I can still see different things in my mind’s eye go right back to the hardships on the missions and know just what our people suffered and what these brave men were speaking for. If they wouldn’t have spoke out back then, where would we have been today? I often wonder.

We go down to Yetta Dhinnakkal to the corrective services there, and it is sad to see our Aboriginal young fellas there, all first offenders. They know nothing of their Aboriginal history. Roy and I go there as mentors and talk to them about such things. They like to know all these things that have happened to us. We say what happened to us out here happened to your people too. Wherever you came from - north coast, south coast, wherever - all our people suffered the same way through these managers on the missions. Our people were humiliated by the police too at Brewarrina there. We would have to run and hide when we seen the side car coming to the mission it was such a frightening thing - always living in fear. It’s a terrible thing to live in fear. I know what it’s like, and others that lived on the mission there with us kids at that time.

My grandfather and my aunties and uncles living in Dubbo didn’t know much about the happenings on the missions like my family and I did, because we lived through that. There is none of them - like my father or his brothers or sisters - none of them followed my grandfather into politics. But my father Duncan Ferguson accepted the Christian religion and the Christian life. He never regretted it, and we always had a good relationship throughout the years. In Brewarrina he just lived at Weilmoringle and Dinnawan Gadooga just caring for our Aboriginal people out there on the spiritual side of our lives.

Perhaps if I would have had an opportunity which never came my way with education back when I was younger, maybe I would have been able to speak up better and speak for our people. Like back in 1974 there was a health worker’s job advertised in Brewarrina and I applied and I got that position. I still had that good feeling of helping our people when you would see some old fellow from Weilmoringle sitting there early outside the doctors when the big specialists would come. Bringing more people back, driving them up, and I said, ‘Hey, uncle, what are you doing here? You’ve been here early.’ ‘Oh yes, I’ve got to see the doctor.’ I said, ‘Come on in with me now.’ So I took him in and I said, ‘Look, old Mr Bailey has been sitting out there since 9 o’clock, and no-one has seen that he came in.’ ‘Oh, come in, Mr Bailey.’ They turned and switched their story, but things like that.

Over the years, working there for about eight years in Brewarrina, I have seen the way our people were still treated, still put down, still neglected people. I am glad that I was able to assist them, to help them with a good feeling in your heart towards your people. I know that back then in January 1938 they had that feeling too. They wanted to help our people, their people.

Another thing, too, that I was told about the Day of Mourning. After that meeting that day - I don’t know if anyone else knows of this - I was told by an old woman out there at La Perouse who said to me back in the 1950s when I went out there, ‘Oh yes, see down there, when they held that big meeting we went down there to the beach and we put all the pretty flowers in the water and we watched them float away.’ So I have always had that memory, and that old lady, I think they called her Lily Foster. She used to run the hostel out there at La Perouse, Aunty Lily Foster. She took us kids down there to the beach and said, ‘Oh yeah, this is the place here where we threw all the flowers in in memory of the Day of Mourning.’

JOHN MAYNARD: That’s such a powerful story, and I think you have given a great insight into the story and power of the message that your grandfather told. I think you sell yourself short. I think you and Uncle Roy have played a significant part in the decades since in the role you have played not just in your local community but the inspiration you have given to many others. I can speak for many people in respect of that, because you have been inspirational in your own ways without a question, so I think you are following on the tradition of your grandfather Bill Ferguson in that sense. That is without question.

It’s a great story. It’s not just about 1938, because that was much more than that with the repercussions that came afterwards and that continue. What you said too about going into the jail system and visiting young Aboriginal kids and the people that have been sentenced and the role that you and Uncle Roy play with the importance you have placed on these people actually gaining their history because Aboriginal history in this country is like a giant jigsaw puzzle. Most of the pieces are missing, and we are still in the process of putting those pieces back. Just you relating the stories here today has played a significant part of that and we certainly thank you.

JUNE BARKER: Can I say one more thing before I go?

JOHN MAYNARD: Yes, sure, aunt.

JUNE BARKER: Going into schools and even down at the jail, you see all skin colours now, you know what I mean - blue eyes looking at you, lighter skins, darker skins - and we always say to them, ‘It doesn’t matter what our skin colour is, our eye colour, our hair colour, we still descend from the first people of this land.’ Thank you.

JOHN MAYNARD: That’s right. Thanks very much, aunt. (Applause)

Moving on now to the descendants of William Cooper and Jack Tattersall, we have Aunties Dianne O’Brien, Barbara McDonogh, and Barbara Nicholson. Again a similar thing if you would like to give us your thoughts and comments of these impressive people and the role they played in the past but also how it has impacted on you as individuals as you have moved through your life in your particular journey and what it has meant as far as inspiration is concerned.

DIANNE O’BRIEN: Well to me, I found out my inheritance when the kids went to school and when they used to have a thing called Abstudy that used to be $3 a fortnight or something. A guy called Donny Williams come along and he said, ‘Your kids should be getting this Aboriginal money,’ and I said, ‘Oh no, we’re not Aboriginal, we are some kind of wogs or Heinz variety, I don’t know, but we’re not Aboriginal.’ Anyhow it took Donny about a month. He got on to the Aboriginal Link-Up and through Peter Read and Coral Edwards, they both come up to our place and they done a search.

Now I had been looking for my people for about five years and come to a dead end all the time. Within 12 months Peter come back and said, ‘You’re a link that is missing in William Cooper’s family tree.’ Then they said about my great-grandfather being this great activist. He is a great man. So I wanted to go back Cumera, so I went out to Cumeragunja - Oh, that was an eye opener - and learnt a lot about my cousins and ancestors.

Before this I was a pretty wild person with six kids on my own. I was right into land rights and the Aboriginal Legal Service and done a lot of protesting. So when I went to Cumera I saw how run down the place was, so I started to become the housing commission - it’s called CHADIC, Cumeragunja Housing and Development - and put in submissions for houses, sewerage, water, roadways, and everything looked great. So I start to grow up a bit like I was still pretty wild. I saw what was happening so we did this community development stuff, and everything was great.

But in the meantime people said I didn’t belong to William Cooper and that I belonged to the white William Cooper that lives in Penrith and that Link-Up was wrong. So we had to do some more research. My kids followed me down there. That was a good goal for my kids to learn the life living on a mission. At one stage there it was that bad they said, ‘Mum, we’re glad you were taken away, because if we had to grow up here we wouldn’t survive.’ I was a bit upset about that.

The kids went back to Sydney, and I stayed behind. I stayed there for eight and a half years but only through Aboriginal Link-Up finding that link that I found my link. I had always done this stuff like marched and that. I was doing it for my people, but whose people? I didn’t know whether they were Yorta Yorta, Bangarang or Wiradjuri. So it was that connection to my great grandfather that I belonged.

Apparently some quotes that I made at some land council speeches, the quote that I used to do all the time which I have forgot was in my great-grandfather’s book. It just felt like the spirit is there and is following me through. When I talked about land, health and education it was like him talking. My great-aunties used to say that it’s your great-grandfather talking.

Anyhow I moved up to the Central Coast and I work in the Aboriginal community but I work for Gosford area health hospital for Northern Sydney Central Coast Area Health and I work there in sexual health promotion but I do education programs in the community with our people and also with the needle exchange program. I won an Australia Day award in 2006 for the best services in our community. I also sit on the board at the Aboriginal Medical Centre at Wyong. I’m the chairperson of Mindaletta Aboriginal Corporation in Umina. I’m the board member of the Aboriginal Land Council in Wyong and I sit on the Aboriginal Health Workers Forum in Sydney. And I work full time.

I have 28 grandchildren and 21 great grandchildren. It’s a full-time job trying to make the young ones get back to reality, get back to the old way and get that respect back that we used to tell the kids when we were kids - it’s gone and we’ve got to get it back. You know, ‘United we stand, divided we fall.’ That about finishes my life as William Cooper’s granddaughter. My mother is still alive. She is 89 and lives in Granville. She is a very private person whereas I am the opposite. I am just out there. She gets a bit upset sometimes about that, but anyway life goes on. Thank you very much. (Applause)

JOHN MAYNARD: We will keep moving down the line - Barbara one.

BARBARA McDONOGH: I have never done anything as elaborate as Dianne; I wish I had. I was about 14 when I found out that I had darker relatives but I didn’t know where they come in. I asked a lot of questions but didn’t get many answers. One aunty gave me some answers, but not many.

It wasn’t until I was 34 that I found out I was related to William Cooper. I only found out because my mother said I was related to him because we wanted a housing loan and she told me to apply for it. And I got a letter from Molly Dwyer from the Victorian Legal Service. She sent a letter. And that’s when I found out that I was actually William Cooper’s great granddaughter. I am sorry I didn’t do any of those things. I would have liked to have but I have not had the education. But my daughter, she is following, she is going to do it. I have two sons that are going to do it. Two children that aren’t interested in it and that don’t want to know. That’s about it because I would like to do a lot more but I’m getting towards the end of my Dreamtime.

My daughter and my grandsons are absolutely wrapped in the idea. They’re interested in it. For them to find out, we go back seven generations. How many people, even white people, how far can they go back? Not always. We’re lucky that on the Aboriginal side we can go back seven. I think that’s absolutely marvellous, and we know where we come from. I think the children need to know. That’s the whole point. They’re not interested. They’ve got to be taught. They have to find out now that that’s your heritage and learn to live with that heritage, because it is all getting mixed up and it’s being lost.

JOHN MAYNARD: That is crucial. That is what Aunty June touched on, the importance of our history particularly to the generations to come. We have such incredible heroes and heroines in our past and the greater knowledge of that which has impacted on to them. Like when I started school in 1959 and left in 1969, I didn’t have any fond memories of school at all. There was nothing about Aboriginal history or culture in the school curriculum. I wasn’t encouraged. I got the cane most of the time. I was ripped up out of the seat by the hair and spent most of my time looking out the window. The only blackfella I read about in that particular time period was Jackie Jackie and he was a ‘good’ blackfella. The time is different. For our future generations to know they have this incredible history not just in the traditional past but across the last 200 years many brave people, Aboriginal men and women, who stood up and were counted for and spoke out about what our people faced right across the country. These are inspirational people, very brave courageous people.

BARBARA NICHOLSON: I would like to talk a little bit about that 1938 day and my father’s role in that because it was just such a significant time in history. I agree with what has already been said that those people were so brave, because in those days it was a criminal offence for Aboriginal people to publicly congregate. So they could have all been arrested and thrown in jail. But they had a lot of support - they had support from the black quarter and they had support from the white quarter at well vis a vis the Waterside Workers Federation and I know the Communist Party also helped them.

My father was a waterside worker in Port Kembla. I didn’t know him. I got all this history later on. I was never allowed to know my father. My father was also on the Illawarra Aboriginal Advancement League, which I think was a spin-off thing from VAAL, the Victorian Aboriginal Advancement League. In that capacity, as I much later found out - because I didn’t experience his history first hand; I had to learn it - he worked tirelessly for social justice for Aboriginal people. He wrote and took up petitions to get housing for Aboriginal people, the copies of which are in state archives. He tried to get land for Aboriginal people. He tried to stop the taking away of Aboriginal children. He was hot on education for Aboriginal people. And he marched in 1938, along with all those other nameless faces in that 1938 march. One of the reasons I agreed to be here today was to put that right, to get his name up there, maybe as a representative of all of those other nameless faces, one that I know that could and should be immortalised along with all those other more well-known people. I hope I can achieve that. I hope this forum achieves that.

I know he was an activist. I know he struggled hard for all of those things but I didn’t find that out until much later. I didn’t get to know him at all. I didn’t even know his name. And when I finally did get to do the searches through Link-Up he had already passed away. When I located his grave I found black politics on that very day, because I experienced all that pain of my father not knowing his one and only child, me, not knowing his grandchildren and us not knowing him. I had always been pretty much of a political animal but that was the day. I stood at the crematorium. They had been doing some renovations and the brick wasn’t in the wall. The wall had been taken down, but the people at the crematorium actually brought me the plaque with his name on it and I held it in my hands. I looked at that, and that was the day I wanted to get an AK47 and go and blow up parliament. That was the day I found black politics and I have been active in black politics ever since.

I think I have marched in just about every protest march that you can name. I committed myself to the Link-Up organisation. I am still on the executive board of directors of the Link-Up organisation and will remain so until the day I do or they kick me out, and I don’t think they are likely to do that. I am one of the longest serving members on Link-Up now and I have the institutional memory so they can’t get rid of me, I hope.

I was one of the founding members of the Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Watch Committee and I served eight years as chairperson of that committee. In that capacity I had lots of contact with Aboriginal inmates and families of the victims of deaths in custody. I did the hard yards all that way and in the whole process I went and got myself a tertiary education. I finished up teaching in universities and I am still connected to the University of Wollongong. I do lots and lots of stuff like that.

I am also a member of the Indigenous Social Justice Association and I have served on the AMS [Aboriginal Medical Service] board of directors. I have had a couple of stints on that. Generally I have done all that and raised a big family. I have 16.2 months grandchildren, seven months to go before it arrives, and one great grandy.

If I go back now to the 1938 stuff and my father’s role in that, I think there is a real synergy with what happened later in my life. Before I actually found out that my father had been involved in the 1938 stuff I got drawn in with the Aboriginal History and Heritage Council in Sydney via my old aunt, Aunty Nelda Rome, Jenny Monroe, who was then chair of the Metropolitan Land Council in Sydney, another Aboriginal women from Sydney, Doreen Kelly, and a French woman by the name of Gisele Maceqa, who was a student at UTS in Sydney. Aunty Nelda Rome had got Gisele to do her research paper on the 1938 Day of Mourning. And out of that research Gisele uncovered the fact that there was a development application on the old Australia Hall, the site of the meeting in 1938, so Gisele embarked on a mission to stop that. So she called in Jenny, Doreen, Tony [?] McEvoy and a few others, we all got together and we formed the Aboriginal History and Heritage Council to go to war on saving the Day of Mourning site.

We fought a six-year battle to get that site. We took up petitions and did all sorts of things over the six-year period. On the 60th anniversary we had a re-enactment march in Sydney where we gathered at the Town Hall. If my memory serves me correctly, our good friend Jack Horner was also present on that day with a lot of descendants and I think a couple of the originals. We have got it at last. Jack and I have been trying to work out where we first met. We marched from the Town Hall following the same route as the original protesters did in a silent march, remembering that the original protesters were doing that at their peril. So we took on a bit of that peril. When we got to Goulburn Square we did what they did - we sat down in the middle of the intersection, much to the chagrin of Sydney drivers, for 20 minutes and then we marched on to the hall. And as the ancestors had done we asked all the whitefellas to stay outside and we went in. Only blackfellas could go in to the hall, which is now the Mandolin Theatre. In that hall one of our number got up and read out the original manifesto from 1938.

We all knew that everything that was in that manifesto was just as relevant in 1998 as it was in 1938. We were still fighting the same battles. We had sent petitions to the New South Wales Heritage Council. We did so many things to stop that development application which was going to knock the building down. We wanted to keep it. And in the end we won the battle and got a permanent conservation order placed on the facade of the building. In advertising for that re-enactment we had posters made. This is one of the original posters from 1998, we had it done in the exact same format that the original poster was done in 1938. We tried to be to replicate everything to make it as powerful as we possibly could. Then in the end we finally won the battle. I sent off a petition to the Heritage Council which I would like to read out. I was pretty angry when I wrote this and I think it shows:

To Rajiv Mahi who was with the Heritage Council of New South Wales.

It is with immense sorrow that I learn of the proposed development of this enormously significant site. I am distressed to learn also that the Minister, Mr Craig Knowles, has consistently refused to place a permanent conservation order on the site. His reasons for not doing so can only be interpreted as meaning that he does not believe that sites of significance for Aboriginal people can exist in the built environment, which by extension suggests that Aboriginal people are relegated to the natural world of flora and fauna. This is extremely offensive as it denies our presence in the urban environment.

Further, the rejection of the site as a place of historical and political importance for Aboriginal people is to perpetuate the atrocities of the past where the true histories of this country have been sanitised. It seems that government authorities in this country will not be satisfied until every trace of an Aboriginal presence on the landscape has been erased.

This site has enormous significance for Aboriginal people in that its use by our fathers and mothers in 1938 marked a new direction in the struggle of our people to gain justice and equality for all Aborigines. On that day in 1938 Aboriginal resistance became politicised. Is this too much for you to bear? If so, then I suggest you put on a stiff upper lip and consider what Aboriginal people have had to endure in, and during, the colonisation of this country and are still doing so today. I will remind you of Hansonism, of Wik and the stolen generations. To deny our people of the very basic right to have one, just one, building in the CBD which we recognise as sacred and significant is to tell us that we do not rate as highly as the colonial garbage you immortalise in the permanent conservation order you placed on an incinerator.

I believe it is time that people in positions of influence and power took the blinkers off and recognised there is a world and a people out there who are no longer willing to sit in the gutter and accept the crumbs from the white man’s table.

I therefore call on you to reject out of hand the development proposal for the Day of Mourning site and turn this building over to the only people in this country to whom it has such spiritual, historical and political meaning.

(Applause)

We won the battle. The Lord Mayor of Sydney, the then Frank Sartor, put on a celebratory function at the Town Hall. My invitation to that function reads:

The Lord Mayor Frank Sartor requests the pleasure of the company of Ms Barbara Nicholson at a reception for the National Aboriginal History and Heritage Council to celebrate the permanent conservation of the 1938 Day of Mourning and protest site.

That is one of the proudest days of my life. The wonderful thing, and where I think there is an absolutely beautiful synergy, is that I did all that with that protest without knowing that my father had been one of the original protesters.

JOHN MAYNARD: That carries on the tradition, doesn’t it?

BARBARA NICHOLSON: You can’t kill the spirit.

JOHN MAYNARD: Absolutely. I think Barbara is a walking and talking memorial to the courage of her dad in the past and it has carried on through her. So power to you it is wonderful. I think we should applaud our panel. (Applause)

JOHN MAYNARD It was a wonderful insight. Again, the courage of the past is continued on through the descendants themselves.

We are now going to have Suzanne Ingram, Aunty Olive and Aunty Esther come up and speak about the 1938 Day of Mourning.

It is great to have you here to give that perspective on the Day of Mourning, the event itself, and for us to have an opportunity to have personal insight from family memories and how important that is. Suzanne, do you want to lead the discussion?

SUZANNE INGRAM: First of all, allow me to please also acknowledge the traditional custodians of this country on which I am speaking today. I wasn’t there in 1938. It came to be a bit of an important task for me to be able to acknowledge publicly that my family was involved in that. In 2004 I wrote an article which got published in our national Aboriginal newspaper the Koori Mail, and I got that story for that article from my Aunt Sylvia who is still alive, she is just not here. I was going to say she is not with us today, but she certainly is. But she stayed in Sydney. She doesn’t like the Canberra cold.

But remarkably too Aunty Sylvia remembers that day, but she wasn’t in the photograph. As far as we know, the only two people still alive today from that 1938 photo are these two women here. The reason I wrote the article is that I had grown up and my cousin who is here today, Aunty Esther’s daughter, grew up as did all our other cousins and extended family knowing that that was Nan and the aunties and uncles in that photograph. But after this - I think it was during this ice age - about five years ago I was doing some research on another project in Sydney about the Aboriginal heritage of Sydney Olympic Park and in the process of doing that research this photo kept on popping up at the Mitchell Library in Sydney. Then there was an open pictorial day about the photographs. Not only was there no names attached to the women and children in this photograph, but at one of the pictorial open days held at the State Library in Sydney a senior Aboriginal women, who was there with a group of young people, her students, tapped me on the elbow and said, ‘Oh, see that man there, that little boy there, I know him. He lives in the Blue Mountains.’ I thought, ‘Okay, this is going a bit too far,’ because that is my Mum’s cousin. These are two of my older aunties. My Mum is younger. I knew from Mum and also because I was very fortunate that out of all the family - my grandmother was the mother of 11 children so she had quite a few to choose from to live with - I happened to be the grandchild that I was very fortunate along with my brother to have her live with us pretty much most of my life. That through connection for me has been an extraordinary influence on my life.

But knowing that story, I knew that Uncle Nino wasn’t with us any more and I felt that this has to be corrected, this story has to go out. I trained as a journalist. I did my undergraduate degree in communications at Bathurst, which is home country for me, because home country for us is Wiradjuri country which is quite vast. It takes up most of what’s called now the central west of New South Wales and much of the Riverina. My grandfather is a Yorta Yorta man. He is no longer with us. He was from Cumeragunja and hence the reason why he was there. Again, I am getting all this story because of what I have been told, which I take to be truth.

And later after the aunts talk there is something I would like to present to you all today, which will be the first time it’s been presented. Because even though I have written this article and I have identified and spoken with my family and my aunties about it, there is a clique of historians who have point blank denied that that is who my family says they are and has constantly argued for further evidence because she can’t seem to find it in the written documents in the Mitchell Library. My first thought was obviously ‘well maybe you’re looking in the wrong place,’ but it’s not my job to tell a professional what to do. Four years down the track the poor woman is still no closer. I am happy to show it to you today, because that evidence has been around for actually longer than the 1938 photograph. Should we do it now?

JOHN MAYNARD: Do you want to have some response from the aunties and then show the image and talk to that?

SUZANNE INGRAM: I am sorry, I’m taking the floor. Yes, of course. Aunty, you’re on.

ESTHER CARROLL: First I would like to acknowledge the traditional owners. I am very proud to meet you again. A question was asked of me earlier, ‘What would have inspired Mum to be there on that day?’ Going back in my mind listening to the beautiful stories that were told here, I do recall some of the elders back on the mission, they were inspired also, I am pretty sure, by what was going on down here in Sydney. I do remember Mr Ferguson coming to Cowra many years ago but I thought they were - you know how the Christians used to go around with the conventions? - that is who I thought they were because I was too young at the time. But that is what they must have been doing, gathering all this support.

I do remember a guy who used to write political letters, Ernie Whitty, one of our elders on Cowra mission. I was pleased that somebody mentioned Pearly Gibb. She played a very big role and she worked for the protection board. Any information she got she used to filter it out to these men, which I think enabled them at that point to send word down to Cumera to prepare them that they were going to come down and remove the children, so I think they moved off the reserve overnight.

I was very pleased to hear from you, June, because I did meet three of your aunties and I think two of them are still alive - are they, June?

JOHN MAYNARD: I don’t think June is still there.

ESTHER CARROLL: Anyway Isobel McCallum was Bill Ferguson’s daughter and she was the first Aboriginal nursing sister at Prince Alfred Hospital, and I had the good fortune to meet these people. I was too little at the Day of Mourning, but the question I answered there was what would inspire my family to be there? I think they were all political, all motivated in some way but also inspired.

I got my inspiration when I got involved in the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs, and I think that is where we met Mr Horner. Charles Perkins inspired us to continue on doing what we were doing and to fight for what we believed in.

I am very proud - and who wouldn’t be proud - to be part of history like this. Good God, we didn’t know it at the time. (applause)

That is what somebody said to me: we lived to see the day. We didn’t think we would, because of our longevity or lack of it, but we did survive. At the time we knew we were in that photograph. We always knew that but we didn’t know we had to prove it. I am very grateful to you all for having the photo put up there like now. It is part of history and, my God, I am very proud of that. I am proud and I am pretty sure my offsprings will be too that it is history and the kids can be proud of it.

JOHN MAYNARD: Well said. I know Aunty is a little bit nervous, but it is great that Olive has stepped up to the front of the stage. Do you want to talk to the image that you have, Suzanne?

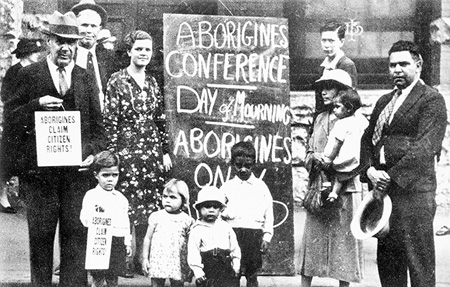

SUZANNE INGRAM: I would love to, if you don’t mind me showing it to you all. I will bring them both. This is the Day of Mourning photo.

This photo has been reprinted numerous times and I have often seen it saying ‘women and children unknown, the women presumed to be’ or are straight out named as ‘Mrs Selina Patten and Mrs Helen Grosvenor’, the women on either side. For Aboriginal people working in history and commemorating these kinds of thing, it is very important to us that you get the story right because, once an untruth is out there, it take as long time to kill it off. I am trying to remember the name of some old philosopher who said, ‘History is not just stories, it is what we base our truths upon.’ I just felt that it was really important. I also acknowledge, too, that ours isn’t the only one. I know there are other people whose involvement has been suppressed which is a bit silly. There are lots of people. You are not just a movement in one person.

When I first put this up - and I must acknowledge Mr Jack Horner because his publication and one other are the only ones that have correctly named the women and children in this photograph. As I say, about four years ago I did notify another area - which has won the New South Wales Premier’s History Award, might I add - that they actually had the wrong names there because they were regarded as either Ferguson or Patten children. To this day that has not been corrected and it has still been an argument which I have not just pressed but, well, here it is. If you can go and find other evidence then I am all ears for it, but that hasn’t happened. This is the 1938 photograph which was taken on 26 January, as we all know, and that is Aunty Esther, the little girl in the front, and that is Aunty Ollie.

OLIVE CAMPBELL: They asked me to march down and I said, ‘I’m too old. I’ve been doing this since I was 18 months old.’

SUZANNE INGRAM: She has done her share of marching. This is a photo from 1900 in front of the church at Cumeragunja. This is purely by chance, might I add. It is not as though Aboriginal people were running around with brownie box cameras in those days. What happened was they sent around people from government departments or from the churches to take a photo of the Aboriginal people in front of the church.

This photo was taken at Erambie mission, Cowra and is dated. It says: ‘May 12, 1937, Coronation Day, Cowra Aboriginal station’. Aunty Esther in this photo is being nursed by my grandmother Louisa Ingram, and Aunty Ollie is being nursed by the eldest sister, that is Aunty Sylvia who was the source of the story for the article. The two boys are Uncle Choco or Uncle Phillip and Uncle Ike. Kids don’t really change - they do change a lot, but these are only six months apart. As I say, this evidence has been there but I have been constantly asked for the past four years, ‘prove it, prove it.’ I thought, ‘If you are half as good as you say you are, you should be able to find it yourself, you don’t need me.’ I invite you please to come up and have a look at these photos.

It was quite funny, because I didn’t have a really good copy of this picture until I picked Aunty Ollie up on the way down to Canberra yesterday, because you wouldn’t have been able to make it out in the photo I had. And for me that’s what it is all about, because you have a lot of people who are informing on Aboriginal history. There are a lot of informants. How do you know that they know what they are talking about? How do you know that they’re not just spinning you a yarn? For us it is not that I need to come up here and thump my chest that that is my family. It is because as Australians you deserve to know the real truth, not something that has been filtered through something else because the written evidence isn’t there.

But just to get back to why I picked this photo up off the wall for me that is where you will find it. You will find it through talking with Aboriginal people. You will find it through picking up the phone and making a phone call or asking around, because there will always be somebody that knows somebody. In fact, that is how Link-Up works. That is one of the reasons why we always know who’s who and, if you don’t, then there is a question mark about you. The other thing is that, if you are ever invited into someone’s home, you look at the photographs because that is where the stories are and you will always find those things there. I don’t know any Aboriginal person who won’t talk. They might be a bit suspicious of you first up but, if you want to know, that’s what I found most definitely.

ESTHER CARROLL: People are quite welcome to look at that later because you might be a distant relative of some of them, because there are Bambletts, Murrays, Williams, a whole range of Aboriginal people.

SUZANNE INGRAM: And that is how we understand each other - we recognise the clan names because the clan names are place. My children for example have taken their ’s name. My ex-husband is a third generation French-Australian, so my children carry the name Bagent. There aren’t any Aboriginal Bagents apart from them. So in order for them to be identified through other Aboriginal people, they have to be asked: So who is your family? They will always say Ingram and everybody knows that you must be from Cowra. That is how it works. It is the same if you meet someone with the surname McKenzie, you can be pretty sure -and you will ask them - that they are from Walgett in the north west or somewhere up that way. That is why it is very important that the names are attached to the faces, because the faces are attached to the places, and places are land, and that’s where we come from.

JOHN MAYNARD: I think there is an important point, Suzanne. You said there is not a written record but you drew attention to Jack, and we are honoured to have Jack in the audience here. Jack and Jean [Horner] were such great campaigners and supporters of Aboriginal people for such a long time, and Jack’s book [Bill Ferguson: Fighter for Aboriginal Freedom, 1974] is an absolute landmark. As Jack has named the children in that book it is in the written record, and Jack goes back many decades before and was speaking to the people who were there and who had insight into that event. So there it is in the written record as far as I am concerned. That is beyond argument. No-one had more attention to detail than Jack. Certainly the book that Jack wrote still stands today as great testament to Jack and also the people that were providing the information and the knowledge to Jack through their memories which Jack wrote up.

SUZANNE INGRAM: I agree. I guess what the ice age kind of represents is selective kind of histories, and for me that doesn’t fly because everybody has a story. There were lots of people who were involved.

JOHN MAYNARD: Do Aunty Olive and Esther want to make any other comments on the day or their memories of what it has meant to them to carry that memory through their lives together?

OLIVE CAMPBELL??: I am very proud and very honoured to be here. We were only babies, and you are putting us with very distinguished people that are a part of history. We weren’t active but I am very proud of the fact that my parents were, that they saw fit to be there and support it the way they did. I think we do get a little bit of that from our parents, but from Mum in particular, because we have challenged the system over the years. If it didn’t work for us, we challenged it.

ESTHER??: Dad was down at the Domain -

OLIVE??: The only time I have seen that photograph was in Mr Horner’s book and over the page there was one where they were down at the Domain. The men were down there with the tarpaulin muster, you know, and I think they were the fundraisers. Well, Dad was part of that. The eldest girl Sylvia was out at La Perouse with our grandmother, Dad’s mother - I have got all my names mixed up now. Louisa was my mother, Isobel was my other grandmother but Elizabeth Bamblett - she took Sylvia out to La Perouse for that throwing in that day.

SUZANNE INGRAM: Grandfather is in this photo as well, the missing man that is not in that photo.

OLIVE??: That is why he wasn’t on that photograph on that day.

SUZANNE INGRAM: As I say it has been commonly noted as ‘women and children unknown’, it is really interesting that the women have not been identified for such a long time in the public record, which is a bit crazy really because they are such a big part. Everyone who has been speaking here today, apart from poor old John, have been women.

JOHN MAYNARD: A bit of gender imbalance here.

SUZANNE INGRAM: I was speaking with one of the curators here, Kipley, and I think it was because I raised it. AIATSIS had talked about it being the 70th anniversary and the names again were missing. So I shot off an email. Each of them had to satisfy themselves that I am not spinning them a yarn, and absolutely that is what I expect you to do. That is how that came about.

ESTHER??: I know my grandkids and great grandkids are going to be proud.

JOHN MAYNARD: What’s also important here with 1938 - it is 70 years - is that it didn’t end there. But what stalled the movement was the onset of World War II at that particular moment. Aboriginal activism didn’t finish then either. It continued through the 1950s and into the 1960s. Significantly though, non-Indigenous historians and the wider community largely believe that Aboriginal political activism began in the 1960s.

It is very important that we recognise those events of the 1960s. Charlie Perkins with the freedom rides picking up a whole bunch of non-Indigenous students and lobbing them on a bus and going around and exposing the horrific conditions that were impacting on Aboriginal people in communities and putting that through the media to the wider populace of this country. Then there was the Gurindji walk-off at Wave Hill in 1966. The Gurindji were masters of the media. They also had great support from the trade union movement in 1966. In the 1967 Referendum 92.7 per cent of the population voted with Aboriginal people in 1967. I might add that the vote went the opposite way in Kempsey, which does explain something of the situation in Kempsey, even today. Then there was the tent embassy in 1972 and the 1988 Bicentennial.

These are all important events but history goes back much further. Certainly with the Day of Mourning and these particular activists of this time period need wider acknowledgement in the non-Indigenous community and their place in history as far as they are concerned. I will certainly give an insight into my grandfather as well in relation to that.

ESTHER CARROLL??: Can I just add to that: one of my younger sisters, leading up to the referendum when they got mostly young people from the foundation to go out and get as many Aboriginals identified, she knew that her neighbour was an Aboriginal. She went out and asked would she give her support and she put the dogs on her saying, ‘I’m not Aboriginal.’ Also with the tent embassy, when they first set it up they had to move and build a new one. My brother and his mate who was a brother to Ned Simpson - who you Canberrans would know - his brother Neil Simpson and my brother Lachlan Ingram sat there and kept that tent embassy going and let his wife battle up there with the kids. They kept it going until the other fellows come down so that it wasn’t lost. What I go on about is that we should acknowledge those who have contributed - don’t forget them.

JOHN MAYNARD: Absolutely that is the crucial point. We will keep questions until later. I might give a quick overview of my grandfather and the 1920s movement and then we will move on to questions from the audience. We will leave the panel here and the other panel members might want to contribute as well. I am similar to the other descendants in the fact that I take incredible pride and inspiration from the memory and legacy of my grandfather and not just in the way I conduct myself in academia, which is still a foreign zone as far as I am concerned for me. Like a lot of Aboriginal people of my generation I don’t have fond memories of the school years. I started school in 1959 and I left in 1969. There was nothing for me in that school curriculum, history or culture, nothing to connect with, and I got out the door as soon as I possibly could.

For the next 25 years I worked in many jobs such as barman, truck driver, builders’ labourer, hairdresser, on-flight groom looking after racehorses flying around the world - a whole host of jobs. But one thing that stood me in great stead was I was an absolutely ballistic reader particularly of history and I consumed an incredible amount of literature. I think in some sense I educated myself. I went to university just shy of my 40th birthday not by design but basically by accident.

My grandfather was a high-profile Aboriginal activist of the 1920s. Fourteen years before the Day of Mourning protest, the APA and the Australian Aborigines League he formed the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association which formed in Sydney in 1924.

I went to Newcastle University just because I was putting some family history together of my grandfather’s story for my father, my uncles and aunties, cousins and extended family members. That was the limit of what I wanted to do. I went to Wallatooga, the School of Aboriginal Studies at Newcastle University. The then director was Tracey Bunda, a Murri woman from Queensland, and I had the briefest of words with Tracey. By the time I turned around I had been kidnapped and I was suddenly enrolled as a university student - I am still scratching me head about that - and I still owe her immensely for that encouragement she gave me. I did a diploma, then I completed a BA and subsequently a PhD, and five books later I am a professor. It’s been an amazing journey. I am the first member of my family to go to university.

My father was an Aboriginal jockey, which is another book I have written about, which is about Aboriginal jockeys. I had been at university two weeks in the diploma course and another old fellow at the race track at Broadmeadow in Newcastle said to my father, ‘What’s John doing these days?’ And the old man said, ‘He’s over at the university.’ And the other fellow said, ‘What’s he doing over there?’ My father said, ‘Oh, I think he’s a professor or something.’ I had been only been there two weeks as a diploma student. But he must have had incredible insight because eventually down the track that’s what did happen to me.

This talk is a little bit of shameless self-promotion of my book Fight for Liberty and Freedom about my grandfather and the 1920s Aboriginal political fight, which has only just recently been released. Gary Foley and Jeff McMullen launched the book in Sydney, and I have basically been doing talks all around the place. Gary Foley had a launch down at Melbourne Uni and I spoke at Eltham Book Fair and the Sydney Writers’ Festival and the Greening Festival - I’ve been everywhere, a bit like that song. But it’s been an incredible journey for me, particularly from my educational background which was extremely limited in my school years, I have to say. I didn’t receive much encouragement at school.

My grandfather’s memory and organisation has been forgotten and erased in many instances, I believe, as far as that particular movement was concerned. And that is incredible because the work that I have done has divulged, exposed, the incredible impact they had at that particular point. Non-Indigenous historians have gone on for quite some time that the early Aboriginal political movements were basically led by non-Indigenous Christians and humanitarian groups. But this particular group in the 1920s was all about black nationalism. The people that influenced my grandfather were people he had come into contact with: Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight boxing champion of the world whom my grandfather met in 1907 and 1908 in Sydney when Johnson was here and actually won the world heavyweight title.

My grandfather was a dock worker in Sydney, as were many other Aboriginal men, as Barb related with her dad. That is where a lot of political fire come from with their experience on the docks and their connection with the trade union movement. When my grandfather was working on the docks in the World War I period they were very confrontational. They challenged Billy Hughes’ conscription policy and they actually beat that referendum. Then there was the Marcus Garvey influences. Today Garvey is recognised as leading the biggest black movement ever established in the United States because it influenced Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Elijah Muhammad, the Black Panthers. This organisation was centred in Harlem and was operational from 1916 through to the mid-1920s until Garvey was jailed by the US government and then deported because he was a West Indian.

People like my grandfather in Australia who came into contact with African Americans, West Indians, South Africans gained their manifestos from documents about what was going on in the global struggle of oppressed people, particularly black people. This made a big impression on people like my grandfather. With the ideology of Garveyism, a lot of scholars today seem to say that Garvey was all about going back to Africa. Garvey never ever said that, other than in a spiritual sense that blackfellas in the United States should look to a spiritual home. He said in a spiritual sense that you need to connect to your homeland. That had a big connection with Aboriginal people here in this country, I have to tell you - you need to be connected to your country.

Also the incredible strength of the Garvey message was all about take pride in your own history and take pride in your own culture. This resonated powerfully with Aboriginal activists, and they incorporated a lot of Garveyism into what they were actually saying. My grandfather and other Aboriginal activists in Sydney of this particular period actually joined Garvey’s organisation. They were part of a chapter operational in Sydney from 1920 to 1924.

Then in 1924 they moved away from that and they formed their own organisation, the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association. They had obviously realised that they needed to put it in an Aboriginal context, and that was the best way to take the fight up. Their message, their manifesto, their platform was that they wanted enough land for each and every Aboriginal family in the country. This was sent to state governments and to the federal government. It was published widely right across New South Wales but also the message went to Queensland, Victoria and even South Australia. And it was also published in the United States, from stuff that I uncovered over there. It was a very strong message that was not recognised.

They also fought strongly that the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Board’s act of taking away Aboriginal kids from their family had to be stopped. They wanted to defend the distinct Aboriginal cultural identity. They wanted the complete abolishment of the Aboriginal Protection Board and wanted it to be replaced by an all-Aboriginal group to run Aboriginal affairs.

The Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association held four conferences, the first in Sydney in April 1925 at St David’s Church and hall in Surry Hills. Over 200 Aboriginal people were in attendance. They were front-page news in that particular incident. I will just read a very short piece of that particular conference, which again challenges the right-wing extremists who tend to think that Aboriginal political activism began in the 1960s with the Windschuttles, the Pearsons, the Acamas and all those people and that the whole push for self-determination began in the 1960s and 1970s led by the Whitlam government. The front-page newspapers in 1925 said on Aborigines’ aspirations, ‘First Australians to help themselves: self-determination’ and another headline ‘Aborigines in conference: self-determination is their aim to help their people’. [FN 1]

My grandfather as the president began his inaugural address with the words, ‘Brothers and sisters, we have much business to transact so let’s get right down to it.’ And he went on to say, which was recorded in the press at the time:

We aim at the spiritual, the political, the industrial and the social. We want to work out our own destiny. Our people have not had the courage to stand together in the past but now we are united and are determined to work for the preservation for all of those interests which are near and dear to us. [FN 2]

Their second conference in Kempsey, again in 1925, ran over three days. All the papers delivered were delivered by Aboriginal people, all Aboriginal organisations. They had 11 chapters of the organisation with over 600 members, but 700 people were there at that conference in Kempsey in 1925. The papers were about health, kids, land, children, education - a lot of the stuff we are still fighting for today, they were fighting for then. My grandfather delivered a powerful resolution, which was sent to the New South Wales Premier at the time and published widely in the press in New South Wales, which resolution closed the conference. He said these words in the resolution:

As it is the proud boast of Australia that every person born beneath the Southern Cross is born free irrespective of origin, race, colour, creed, religion or any other impediment, we the representatives of the original people in conference assembled demand that we shall be afforded the same full right and privilege of citizenship that is enjoyed by all other sections of the community. [FN 3]

These are extremely powerful words in the mid-1920s. If you go through the history of the anthropologists, Aboriginal people belonged to the stone age - we were a dying race; we couldn’t be educated; they were going to ‘smooth the dying pillow’. This particular material quite clearly shows that these were articulate, eloquent, educated Aboriginal men and women, statesmen and women. Suzanne touched on the fact the movement very heavily involved women all the way through it. This was not an Aboriginal men’s club here, and that’s been the case of all of our fights throughout history. We stand together in that sense.

The organisation had another conference in Grafton in 1926, and another one in Lismore in 1927. Their manifesto in 1927 went to Jack Lang, the Premier of New South Wales, and again it hadn’t changed over a three-year period, it concerned land, children, culture, Aboriginal people being in charge of Aboriginal affairs, and the abolishment of the Protection Board. The Premier sent it back to the Aborigines Protection Board for their thoughts and their response was: ‘Fred Maynard is a man of illogical views who will do more harm to Aboriginal people, and the Premier is not to occupy his time unduly with this radical viewpoint.’ They didn’t send that response to my grandfather, but the response that came through was basically that Aboriginal affairs was going to be left in the control of the Aborigines Protection Board, and he knew quite well that the protection board had interfered.

My grandfather wrote a three-and-a-half page letter to Jack Lang, which I think still stands today as one of the most powerful ever penned by an Aboriginal activist. I certainly won’t read all three and a half pages here but I will read a short piece out of that letter that he directed to Jack Lang in relation to the government taking no notice of Aboriginal demands. In the letter he said:

I wish to make it perfectly clear on behalf of our people that we accept no condition of inferiority as compared with the European people. Two distinct civilisations are represented by the respective races. On the one hand we have the civilisation of necessity, and on the other the civilisation coincident with the bounteous supply of all the requirements of the human race. That the European people by the arts of war destroyed our more ancient civilisation is freely admitted, and that by their vices and diseases our people have been decimated is also patent. But neither of these facts are evidence of superiority. Quite the contrary is the case.

The members of the AAPA have also noted the strenuous efforts of the trade union leaders to attain the condition which existed in our country at the time of invasion by Europeans. The men only worked when necessary. We called no man master and we had no king. [FN 4]

What an incredibly powerful statement that was delivered at that particular time period 80 years ago. We are highlighting today that it is 70 years since the Day of Mourning. It is also 80 years since my grandfather’s organisation disappeared from public view when they were basically hunted and hounded out of existence by the police acting for the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Board. That story is in the book.

I will close with a short extract from another long letter my grandfather wrote. The AAPA established a very strong Aboriginal community network. My grandfather wasn’t allowed to go on to Aboriginal missions or reserves. The reality was the protection board said he was inciting revolt. But the community knew when he was about, and fortunately in years gone by I had the good fortune to do interviews with some of the kids who actually ran off places like Bellbrook with messages to my grandfather. The community knew when he was about. Kids would run off and they would have messages of ‘what the hell was going on’ to people on the reserves during the 1920s and they would meet my grandfather under a bridge.

One of the messages that got through to Sydney to my grandfather in 1927 involved a young Aboriginal girl 14 years of age being taken from her family and sent to Angledool in western New South Wales where she was repeatedly raped by the mission manager and she became pregnant. The protection board bunged her on a train and sent her to Sydney. She had the baby. The records say that the baby died - we are not to know that. The baby may well have been removed and given away to someone. The girl was immediately put back on the train and sent back to Angledool, the place where the abuses happened.

When this message reached my grandfather - and I have said this many times - no matter how many times I read this letter, I always get moved by it because it is so powerful and so moving. This is how he began this letter:

My darling little sister, I am speaking to you now as a big bro’ [this is 1927]. What a wicked conception, what a fallacy under the so-called pretence at administration re the board, governmental control etc. I say deliberately the whole damnable thing has got to stop and by God’s help it shall.

I may tell you, and listen girly, your case is one in dozens with our girls. More is the pity. God forbid those white robbers of our women’s virtues. Seen to do just as they like with downright impunity and, mind you my dear girl, the law stands for it. There is no clause in our own Aboriginal Act which stands for principles for our girls. That is to say, any of these white fellows can take our girls down and laugh to scorn yet with impunity that which they had been responsible for they escape all their obligations every time. These tyrannious methods under the so-called administrative laws re the Aboriginal Act have got to be blotted out as they are an insult to intelligent right-thinking people. We are not going to be insulted any longer than it will take to wipe it off the statute book. That is what our association stands for: liberty, freedom and the right to function in our own interests. Are we going to stand for these things any longer? Certainly not. Away with the damnable insulting methods which are degrading. Give us a hand. Stand by your own native Aboriginal officers and fight for liberty and freedom. [FN 5]

Sadly, the girl never received the letter. The manager opened the letter, and it was sent back to the Protection Board and the New South Wales government who intensified their attacks against my grandfather not just in the press but also on the street. The Aboriginal organisation disappeared from public view in 1928, hounded out of existence by the police.

They didn’t stop their agitation. Interviews with uncles, aunties, my father and other people connected to the organisation. So they continued to hold meetings at Sid Ridgeway’s place which included Dick Johnson, Tom Lacey, Sid Ridgeway and my grandfather. My grandfather bobs up continually in records at La Perouse in the early 1930s, and the La Perouse community said they had aligned themselves with the AAPA. One old uncle I interviewed probably 15 years ago was a greenkeeper at the University of Sydney in the early to mid-1930s, and he said the last time he heard my grandfather speak was in the grounds of University of Sydney in that particular time period.

Interestingly enough, with the government inquiry that came up in 1937, there is a letter in the archives - Bill Ferguson and Pearly Gibbs did speak at that inquiry - that was sent particularly to the Protection Board and to the government to say names of people who should have the opportunity to speak. Johnny Donovan, a very highly respected member of the Nambucca community, was one of those people whose names were put forward. Jimmy Doyle was another, Gary Foley’s great-grandfather. And my grandfather - in this letter it said ‘Fred Maynard, an Aboriginal man from Lakemba, should be given opportunity to speak.’ None of those people were allowed to speak. None of the 1920s group were ever seen visible in the late 1930s, particularly with the Day of Mourning. The levels of harassment by the police were so severe on these people that they were driven underground.

Taking it back a little bit further, in 1928 my grandfather married my grandmother, a white woman. Now in 1928, without argument, my grandfather was the highest profiled Aboriginal activist in the country at that particular point, but he had stepped across a boundary which would certainly have troubled non-Indigenous Australia. For an Aboriginal man to marry a white woman it was taboo. It was okay for white men to abuse Aboriginal women wherever and whenever they wanted if they could get away with it, and they got away with it a lot. But for an Aboriginal man to marry a white woman at that particular time period was very confronting. I might add that my grandmother was not from a privileged background. She was from a mining family who had come from Bolton, England, and had gone up to the coalfields in Cessnock. My grandmother was working at a coffee shop on central station and was a single mother when she met my grandfather. Unbelievable - it is not unbelievable; I suppose it was the stigma of the day - in marrying my grandfather her own family ostracised her completely. She was cut off from her own family for marrying an Aboriginal man at that particular point.

The organisation of the AAPA disappeared not just in the time period but also in memory. My grandfather - the stories are that he had an accident on the wharf. He was in and out of hospital for 12 months. One leg was broken in six places. He contracted sugar diabetes which affected his mind. Gangrene set in and his leg was removed. He died eight years before I was born, so I never had the opportunity of meeting this remarkable Aboriginal patriot. As I said, the stories go that it was an accident and I certainly think it was not an accident - as the book tells that story. It’s an incredible story of what happened to my grandfather then at that time because he wasn’t in the public arena. Was it something to do with Aboriginal issues, him still being outspoken, or was it something to do with the working on the docks? I will probably never found out but I certainly have my own feelings.

But for me, being descended from my grandfather just gives me such - and we find that here with all the descendants - incredible pride, courage and strength. Everything that I have done and continue to do in my life is the respect that I carry for his memory. And certainly all of those people, and the people from 1938 and the people in the 1950s and 1960s, they had incredible courage to stand up in their particular time periods.

In closing for me the legacy, and I think that goes for the 1930s group as well, the reality is the demands made then. My grandfather’s demands in the 1920s, if it had been met in 1925 that enough land had been granted to each and every Aboriginal family in the country, we wouldn’t be in the situation now of such horrific disadvantage economically for every Aboriginal family basically in the country where we start behind the eight ball. If the demand had been met in 1925 that the Aborigines Protection Board stop the policy of taking Aboriginal kids from their families, we would not have had to endure another five decades of that horrific policy where thousands of Aboriginal kids were removed. If the demand to protect a distinct Aboriginal cultural identity had been met then in 1925, we wouldn’t be in the process of putting this jigsaw puzzle back together of our culture and of our language. If the demand had been met that the Protection Board was scrapped, we wouldn’t have had to wait until the 1967 Referendum to get rid of it. And if demand had been met that Aboriginal people themselves were the best people to take charge and direct Aboriginal affairs, we would be in a far different place today. That is my talk and thanks very much. (applause)

Would people in the audience like to open up with questions and discussion?

QUESTION: Hello, my name is Delphine Fraser. At the age of six months I had re-voting in Gough Whitlam pamphlets in my purse so very much a political foundation. Secondly, Oh my God, thank you. As an Indigenous woman who politically driven everything - the foundation of women and a man standing in front of me is incredible. It is to you and to your family, just even sitting here looking at you.

I am a 1974 model. I was born in 1974 of April and I find it a very interesting year. I have heard it mentioned a couple of times. It was a time where things were progressing but also things were kind of stagnating. To me I lived for quite a time in the Northern Territory. There was a topic of synergy here. I find it very interesting now with the NT invasion - not intervention, it’s an invasion, be real about it. How are they going to record this honestly? NT blackfellas need to put some form of foundation in like this other mob, because in 20 years what we are suffering now - loss of language, loss of land, loss of that - they’re going to be suffering. My thing to me is very much a close watch on the NT invasion.

I am so excited to be here. I think it is very important and also just making things known. Living in NT we would have to go visit mob in the hospital. And one thing when you go visit a Northern Territory hospital, you notice the blackfellas sitting all around the outside. To me that is a deliberate act. To me they turn the air conditioners down so low that blackfellas can’t bear it. And if you know blackfella - like Aunty said, ‘she can’t come to Canberra, she too cold.’ They are climatised to their point. It is this recycling of things and not being real about it. If they are real about it in NT health, why don’t they put an open air hospital in there so the mob can sit in there and air con don’t chill them. I just wanted to make those couple of notes. But Oh my God, thank you. Can I get your details, on the left. I didn’t get your name, I am sorry. I would like to be in contact with you with my studies and with also Mr Maynard. And I know Tracey Bunder too. Ain’t she deadly!

SUZANNE INGRAM: Can I just comment on what Delphine just said. In Sydney my mother was heavily involved just recently with a support group for a group of women from Alice Springs who were trying to speak out against the intervention because the media has been pretty much in control of a lot of the argument. It was interesting that she had a lot of support from university students - international and regular Australian students. I remember sitting there watching them all together at the one time. Mum I have not seen her - I have seen her passionate about a lot of things but this one was one of the things that I hadn’t seen in her for such a long time. It dawned on me that it is because the whole intervention for her is this nightmare of growing up on the missions all over again - to have your income quarantined, to be told where you can and can’t go, and particularly the demonisation of men. My brother and my son are Aboriginal men. Excuse me, but they are not molesters, they are not rapists. There is no balance in this horrible story.

SPEAKER (inaudible)