The Not Just Ned exhibition developed by the National Museum of Australia features personal objects and stories from some of the thousands of Irish people whose stories have become legends, or whose efforts have made Australia what it is today.

Learn more here about convict squatter Ned Ryan, controversial grazier Isabella Mary Kelly, dancer Lola Montez, copper magnate Charles Bagot and would-be political assassin Henry O’Farrell.

King of Galong Castle

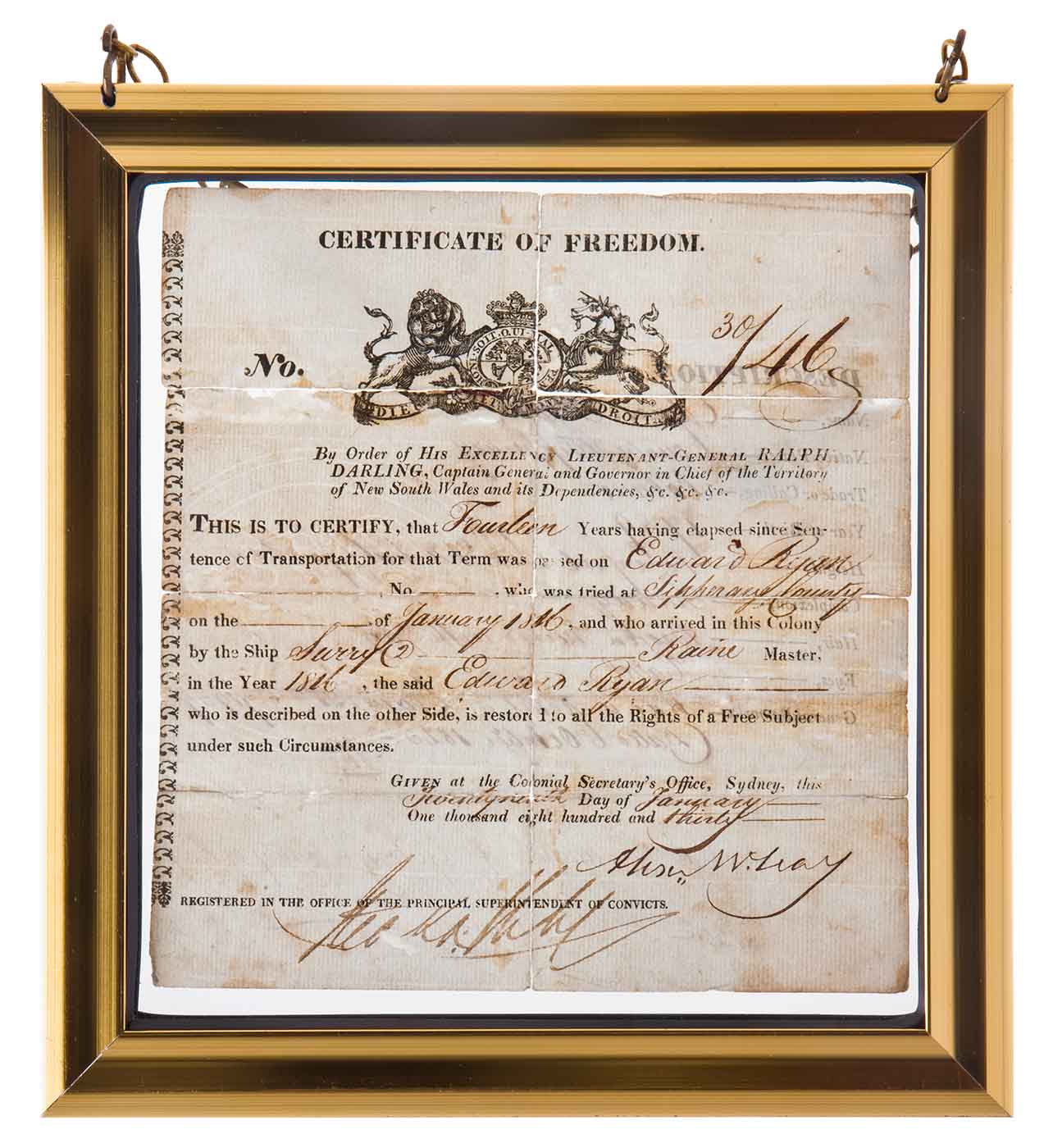

What did ex-convicts in early colonial New South Wales carry with them to prove they had served out their sentences of transportation?

Edward ‘Ned’ Ryan, of Galong, New South Wales, always kept about him a small red wallet, which held his folded-up ‘certificate of freedom’. Ryan received this vital document in 1830, the piece of paper indicating that he was now a free man and should be treated as such.

We can learn a lot about Ryan from the two sides of the certificate, which also bears his signature. He was born in County Tipperary, Ireland, in 1789; he stood ‘five feet six and a half inches’ (1.7 metres) high; he had a ruddy complexion, hazel eyes and ‘brown hair mixed with grey’.

Ryan had been part of a group of men who had torn down a dispensary in his native parish of Clonoulty, when they realised that British soldiers were to be stationed there. Transported for this crime in 1816, along with 12 others, he left behind a wife and two children.

They joined him in New South Wales 32 years later, by which time he had become a wealthy man, referred to politely as Mr Edward Ryan Esq. Indeed, so extensive were his pastoral leases that he was sometimes called ‘The Patriarch of the Lachlan’. His house, with a castle-like tower, was known locally as ‘Galong Castle’.

The wild woman of the Manning Valley

The stories that have circulated about Irishwoman Isabella Mary Kelly are amazingly lurid. As recently as the 1970s and 1980s tabloid articles about her feature headlines such as ‘Female settler was tyrant to assigned lags’, ‘Wild ways of grazier Bella’, ‘Sex-hungry tyrant lived by law of the lash’ and ‘Isabella Kelly — a bitter, sadistic hellcat of a woman’.

The accompanying stories are little short of libellous to her memory, one even accusing her of flogging men to within an inch of their lives for refusing her favours. Most of these accounts end with Kelly receiving her just deserts by dying as an impoverished beggar living in a cellar in Sydney’s dockland in the 1890s.

The truth is less spectacular. Kelly came to New South Wales in the early 1830s and acquired land in the Manning River district. She successfully managed her property herself, becoming a noted breeder of horses. Current thinking about Kelly is that she was greatly resented for the free lifestyle she led as an unmarried woman.

In 1859 Kelly was imprisoned for perjury on the false evidence of a neighbour. Although soon released and pardoned, she never recovered physically or financially. After a number of Select Committees of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly had examined her case, she was awarded the inadequate sum of £1000 compensation.

She died in Sydney in 1872, not wealthy but certainly not a beggar. Kelly is now recognised in the Manning River area as a pioneer woman of great determination and ability.

The Spider Dancer

Of all the entertainers attracted to the Australian colonies during the gold rush of the 1850s, none left behind a reputation as amazing as Irishwoman Elizabeth Rosanna Gilbert, better known as Lola Montez.

Montez spent just 10 months in Australia — between August 1855 and May 1856, performing on the Victorian goldfields and in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide.

The miners loved her, reputedly throwing gold nuggets onto the stage to show their appreciation. But the Sydney Morning Herald described her dancing as ‘the most libertinish and indelicate performance that could be given on a public stage’. So what was all the fuss about?

Montez’s most famous performance, and the one which pulled in the crowds, was the ‘Spider Dance’. As she swayed on the stage of the Royal Victoria Theatre in Adelaide in December 1855, her act was captured on paper by artist John Michael Skipper.

It began with Montez pretending to have become entangled in a spider’s web. She then discovered one spider after another, revealing her petticoats as she tried to shake them loose, all the while dancing with abandon and passion until all the creatures had been shaken out onto the floor, where she excitedly stamped them to death.

Audiences were ‘held spellbound and somewhat horror struck’, but when she had finished the applause was ‘thunderous’.

Copper at Kapunda

Charles Harvey Bagot came to South Australia from Ireland in 1840, aged 52. His aim was to acquire land in the colony and settle on it as a gentleman pastoralist. However, wool prices were low in the early 1840s, and Bagot must have wondered whether his emigration relatively late in life had been worth it.

One day, on his property at Koonunga, 100 kilometres north-east of Adelaide, Bagot’s son, Charles, picked up a piece of rock, which turned out to be copper. The ore proved to be high-grade, and the Bagot family fortune — and that of the town of Kapunda — was made.

After Bagot’s retirement as manager of the Kapunda Copper Mine in the late 1850s, the Kapunda miners and other locals were determined to honour the man who had brought so much prosperity and prominence to their town. They commissioned German-born silversmith Charles Edward Firnhaber to produce a handsome cup to be presented to Bagot.

Firnhaber was obliged to use a conventional imported cup for the base, but fashioned for the lid a carved model of the Kapunda mine’s above-ground machinery. On 14 November 1859 hundreds crowded into the town to see the presentation. It was reported that ‘the honourable gentleman was apparently so moved that his reply was scarcely audible’.

Assassination attempt

Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, was Australia’s first royal visitor. On 12 March 1868, at a charity picnic at Clontarf in Sydney, Henry James O’Farrell approached the duke and shot him. The wounded duke was brought to Government House, where the drawing room was converted into a makeshift operating theatre. A specially fashioned golden probe was used to remove the bullet from his back.

O’Farrell’s bullet ‘entered half an inch to right of spinous process of vertebrae on a line with ninth rib, burrowing deeply into the tissues’. Whisked away to a makeshift hospital in the front drawing room of Government House, the Duke was required to remain quiet for two days.

During that time a special golden probe was fashioned to enable Royal Naval surgeons to safely remove the bullet. Later, Queen Victoria showed her gratitude by presenting gold replicas of the bullet to the surgeons.

O’Farrell, originally from Dublin, was tried within the month, sentenced to death and executed. He first claimed he was a Fenian; later he said he had acted alone.

The incident increased tension between Irish Catholics and other colonists, although most of the former would have condemned O’Farrell.

Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital was named as a memorial to the Duke’s safe recovery.

In Irish history Clontarf is famous as the name of High King Brian Boru’s victory, on Good Friday 1014, over the armies of his Irish enemies, who were in league with Viking mercenaries. Boru, who had been trying to bring unity to various warring families and protect the country from the Viking threat, was killed in the battle.

The Sydney harbourside suburb of Clontarf is undoubtedly named after the Dublin suburb that now sits on the site of the ancient battle.