Howard Morphy, John Carty and Dr Michael Pickering, 8 December 2010

MIKE PICKERING: We have rung the bells and closed the doors so we can begin. My name is Mike Pickering. Thank you all for coming to see me today. It’s a great turnout for what should be a very interesting discussion revolving around two very interesting exhibitions. Quite clearly I am biased for the exhibitions but I think you will agree that the bias is justified.

First of all I would like to acknowledge the Ngambri and Ngunnawal peoples of the ACT and surrounds who are crucial to the National Museum of Australia’s operations. They are partners in everything we do and has certainly been supported by Matilda House’s very generous welcoming of the artists for Yiwarra Kuju and also for Yalangbara here to Canberra. It is greatly appreciated by the Museum and greatly appreciated by the artists to know that they are welcome on Ngambri and Ngunnawal country.

The event is being recorded for our audio on demand program. We will be having a question and answer session at the end, at which time we will have a roving mike. Would you please wait until the microphone is brought up to you before you start talking and wait until the mike is there, otherwise the question won’t appear on the recording and it just leads to breaks.

As the MC I do have the advantage of being able to throw in a few statements. I think these exhibitions are fantastic not just because I work here but because they are so full of rich, cultural information and they tell stories. I don’t want to pre-empt the speakers who are going to address the exhibitions and what they have in common and their differences in much more detail, but I will say they are not just one-themed exhibitions, they have many themes including relationships to country, relationships with the dreaming and sacred ancestors, relationships with family, relations with place but also changes in art styles which reflect a continuing tradition of changing.

I am also capable of throwing in a few questions without expecting immediate answers. One is the concept of Aboriginal art as ethnographic. It has been de rigueur to condemn people for treating Aboriginal art as ethnographic, but I am curious about when did ‘ethnographic’ become a dirty word since all art is ethnographic and it does or should tell something about the cultural and social contexts of the artists.

The other question I have is why do ‘we’ – I am very generous saying ‘we’ when I mean art galleries and art collectors in particular – impose Western taxonomies on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art. Just because something looks abstract doesn’t mean it is. I already have answers to these questions, and not surprisingly they agree with my own opinions. But I like to think that in these discussions we can throw up some curly questions to our two speakers here and see what we can stimulate.

I don’t think our speakers need introduction to anyone who has been involved with the Museum. We have Professor Howard Morphy, a national and international expert in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art. He has written extensively on the subject matter, and I recommend Howard’s writings to everyone because they are so easy to read. The language is not obscure. If you go and get a book and you want to actually understand what the anthropologist is saying, Howard is excellent in my view for a public audience.

Then we have John Carty. John is both a student and a professional and practising anthropologist. He was a critical co-curator in the Canning Stock Route project Yiwarra Kuju and is now working for the Museum while studying. As I said before in private, I don’t want to intimidate John – he can speak openly and freely at this discussion knowing that his entire future rests in the hands of Howard and myself. On that basis I would ask you all to get your pens and paper for writing down questions that you want to ask and open up the discussion and hand over to John.

JOHN CARTY: There is no pressure there, is there? Okay, understanding Aboriginal art in ten minutes, which is what I was given but I am going to try to get a bit more out of Mike through some sweet looks and batting my eyelids halfway through. This is going to be a long ten minutes because I’m going to start by stating, unequivocally, that we do NOT understand Aboriginal art; or rather often we don’t understand it in the way that artists hope we will or that they allow for us to do so. That’s because we don’t really understand what is that people are painting. We don’t understand Country.

I think Yalangbara and Yiwarra Kuju are two exhibitions that seek to help us to see, to understand but for me most importantly to feel the importance of Country. I can’t comment in detail on Yalangbara. I have only seen it for the first time yesterday, but the resonances with Yiwarra Kuju are quite extraordinary in many ways. I can’t even comment in any detail in this nine and a half minutes on Yiwarra Kuju. What I want to do is use one or two Western Desert paintings from the Yiwarra Kuju exhibition to open up the terrain and the conversation that that exhibition and also I think Yalangbara addresses.

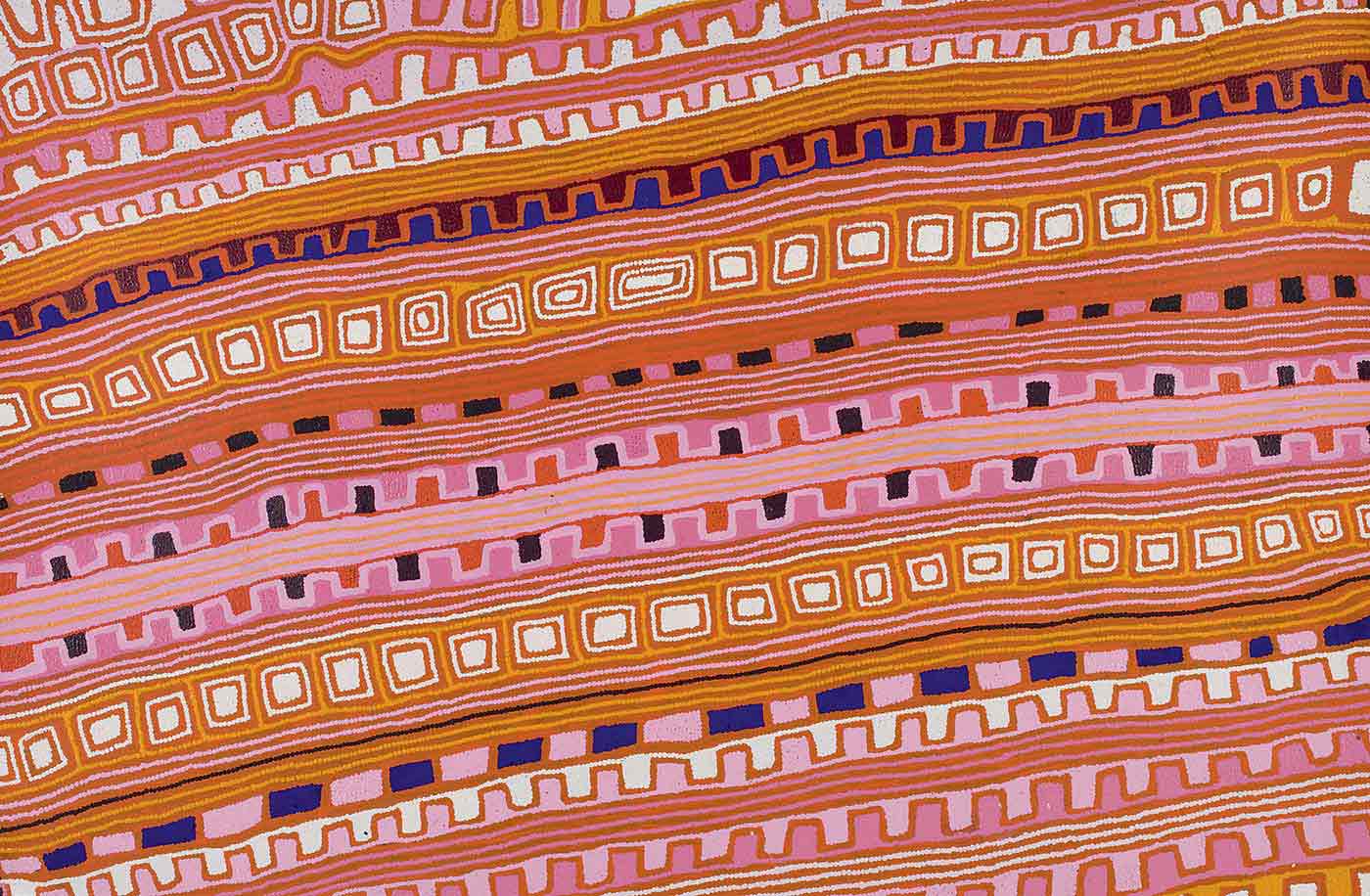

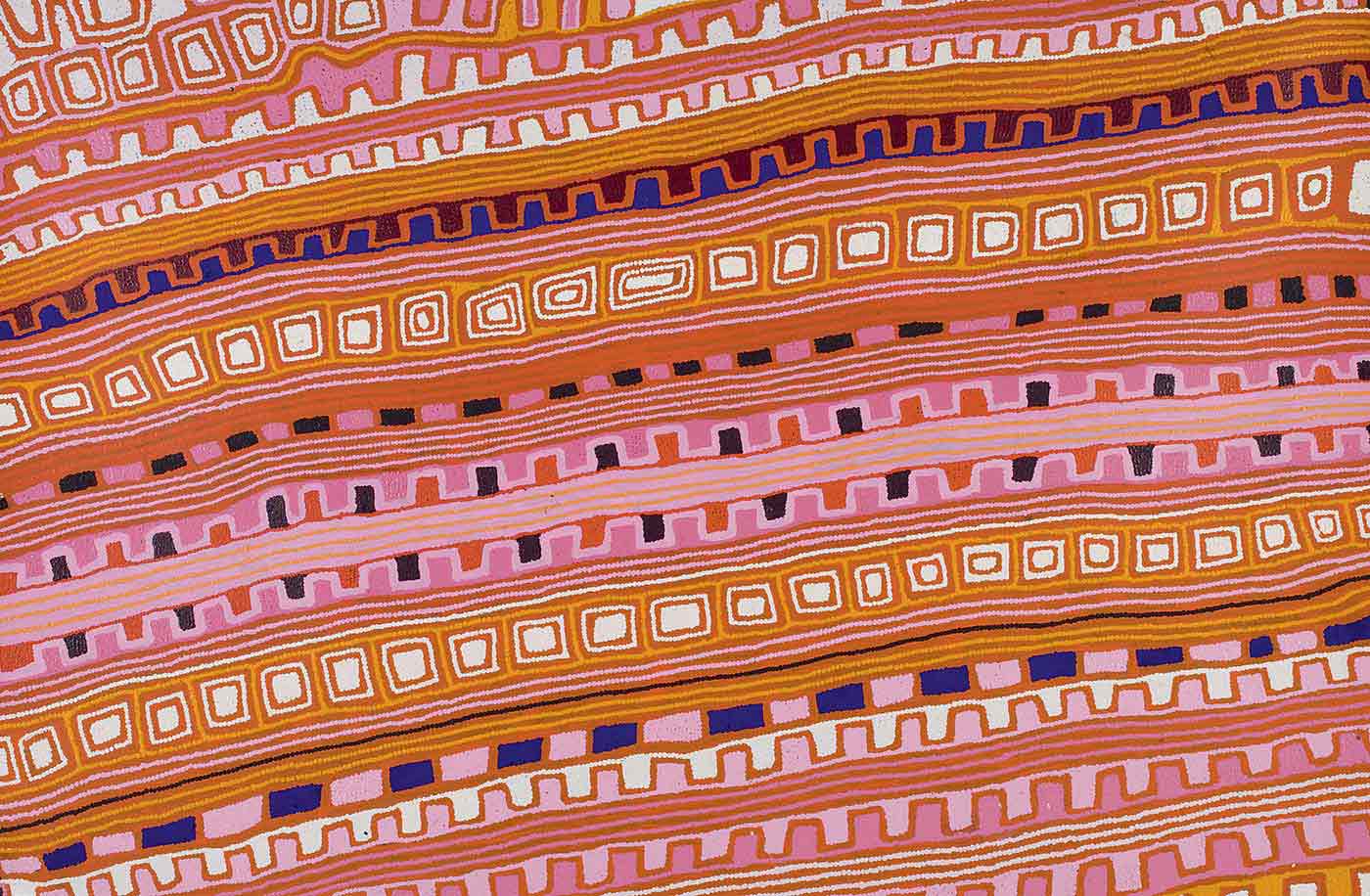

One painting I want to discuss is this big pink beauty by Patrick Tjungurrayi [image shown].

It’s a classic example of contemporary Western Desert art, painted by one of the most acclaimed painters of our times. It is also impossible to understand just by looking at it. This is not a comment on the inscrutability of the art work, as you will soon see, but a reflection upon some conventions that attend and obscure the reception of Aboriginal art.

Fortunately, not knowing what Mike was going to say, I think I am about to agree with him. For the past 30 years if not longer, curators, collectors and writers have fought hard to have Aboriginal art recognised as fine art, as contemporary art, as the equal of any great art produced anywhere at any time. Apart from a few rogue nations still grappling with their own primitive instincts, I think we won this battle. Yet the battle lines endure.

Part of that battle over the past decades was about distinguishing ‘art’ from the ethnographic objects analysed by anthropologists and collected by museums. Art belongs in a gallery, and these objects are to be treated differently; they will mostly be on white walls with minimal text or context to detract or distract from the power of the aesthetic art object. In recently opening the most important and expansive display of Aboriginal Art in this country, the Director of the National Gallery of Australia, Ron Radford, reiterated the divide that the art world positions itself against:

The galleries are rooms consciously and unapologetically designed for the permanent collection of Indigenous art, not for anthropology …

We are inhabiting an interesting moment in history of Aboriginal art right now – I think Howard might argue that that moment has been going on for some decades. It is not something that I have discovered today. It is a moment in which the tensions between anthropology and art, between galleries and museums, their roles and ideologies, are being played out on the shifting terrain of painted Country. What we want to avoid in this though is an institutional fixing of positions, particularly one where art requires a white wall and ‘anthropology’ is positioned as a murky synonym for content.

My concern here is not to defend anthropology but to defend art from the complacency that often attends equality. It is risky to assume that simply because Aboriginal art has become part of the furniture in our galleries and in our homes that we somehow understand it any better than when it wasn’t. It is not accurate or helpful to conflate the content of a painting with some ‘ethnographic’ framework – as if these modes of understanding were somehow inherently opposed to the intent of the artist.

The intent of most Western Desert artists that I know is to show us their Country and the expectation, generous but often grossly mistaken, is that by seeing these paintings we somehow understand the importance and complexity of that gift. To be shown something in desert culture is to have knowledge revealed to you. It is a gift, but often an inscrutable one. I can’t count the number of times desert friends have taken me to an important place and said after two seconds there, ‘You’ve seen it – now you know,’ and little green anthropologist sitting there going (shrugging), ‘There’s no rule book. I don’t understand. I don’t know,’ and I think it’s the same with art.

The premise of the Yiwarra Kuju exhibition is that we use a non-Indigenous road, the Canning Stock Route, as the meeting point, as the cross-cultural scaffolding on which to develop an understanding of Country. Yiwarra Kuju is as much about curating an audience as it is about curating an exhibition.

To understand Australian history, you have to understand the Country that it happened within. To understand these paintings, you have to understand – in some way – the Country they depict. This exhibition doesn’t teach people about history or about art, but it equips them with some basic entry points and tools for understanding Country, which is still an elusive concept to so many us, anthropologists included. Through Yiwarra Kuju we try to give people some common touchstones such as the family, the Dreaming and just the simple concept of home to help them pull apart this idea of country and recognise themselves and their own understanding of the world within it.

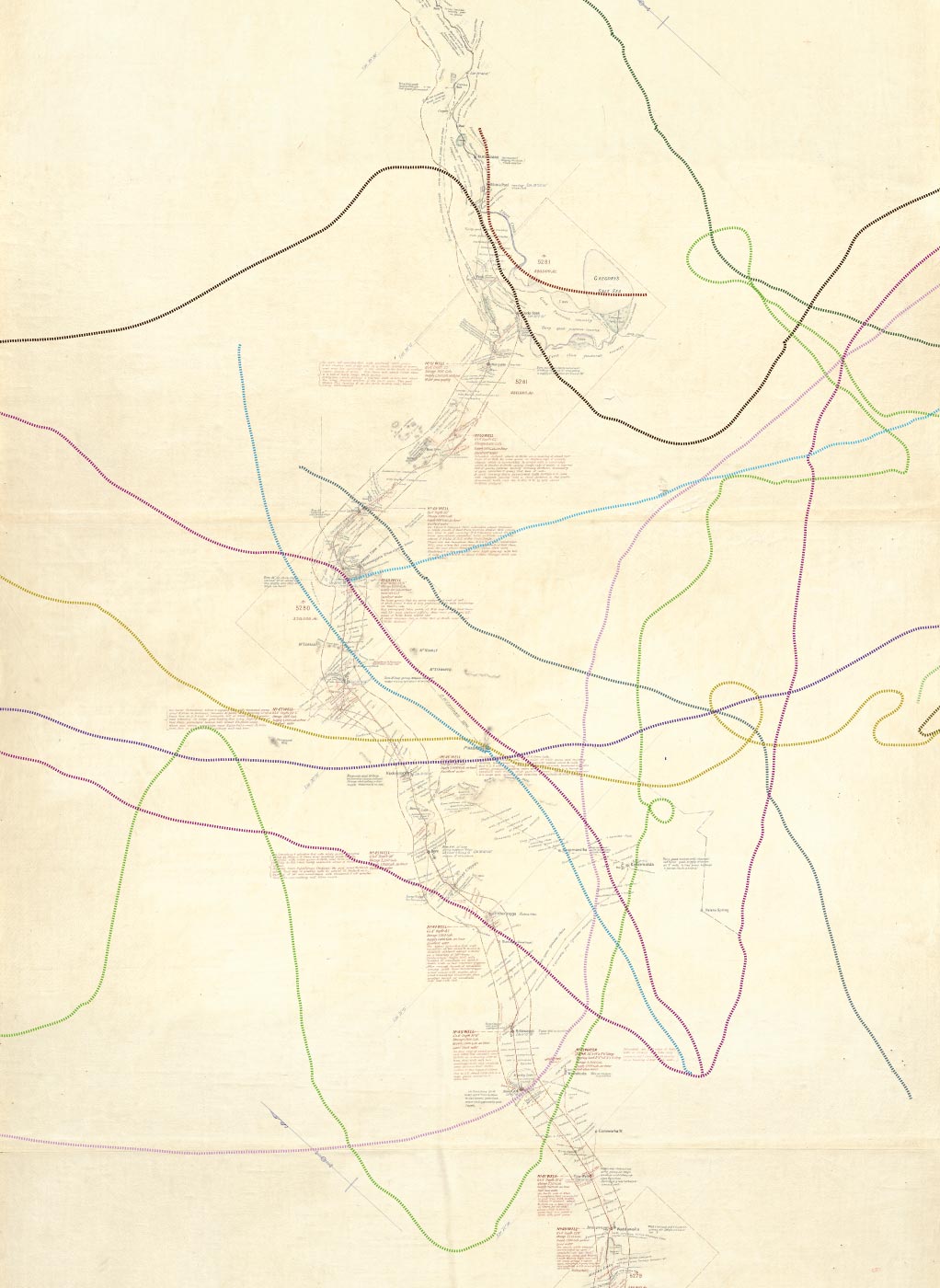

The most obvious thing, of course, is the Dreaming and every exhibition in some way has to address this, but most exhibitions don’t actually explain and most people don’t actually understand what the Dreaming is. We take it for granted as if it is non-problematic. It is commonly assumed that all Western Desert paintings are about the Jukurrpa in the desert, which is the Dreaming: the creation period in Aboriginal cosmology during which ancestral beings moved across the land singing, fighting, loving, killing each other, stealing and having fun. As they travelled they created the features of the land. They also established the moral, practical and spiritual laws that continue to govern Aboriginal societies. These Jukurrpa narratives form an intricate network of ‘dreaming tracks’ or ‘song lines’ that criss-cross the desert country. This is a map that was produced out of the FORM Canning Stock project that led to the Yiwarra Kuju exhibition [image shown]. It shows a small cross-section of the northern Canning Stocking Route. That is Canning’s map underneath. Across it is just a small survey of the dreaming tracks that run across that Country or that pre-existed the line that Canning drew in the sand.

It was the knowledge of these songs that allowed people to navigate their way through the desert – both physically and spiritually – finding water, food and meaning in their desert world. It makes sense that such narratives, such maps, are an integral part of the economic and cultural strategies of desert artists today.

[Image shown]. Patrick Tjungurrayi paints one of the major Dreamings of the desert Country, the Tingari line, which runs parallel to the stock route in the eastern Country. If you imagine this map as – that (left side of the painting) is the southern end of the painting and that (right side) is the northern end, it is actually painting the Country from Well 33 in the south up to Balgo and Billiluna at the northern end of the Canning Stock Route. So it is about half of the Canning Stock Route country. This (bottom section) is the east and the top side of the painting is the west. It is this line, this Dreaming, which Patrick paints predominantly for the art market. The story for it is usually relatively brief because of the restricted nature of the Dreaming. There is then, it would seem, not much for the audience to understand of Patrick’s art other than the fact that it is great art.

But this painting changes that and challenges that. During the research for the FORM Canning Stock Route project, Patrick accompanied this painting, as he was painting it, with a series of oral histories that illuminate his Country and artistry in revelatory ways. The first point to recognise is that he folded this Tingari line (bottom line of white squares), the concentric squares which is classic Tingari iconography, up into the country to show the Canning Stock Route. So this line (top line of white squares) is actually the Canning Stock Route. As he unfolded this line out into the painting, he also unpacked his memory as we were driving through the desert rolling this painting up, unrolling it each day and painting it at different sites along the Canning Stock Route during the project.

The first point that he made about this painting was that, as a young man, he and his brother used to walk about this Tingari country here, that they would walk over to the Stock Route to meet up family and have adventures of their own in the desert. But also that Patrick himself as a young man eventually walked out of this country up to Balgo after his family left from well 40 (which is Natawalu, where the famous story of Helicopter being picked up by the helicopter and being flown up to Balgo … which if any of you have been in the exhibition will know). Patrick was actually there but he was a young man on his law business and he couldn’t travel with the other people in the family, so he had to wait behind and walk up by himself as a young man up out of the desert. He used the wells of the Canning Stock Route to guide him up to Balgo. So it is this life journey embodied in this line.

But laid within that is another kind of history which is Patrick’s knowledge of what happened at these places. Patrick enumerated events that are not in the history books. I am not going to point at the exact right well each time because I can’t count, but at well 37 he told narratives about his family killing a white man there who was prospecting for oil. At well 41 he narrated the story of Peter Goodji’s family. He was a Fitzroy Crossing artist whose family was massacred there for killing a camel, and everyone was killed. Peter Goodji was the only one who got away as a young boy after watching his family massacred (he being hidden beneath Spinifex). At well 45 and well 50 Patrick narrates another series of massacres that are not recorded in the history books.

These conflicts, like so many on Australia’s frontier, are missing from the annals of history because they were not written down. But they are not forgotten. The value of such a painting is not, however, in simply filling the gaps or correcting the facts of Australian history. What is important is the way those events and our history are imagined and remembered through alternative world views to provide a different perspective not only of the past but of what that past continues to mean to desert people today. It also adds an extraordinary dimension to this painted Country that has been hitherto entirely absent from Patrick’s reception and reputation as a fine artist.

As the Dreaming shadows ‘history’ in this painting, this is Country marbled with parallel visions. Through the transference of the iconography of the Tingari concentric squares Patrick absorbs the Canning Stock Route wells into an abiding Aboriginal understanding and vision of the desert. The squares are multivalent themselves: just as they absorb the stock route into the desert they also poetically conflate Patrick’s historical journey along the CSR as a young man with the mythic quests of the Tingari men. Transposing sacred ancestral itineraries with his own, without collapsing the difference, is to me an act of great Australian poetry and artistic significance.

You could argue that Patrick’s painting is unique. Most people don’t paint these great dreaming narratives over vast distances. Most people don’t document multiple historical events in one painting and most people don’t feel authorised to paint this much. However, everyone paints combinations of this kind of content when they paint their Country, because the dreaming is inseparable from the land, from family, from history and the currents of your own life.

While Yiwarra Kuju as a whole presents a vast political tapestry of Dreamings, individual paintings return us to the often overlooked intimacy of desert art. [Image shown]. Milly Kelly’s tiny brown painting, which is maybe my favourite in the whole exhibition. It is rough and rusted and it has a little yellow arc in the corner. This was Milly’s home, the shelter that she lived in as a girl with her family, and it was these homes that colonial history interrupted.

For Aboriginal people the creation of the Canning Stock Route, the sinking of the wells and the coming of the drovers did not happen in time, as we commonly think of it, but in place. Events do not just happen in the desert; they happen here or there, in the Ngurra – or Country – that people paint. Like Milly, most artists paint relatively small areas of Country. In some essence this is just one square in Patrick’s painting. It’s a bit of a neat analogy but that is effectively what it is. Most people paint a relatively small area of Country to which they are intimately associated: their waters, and the events, ancestral and otherwise, that have come to give meaning to those places. It was these waters that the stock route usurped, and these stories that it stumbled into. Sometimes these worlds did not merely overlap, they collided. There are many examples of that in Yiwarra Kuju. And like the bones that Patrick remembers scattered around Well 41, that conflict becomes sediment in the story of that Country – pigment in the colour of its paintings.

As such, you don’t need to paint half the Western Desert like Patrick to exhibit this complexity, and I want to end here with one final painting by Lily Long. [Image shown]. Lily Long’s painting of Tiwa, or well 26 on the Canning Stock Route. It provides a final example of a place where personal, historical and ancestral threads entwine around a single site. ‘This is the Canning Stock Route,’ Lily starts her story, and we are invited to imagine ourselves with Lily as a child perched on the hill watching the drovers come in for the first time, watching 500 head of cattle come and drink at this squared-off well. You can see the rounded soaks that Lily’s family used to drink at and then this squared-off Canning Stock Route well with the Canning Stock Route there. Lily talks about sitting here as a young girl watching the drovers and being terrified and not knowing what the hell these cattle were sitting around in her Country and running away.

Then other parts of the story that she narrates is of these hills here. As she is describing that domestic narrative, she starts to describe the story of an ancestral woman who was trying to kill the Wati Kutjarra, important Dreaming figures in this part of the Country. That woman was trying to poison those two men in the Dreaming and effectively she ended up becoming these hills there. Then Lily in another part of the story for this painting says, ‘Oh and by the way, my uncle was also poisoned by drovers on the Canning Stock Route.’ It’s an extraordinary condensation of these layers of meaning into one completely unified image of a place.

Through one place, Tiwa, these threads of memory, art and Country – History and the Dreaming – are interwoven. In this place-based view of the world presented by artists like Lily Long and Patrick Tjungurrayi, stories from the Jukurrpa, from family, from colonial history and from personal experience are all layered in the sites where they happened, where they continue to happen in contemporary art. Country is a kind of memory. Our engagement with Country, through exhibitions such as Yiwarra Kuju and Yalangbarra – where we are encouraged not simply to look at paintings but to walk around inside the Country they create for us – is crucial to a broader kind of memory, both personal and political, of what it means to even be living in Australia today. [applause]

MIKE PICKERING: I will take the opportunity to remind people the Patrick Tjungurrayi painting is on display in the Yiwarra Kuju: Canning Stock Route exhibition but also if you go and look at it, do go into the theatrette because we have Patrick talking to that painting and describing those stories. Again it’s the stories that bring that painting to life, at least from a museum perspective.

Before I hand over to Howard, I was also intrigued by the idea that we have the map of the Dreaming tracks as recorded in a Western convention. You have the colour which shows the dreaming tracks, then you have places of non-colour, so that may imply to the non-Indigenous people that there are places without dreamings. But in reality it’s how we map the country versus how Aboriginal people have mapped the country, which is the whole country is saturated with those colours. That again comes out in the Patrick Tjungurrayi painting where there is no distinction between here and there; everything merges one into the other. Thank you very much, John.

Now I shall immediately hand over to Professor Howard Morphy to continue the discussion in regard to the north-east.

HOWARD MORPHY: Yalangbara is a place. It’s a very dramatic landscape in eastern Arnhem Land on the Gulf of Carpentaria. You approach it as a huge chain of sand dunes that separate the sea from the inland. It’s also the landing place of the Djang’kawu sisters, two of the great creative ancestors of north-east Arnhem Land, and it’s in the country of the Rirratjingu clan.

I will give some instances of their journey as I go on with this talk. This is a painting by Mawalan Marika that has an important place in the history of Aboriginal art, because it was one of the paintings collected by Tony Tuckson and Stuart Scougall from Yirrkala in 1959. It was one of the first sets of paintings and carvings that breached the walls of an art gallery in Australia. The great collections made by Scougall and Tuckson had pride of place for a while in the forecourt of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. They then took a back seat for a while but they are now again exactly in that place now. Times have changed. What was really challenged at the time when Tuckson and Scougall made this collection – indeed it was said by many of the reviewers that this should not be in an art gallery, this should be in the Australian Museum or some other museum – is no longer the kind of argument that can be put forward. Although as late as the 1980s the Art Gallery of New South Wales was thinking that perhaps these wonderful paintings could have been transferred to a museum. I am sure it’s a great regret to the Australian Museum in some ways that they weren’t transferred to them.

This painting by Mawalan represents the great creative of the Djang’kawus who gave birth to the clans of Yolngu people, and in particular of the Dhuwa moiety. This is an extraordinary painting of this incredible act of birthing where you can see here the male and female children of the Dhuwa moiety clans. The act of birth took place at one of the waterholes that they created. When they landed in eastern Arnhem Land, they had with them a whole series of sacred objects they had brought with them and they had two great digging sticks called Mawalan. They used these great digging sticks to get food but also to get water by digging wells in the ground. Then they helped themselves create food by planting digging sticks around waterhole and they then grew into the trees that surround the waterhole. Then covering themselves with Nganymarra mats, woven mats, they then gave birth to the clans. You will see in the exhibition very much at the centre there is a beautiful woven mat. This signals the fact that in many contexts the category that Yolngu would include as sacred objects or Madayin or manifestations of the ancestral past as well as paintings and painted designs such as this, would include ceremonial digging sticks, dilly bags and apparently mundane functionary mats that could be used to shade people from the heat of the sun or in this particular context to provide modesty in giving birth.

The Yalangbara exhibition was the idea of Dr B Marika AO who then collaborated with Margie West of the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory. Dr B Marika AO was the daughter of Mawalan. [image shown] This is a section of the painting we have just seen, but it’s actually Mawalan painting himself looking at one of the great digging stick sacred objects that is named after him. Dr B Marika AO was Mawalan’s youngest child. Dr B Marika AO went on a quest to discover all of the paintings and objects that the Rirratjingu clan and related clans had made over a period since European intensive colonisation, which in north-east Arnhem Land was in 1935 with the founding of the mission station at Yirrkala.

From the very beginning Yolngu were producing paintings, paintings for sale to Europeans but paintings also to persuade Europeans of the value of their culture and as an educational resource. Those paintings, objects, photographs, sound recordings and films became distributed in museums around Australia. Dr B Marika AO thought it would be wonderful if she and her nephew Mawalan, named after his grandfather, went and documented all of these and brought them back in images to Yirrkala. At the same time they were making Yalangbara as a place part of the national estate, something that they thought was fundamentally important not only to Yolngu but to Australia.

When Dr B Marika AO was first involved in this project she didn’t think an exhibition was necessarily going to be the outcome, although it could be an outcome. She thought that a book could be an outcome, and a book was the thing that was produced first. In the beginning of this book Yalangbara: art of the Djang’kawu she said what she was trying to do through going around and bringing all of these things together was to create something that was like that film Ian Dunlop made In memory of Mawalan. This is one of the interesting things that then poses: in what sense did Dr B Marika AO see the book and see the exhibition that we will be able to see later as like Ian Dunlop’s film In memory of Mawalan? In what sense is an exhibition or a collection of paintings like a film?

The film was a film of a memorial ceremony – I hope that they will be able to screen it in the Museum – in memory of her father that re-enacted the great events of the Djang’kawu’s lives in Yolngu ceremonial performance. In a way the reason it is the same is that these paintings, these objects as well as the songs and dances associated with them are all manifestations and evidences of the ancestral past. They are all in Yolngu terms seen in the context of action in different places, in different times that Yolngu themselves can bring together for particular purposes, whether it’s a circumcision ceremony, a burial ceremony or a memorial ceremony. When Yolngu think of these things, they look at them in terms of the past, present and future – and in the past, though that past is an ancestral past that is here in the present and will be there in the future.

This is one of the sacred dilly bags that the Djang’kawu sisters hung on a tree [images shown]. This is a crayon drawing produced for the anthropologist Ronald Berndt by Mawalan, which shows the journey of the Djang’kawu sisters from Buralku, the land of the morning star, over in the sea to the east beyond Papua New Guinea in some imaginary distant country. This is the journey that they took to these great sand dunes of Yalangbara that you see at the top [image shown]. The representation of this journey that happened in the past is made up of a whole series of separate paintings that represent different named places on the way, different named places in the sea: places where they saw a group of ducks flying from the surface of the sea as they approached the land; an area where there were flying foxes suspended in the trees on the shore that they heard; a place where they saw a goanna in the sand dunes; a place where they got sunburnt by the heat of the sun; and a place again where they saw goannas playing in the sand. These are all paintings which mark places on the journey, and each of those is associated with songs, with dances and with sacred objects. One of the things that these paintings, the sacred dilly bags and the digging sticks represent or are manifestations of is this ancestral dimension that underlies the present, that gave birth to the clans and that is the possibility of renewing the presence of the ancestors today and into the future.

In the context of performances today, they are re-enactments of the Djang’kawu sisters. I am going to show a very interesting performance because this is the first Yalangbara exhibition opening in our understanding of that word. This though is a performance in the Administrator’s house in Darwin in the Northern Territory where they launched the book that preceded the exhibition by a year, a book that hoped that an exhibition would come, a book that was also associated with a conference in which many of the Rirritjingu clan were present, talking and communicating about the Djang’kawu. This performance was to open that particular event. It was a dance performance that is very similar to the dance performance that yesterday the Rirratjingu were able to open this exhibition. [image shown] Here you can see women dancing the ancestral Djang’kawu.

This is the digging stick I was talking about, the Mawalan, that object that the artist Mawalan was looking at when he painted himself reflecting on his identity in relation to his country and in relation to Yalangbara.

[Image shown] Here is his namesake, Mawalan 2, a great Yolngu artist of today, who was one of the leading dancers yesterday when the exhibition was opened. Sadly they all had to return today. I was hoping that people would have been able to stay on, but in terms of the planes and schedules they have gone back.

[Image shown] Here are Yolngu women re-enacting the process of the Djang’kawu sisters giving birth, moving their digging sticks into the ground, creating the well around which the children were born. You can see in the exhibition how important it was that Yolngu performed at the opening ceremony. Yolngu don’t perform at an opening ceremony simply because they wish for a public spectacle. Yolngu are very conscious that their dance forms are very persuasive, but if an exhibition doesn’t open with a performance that relates to its significance and meaning, it is seen by Yolngu to be very much impoverished. So in a way the dance performance puts all of these objects into action and places them into a different space and time.

Finally, these paintings are very much part of the future. [image shown] This is a painting associated with the Djang’kawu sisters that is being done on a boy’s chest in a Yolngu circumcision ceremony two years ago, because the initiates are incorporated into this ancestral dimension through ceremonial performance. The aesthetics of Yolngu art is part of the creation, the endowment of ancestral power and the transformation or transfer of that power from one generation to the next.

Yolngu as a system is a system in action. It’s a system that is able to be adapted to very different kinds of circumstances. It was remarkable: the ceremony at the Administrator’s house in Darwin was actually supposed to take place outside in a very large garden. There was this most colossal thunderstorm that happened just at the moment it was supposed to be opened and everybody moved immediately inside and the ceremony took part in the verandahs that surround the house. For yesterday’s ceremony Yolngu arrive with no rehearsals and while in a sense rehearsing by doing some preliminary songs were able to create a performance that led people around and into the exhibition as a whole, but the individual art works themselves are part of a process of dynamic continuity, education in art but also tremendous innovations.

[images shown] This is one of the first paintings collected from north-east Arnhem Land, a painting by Mawalan of the sand dunes at Yalangbara. This is a print made by Dr B Marika AO of exactly that same place reflecting the fact that it’s on one side of the sand dunes rather than the other, a side that is associated with the sunset rather than the sunrise. If we had more time we would be able to see strong similarities, but I will just point out the fact that this is made of intersecting cross-cutting parallel lines which are a sign of Yalangbara as a place.

Finally this is a painting by Wanyubi Marika that is in the exhibition, I think, or a very similar one if not this very one. This is a painting of their long journey from the land of the morning star, to Yalangbara. What they did was they followed the light of the morning star. They paddled their canoe. Many of the songs evoke the sound of the canoe being paddled through those waters – sounds such as ‘mumuthun’ [makes noises] as the paddles go one after the other. This is the impact of the paddle in the water lit by the light of the morning star as the paddle goes in. As the water in this case relatively still is fractured by the effect of the paddle, it ripples out and gradually goes back to the smooth water of the incoming gentle tide.

Here you can see Yolngu art is used to create aesthetic effects that can translate cross-culturally un-problematically but in a sense need that guidance to go with them that Yolngu have always sent with their paintings. They send it in the form of their own dances which, if people follow the movements, can begin to get ideas about what it is but also in the documentation that goes with their paintings. Yolngu do not see the meaning of art or its cultural significance in any way separated from its aesthetic power. I suppose that goes some way towards answering Mike’s question in a way that has much in common with John’s answer. I will finish at that point, thanks. [applause]

MIKE PICKERING: Thank you, Howard. Howard brings it to the fore so that you can appreciate the difficulty in a museum of trying to convey and condense that complexity of culture through art or through any object into an exhibition. An exhibition is simply the tip of the iceberg. It’s a real challenge to not only conveying the message but also conveying the enthusiasm and life. In both cases with Yiwarra Kuju and with Yalangbara we were remarkable privileged to have a number of the artists or families of the artists – people who were authorised to talk to those works and to sing to those works – present at the openings. In doing their ceremony, although many people couldn’t be there, they seem to leave a vitality in the exhibition that persists long after they have left. We hope that we can continue doing that in the future. This also makes sure that the voice that you hear when you come to our exhibitions is the voice of the artists, the voices of the culture that has produced those works first and foremost.

We will move now on to questions and comments. Let’s have a bit of controversy here. We have roving microphones because it is being recorded. As the microphones come around you are welcome to identify yourself if you wish; if you prefer to remain anonymous that is fine too. We want to get as many views across the audience as possible so don’t persist in long comments if you can help it.

SPEAKER: I wanted to follow up with John on his point that we are not able to understand the art in the way that artists might wish. Do you think this is something peculiar to Indigenous art or is it a fact of life of all art and it is just that the distance between what the artist might intend and what the viewer might receive is greater perhaps in Indigenous art?

JOHN CARTY: I definitely think that is part of it but I also think that, if you want to understand Jackson Pollock, you go and read 18 books, you go and read The Shock of the New, you go and read catalogues and you educate yourself about modern art. You have a commonality with that cultural tradition in the West but you go and learn about art so you understand what that extraordinary painting is about.

There is a disjunct in Australia where we assert that the way to respect Aboriginal art is just to acknowledge it as great art when I think the art history that is required to appreciate these paintings actually involves a lot of what people pejoratively call anthropology – it shouldn’t be anthropology; it is just about educating yourself and learning about what the artist is painting, which is all of these things that we are talking about. It is to learn about Country, to learn about Aboriginal understandings of family and of the Dreaming, and not take those concepts for granted, as you wouldn’t take cubism for granted. You go and learn what cubism is. I think it is about the way we frame Aboriginal art. In many ways we try to give it equality and say it’s great art but in art historically we haven’t actually treated it with the same respect. That is the main point I would make about that.

PETER THORLEY: Peter Thorley from the National Museum. John, you said these paintings – Howard might like to comment on this as well – are mostly about Country. Would you feel comfortable describing them as landscapes?

JOHN CARTY: Howard would probably, more so than I. I think it depends on what you understand as landscape. The idea of landscape is not what I am talking about with these paintings. I think all of this cosmology, mythology and western perspectives on the universe are encoded in Western landscapes so they are not naked artistic practices. So in some ways the relationship between landscape and Aboriginal paintings of Country is more nuanced and more interesting. But I guess my answer at the moment, and that might change over time, is that I actually think these paintings of Country are closer to what we understand as paintings of portraiture, as objectifications of the self through the medium of the land of which you are a part. In the pendulum of landscape and portraiture I think Aboriginal art from the desert at least – in my understanding of it – is closer to this notion of portraiture and self-portraiture through land. But Howard will disagree.

HOWARD MORPHY: Howard certainly wouldn’t call them landscapes unless you call Sidney Nolan’s Kelly series landscape or something like that. The whole point is that landscape refers to a particular genre of painting where the focus was actually on land in association with a particular view that developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in relation to how one would portray that. It is a word that is quite difficult to apply to most complex art forms. I probably wouldn’t call it portraiture either but I can see very strongly there are elements of portraiture in some of those paintings, almost literally in the case of Mawalan painting himself, which gives a real clue to the sense in which Yolngu do see these as part of their identity and an identity they connect into the future.

It is very important to recognise the enormous diversity in Aboriginal art both within the same sort of cultural traditions such as Yolngu but also between. If we were giving lectures on that other great collection that was made by Scougall of Tiwi Pukumani poles, we would find it very difficult to talk about it in the terms that we have been talking about these paintings here. There are actually great similarities between Yolngu artistic tradition and that of the peoples of the Western Desert, even though the iconography and all sorts of techniques are very different. But in the case of Pukumani poles, people have tried to force Pukumani poles into representing ancestral beings in a particular place on a particular journey and so on and so forth. But really that is not how they were and are seen, understood and commissioned by Tiwi for their own ceremonies. There is much more emphasis on aspects of the expressive dimension of those poles in relation to ideas of persons, mourning, loss and the vibrancy of life – a whole series of things that are actually more metaphysical. Those metaphysical things exist in Yolngu paintings as well, but there isn’t that kind of narrative associated with the art of Tiwi that there would be in north-east Arnhem Land. So I think we have to recognise this incredible rich diversity.

MIKE PICKERING: I will exercise the MC’s prerogative and just interrupt at this point to say that I believe they are both landscapes and portraiture, remembering of course that my publications in Indigenous art constitute a 500-word article about a message stick. The reason is landscapes are all culturally constructed; they are not synonymous with environment. You are not seeing what is actually there. The artist situates themselves to reproduce something that captures the values they want to see represented through that landscape. I will see here, I can’t see the valley, I am going to move to the left. If you move to the left and get out from behind the tree, you can see the valley. All landscapes are culturally constructed by the values of the artist or the artist’s culture.

In terms of portraiture, I remember a discussion we had with the Portrait Gallery was how could they represent Aboriginal culture through the Portrait Gallery when they didn’t have that many portraits of Aboriginal people. We had a discussion about how a portrait, a head and shoulders, will tell what you a person looks like, but these sorts of art works will tell you how a person feels that they are. This is what I look like but this is who I am, and that is expressed through the spirituality. They are not exclusive, of course; it’s not an either/or situation, there are multiple levels of interpretation. Now I can run off to the question and I don’t have to respond to any anyone on that question.

QUESTION: I very much agree with the notion that all art, whether it’s Western or Aboriginal, has culture built into it. I was always intrigued by looking at Glover’s early paintings of Australia which brought his English culture to it and it doesn’t look very much like what we now understand as Australian painting towards the end of the century.

When I went to the National Gallery of Australia extension of the Aboriginal paintings I was absolutely knocked out by it – and I was knocked out by the quality of it in art terms. Allowing and to some extent understanding the arguments between anthropology and art, how do you judge the quality of a painting in terms of good and bad artistically, because my favourite painter Emily Kame Kngwarreye – when she was here, she absolutely knocked me out artistically.

HOWARD MORPHY: I don’t really think there is any difference between eventually making assessments of quality with Aboriginal art, Papua New Guinea art, Byzantine art or contemporary Australian art. What one actually has to do is have both a body of knowledge and criteria for making judgements. That is an extremely complex thing to do when one is looking at things across place, time and culture.

The reason I can say this with a degree of confidence is that, in the Yolngu case, the kinds of judgements that Yolngu make about quality are analogous to the kinds of judgements that in the end once non-Aboriginal people and European people in particular start to appreciate the art of north-east Arnhem Land are going to map on to quite a considerable extent. Initially, if you looking at art that you are completely unfamiliar with, you won’t have any basis or means of making judgements. When there are new movements in Western art, it’s the classic time when 90 per cent of people will say ‘This is rubbish. My children could do better. This is crazy. An ape could do it.’ And then after a period of time when a degree of knowledge and appreciation has developed and when people begin to develop criteria of judgement that relates to that particular art style, then people will be starting to make informed judgements that are about things that are quite qualitative.

The kind of artists who Yolngu will argue, ‘Please do the painting on my son’s chest in his circumcision ceremony’ are the ones that in the market context most art galleries will say, ‘This is a painter who is producing paintings of quality’ – but just like in any art practice there are works that people produce that are not their best, and they will often acknowledge that is not their best. I can give one comment from Narritjin Maymurru, who is an artist whose biography I have been writing for about the last 20 years – if I ever have time I will finish it. He was talking about his own paintings and when they were finished and he said, ‘I can sit here and I can work on this painting for two or three days. I am painting it and I’m not sure, it looks a mess. I can’t work it out. But then suddenly it all comes together.’ Those are the kinds of ways of talking about an art work ironically – or maybe not even ironically – that can resonate across artists across cultures.

JOHN CARTY: It is always difficult coming after Howard. I don’t have a great deal to add to that. In terms of a concrete example, one of the things that we did in the Canning Stock Route exhibition is that we didn’t exclude paintings just because they weren’t the best paintings. We wanted it to be a big, sexy, fabulous, persuasive, visceral experience so that you walk in and, as you were saying, you are blown away by the quality of these things pulsing on the walls. But that wasn’t the only criteria. There are paintings in there that aren’t the best work by that artist but they are an integral part of understanding that story and that Country. So those paintings are in there because of their meaning, the artistic intent, and the way that that hangs together in an experience of that Country. I would perhaps cheekily suggest that, after you have been blown away in the NGA by all these pretty pictures, you should come over to the NMA and learn about what they are about by going through the Canning Stock Route exhibition. That was a bit cheeky. I like the paintings over there.

MIKE PICKERING: That was very cheeky. We are just on 1.30 and so I will formally close proceedings because that means I can say I held to time. We can continue the discussion afterwards. While all this discussion is fresh in your mind, do rush off to the exhibitions while you are here and basically do what I am going to do and apply it. As I say, there is so much information out there and so much we need to know. What we are finding here in the Museum is that our audiences are coming in and really engaging with that extra content. People aren’t coming in just to look at nice art works, they are coming in to engage with those stories, and it is those stories first and foremost that enrich the entire exhibition.

HOWARD MORPHY: On the other hand, if you look at the Yalangbara exhibition, the majority of these paintings are paintings that are in the Art Gallery of New South Wales. They are exhibited here in the space at the Museum in a way that they can be appreciated better as art than in the crowded spaces in the Art Gallery of New South Wales where they usually are. I think that kind of opposition between an art gallery context and a museum context is one of the things that needs to be challenged at the present time. We need special spaces for viewing art and for viewing beautiful fine objects in a way that enables one to fully engage with them, but at the same time I think all art needs and deserves to be contextualised in other contexts. So I think this opposition is one that we want to get away from.

MIKE PICKERING: I will again interrupt and say I agree. We are having this lovely little fight going on, this little tension, but one of the problems is that people from an art gallery will go and visit a museum and say, ‘This is wrong, it’s too much this,’ and people from a museum will go to an art gallery and say, ‘That’s wrong, there is not enough of this or something else.’ The thing is they are just alternative ways of looking – each is equal – we need to probably have a look for other even more alternative ways of presenting and viewing these works in order to really appreciate them.

By the way, for the Yiwarra Kuju exhibition the current visitation numbers stand around 75,000 mark. It is on its way to being the most popular exhibition that the Museum has held in its ten years, so we are feeling rather pleased with that. I hope you will join me in thanking our speakers. [applause]

Disclaimer and copyright notice

This is an edited transcript typed from an audio recording.

The National Museum of Australia cannot guarantee its complete accuracy. Some older pages on the Museum website contain images and terms now considered outdated and inappropriate. They are a reflection of the time when the material was created and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Museum.

© National Museum of Australia 2007–25. This transcript is copyright and is intended for your general use and information. You may download, display, print and reproduce it in unaltered form only for your personal, non-commercial use or for use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) all other rights are reserved.

Date published: 01 January 2018