Liz Marsden, National Museum of Australia, 27 March 2009

PETER STANLEY: Can I now introduce Liz Marsden, who’s the Collections Manager at the Victoria Police Museum. She’ll talk about the challenges in collecting and displaying crime. Thanks Liz.

LIZ MARSDEN: Good afternoon. My name’s Liz Marsden. I’d like to start my discussion today with a photograph.

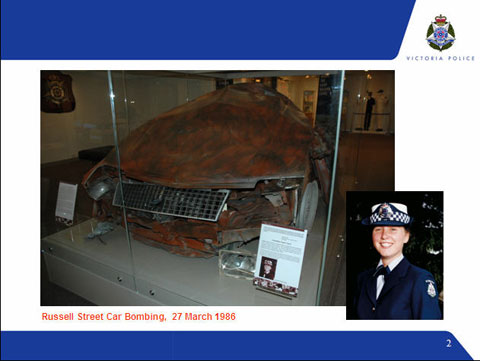

On this day in 1986 at one o’clock in the afternoon a bomb was detonated outside of the Russell Street police headquarters in Melbourne. It consisted of 50 to 60 sticks of dynamite hidden inside the boot of a 1979 Holden Commodore. And it was timed specifically to go off when the most amount of people would be on the street.

The explosion shot shrapnel over two city blocks and caused massive amounts of damage to the police headquarters and surrounding buildings, with an estimated cost of over A$1 million. It injured 22 people, including 11 police officers, and ultimately led to the death of Angela Taylor. She was a 21-year-old police constable, and made her the first Australian policewoman killed in the line of duty.

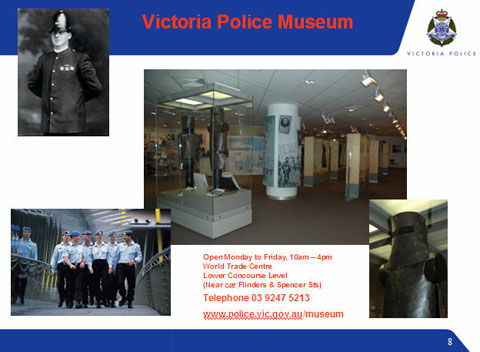

The people responsible for this had no other reason to do this than a pathological hatred for police. [Image shown] This image shows the display - well, the remains of that car as it is displayed in the museum.

The Victoria Police Museum houses three broad collection areas, including the police archives and general policing equipment. The final collections area and the subject of my talk today is that of the Crime Collection, some of which the museum has chosen to display. These objects were originally collected as evidence. It is only when they have served their purpose and the criminals have been caught that they might gradually find their way to the museum collection. I say ‘gradually’ because, as you might imagine, many of the detectives feel a certain ownership over these objects, in a sense, of a job well done. They can add up to many hundreds of hours collecting, analysing, and all for this ultimate goal of gaining justice for the community or for the individuals who have been victimised.

Many of these objects also have very long lives as teaching aids in the detective training school and, indeed, it’s very difficult for the museum to gain these objects, just because the relevant departments often feel so much reluctance to let them go, even if it is to their own museum. Murder weapons, graphic photographs, human skin remains as well as the crumpled shell of the Russell Street car bomb all form an important part of the museum’s collections. Emphasis on displayed objects, however, is placed on the stories these objects can tell through the context of human experience - from the victims, from the police who collected those objects, to sometimes broader consequences of political consequences of those events.

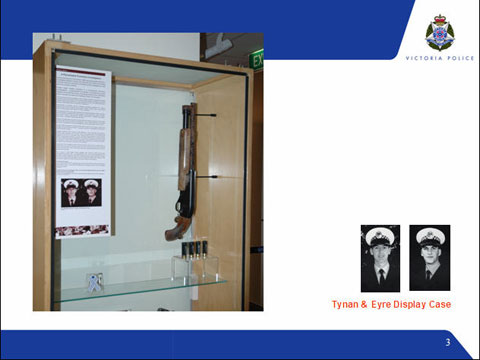

This image looks at the museum’s display of a 1988 murder of two young police constables, Tynan and Eyre. This case was a sort of execution-style murder by the Melbourne underworld. And the Ty-Eyre Task Force which was created was one of the most expansive, longest running investigations of its time, spanning over 895 days.

This photograph shows a sawn-off shotgun, how it is displayed in the museum alongside the photos of Tynan and Eyre, four spent cartridges and the chequered blue and white ribbon. It also demonstrates the museum’s effort to try and display these objects in a clearly defined context. It is intentionally circular in design, leading the eye lastly back to the chequered blue and white ribbon, thereby showing the audience that even from this great tragedy something positive was created.

To date the Blue Ribbon Foundation has allocated more than $5 million to community projects in Victoria, and was also instrumental in helping to establish the National Police Remembrance Day.

How the murder weapon is displayed is also significantly different to how other police firearms are displayed. As you know, and this is something we replicate with other such objects throughout the museum, this murder weapon is displayed in a vertical position, facing upwards, more like a tombstone or a memorial, while the police-issued firearm is presented in more traditional format.

Before the museum re-opened we did question ourselves if we could ethically show such objects. But the fact is, however, it is a police museum, and we have to remain relevant to that group of stakeholders to accurately display their history and their work. The fact is police deal with a lot of issues that most of us generally would never want to experience - ever. And it is just essential that we deal with this, at least for them.

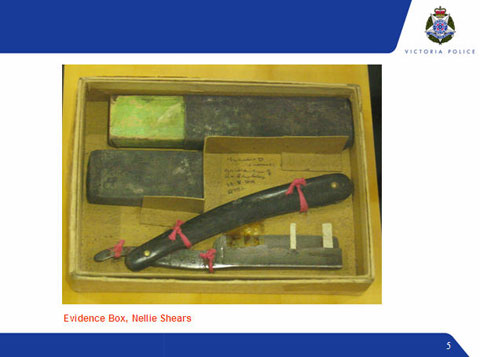

Also these forensic objects can also demonstrate changes in the field over the decades. For example, this image is of a 1930s murder case. It shows the murder weapon. This is in an exhibit box, if I didn’t say that. But this shows the murder weapon mounted in a recycled cigar box. The murder weapon is mounted with sticky tape and string. As crude as this is, this is the beginnings of forensic policing in Victoria. This is a very significant case.

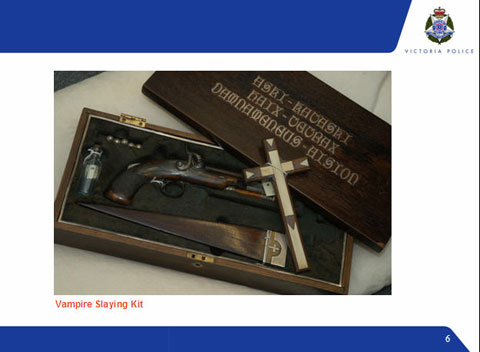

We have intentionally only included objects that can tell a story within our museum from within the thematic displays, no matter how rare or interesting they might be. For example, the collection holds an 18th century vampire slaying kit. It was confiscated during a 1994 drug raid, and comes complete with wooden stake, crucifix, silver bullets, all for your vampire eradication needs. And although it was a popular exhibit in our old museum, it simply did not fit in with any of our current thematic displays. And without a proper context it would have only been exhibited as a curiosity.

Other objects cannot be displayed for freedom of information reasons. These include many crime scene photographs, evidence and inquest briefs. These sort of objects often contain information we’re just not permitted to circulate. When this type of object is registered into our collection it is actually clearly noted in the database that it can only be accessed with permission of the museum manager. The need for good museum practice is also heightened by the fact that these sort of objects can be recalled at any moment if these criminal cases are re-opened, in light of new evidence or new techniques, which makes my job a little bit stressful sometimes.

Other objects cannot be displayed in the interests of public safety. [Image not able to be shown] For example, this is actually a replica bomb created by the bomb squad when they were investigating the Russell Street car bombing. It’s registered into our collection, even though it’s pretty much on permanent loan to the bomb squad. The fact is, we’ll never be allowed to display this. But, registered into our collection it means that if there is ever a change of management in that department it has to come back to us, even if it’s just for storage. It’s obvious why we can’t display it. All the components that make up this object are very easily obtainable. And I actually had to get permission from the bomb squad to show you all. So please don’t go making a bomb or I’ll get into lots of trouble.

Stakeholders are an important factor to consider in any museum. Our difficulty has been to create displays which are both interesting to the police without being too graphic for the general public. With this in mind a lot of attention has been placed on visitor preparation, as there are still many people alive who feel a direct connection with many of the more tragic events we display. For this reason a sensitive balance must be created between respect for loss of life while relaying the historical events and the consequences, and visitor experience must be managed.

In our case a warning is positioned by the entrance informing people of the type of material they’re going to see. The graphic nature of some of the objects was actually taken into account in regard to layout with the more graphic things placed towards the rear of the museum. In that position too it means that if there are any school groups that come in we redirect them away from certain areas. We can close those areas off as well.

School activity sheets are also sent out prior to visits and include extensive discussion points from which teachers can draw from. We encourage students, however, to consider the perspectives from the victims of crime rather than focusing on the criminals themselves. Although they are discussed we try not to make them the focus, preferring to explore what their actions really meant and to the police and the people affected.

Since the museum opened it has dealt with two visitors visibly affected by what they’ve seen. On one occasion we had a gentleman come in who actually worked across the road from the Russell Street complex on the day of the bombing. He heard the bomb go off, obviously. But he also heard Angela Taylor’s cries for help, and he went out to her and he covered her up. He took off his jacket and covered her. The force of the bomb had actually left her pretty much naked. She was in and out of consciousness.

This man, when he came into the museum, admitted that he had never spoken about his experience ever. But he told us how he felt really guilty about not doing enough, about his anger at the ambulances for not coming quick enough. And he feels that if everything had moved a bit faster maybe she might have survived - if you can imagine walking around for 20 years with those feelings. That day he came into the museum we were able to explain to him, firstly, the extent of her injuries, how she wasn’t going to survive, and also why the ambulances couldn’t come fast enough. They have to follow a certain protocol as well. It just reinforced the fact that what he did was probably one of the most heroic and humane acts that day, staying with a woman so badly injured and dying.

When he left both he and his wife - actually his wife said that finally they had a bit of closure, which is nice. We were able to also direct them to counselling services we have within our complex, which is a nice thing as well.

American Museum author Elaine Heumann says:

Museums are safe places for the exploration of unsafe ideas. Places where themes of violence, fatality, grief, suffering and heroism can be explored. Consequently museums can become places of memory and healing and sometimes can incite action. This can only happen, however, if museums continue to tackle these difficult issues in history and tell stories we wish had never happened in the first place.

This is ultimately what the Victoria Police Museum is trying to achieve.

As I’ve shown you today, the importance placed on context within the Victoria Police Museum’s display has helped maintain a human element to which the audience can relate to, like how would I feel if this happened to me, how would I act, that sort of thing. Crime collection objects and murder weapons are, by nature, emotionally charged, since there are almost always victims. Given in a context, however, we are able to explore these events from the perspective of the advances and achievements made by members of the Victoria Police Force and by promoting acts of heroism and courage where due, we can also promote the stories of the police who face unknown dangers every day. Thank you.

QUESTION: by Kate Brennand. You have your collections from the police department. Do you ever feel the need or be forced to be compelled to talk to the victim’s families? Because some material, I’m sure, people will be distressed to find that it’s gone into a museum and their grief has not been resolved. I was just wondering how do you deal with that issue?

LIZ MARSDEN: Well, actually when the museum first re-opened we were ultimately prepared to just take things off if the response was going to be bad. We’re lucky that we’re situated within the Victoria Police Centre, so we have counselling services at hand and things like that. We do include in the textual labels - you will notice on the Walsh Street image that the text label is huge. We’re looking at reducing those, obviously, but in those labels we also have people’s accounts of what happened as well.

At the beginning of this week I had a guy come in from England. He had come from England to come to our museum because his uncle had been killed in the Hoddle Street Massacre. I found this man leaning over the aerial photograph of the scene trying to work out where his family relative had died. I realised what he was trying to do, so I got out all the books and we worked it out. He was basically getting closure for his whole family who lived in England. It’s a difficult subject.

The only other family members that we’ve had issues with, we had a sister of one of the other police officers who had been murdered. She sat down and she had a little bit of a cry. But at the end she showed her son and said, ‘this is your uncle’. She was actually really proud. We always encourage these people - we always tell them ‘it’s your museum’ sort of thing. Give them ownership over it. Because as difficult as it is, as these subjects are, we really try to focus on the stories of the people and also the stories of the police investigating the crime.

Even with the Walsh Street one with that murder weapon and the cartridges, the cartridges are actually really significant in that case as well because those cartridges are what linked the police to the guys who did it. Similar cartridges had been left at a bank robbery, or something, so they were able to work out who did it. I find it amazing. I find it a very difficult subject sometimes, especially as a collections manager registering this kind of stuff.

Disclaimer and copyright notice

This is an edited transcript typed from an audio recording.

The National Museum of Australia cannot guarantee its complete accuracy. Some older pages on the Museum website contain images and terms now considered outdated and inappropriate. They are a reflection of the time when the material was created and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Museum.

© National Museum of Australia 2007–25. This transcript is copyright and is intended for your general use and information. You may download, display, print and reproduce it in unaltered form only for your personal, non-commercial use or for use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) all other rights are reserved.

Date published: 01 January 2018