Alison Wishart, National Museum of Australia, 27 March 2009

ALISON WISHART: Hello everyone. Adele would like me to convey her apologies that she can’t be here today. But she is coming to the Museum on 6 April to talk about Australia’s culinary heritage, so you can catch up with her then. Together we have been researching Flora Pell and the significance of her most popular publication: Our Cookery Book. There is not enough time today to give you a comprehensive account of how this innocuous little cookbook opens a window into several themes in Australian social history, but we hope to do this in a forthcoming paper.

I will briefly sketch a few of the historical themes this book reveals before discussing some of the dilemmas in exhibiting this cookbook in a way that communicates its significance.

Nigella Lawson has a predecessor: her name is Flora Pell. While she looks more like the type of cook who would smack your hands for licking the bowl than suggestively lick her fingers, don’t be deceived. Pell was a first-rate, published and celebrated chef. She travelled to the USA on a study and lecture tour of cookery schools in 1923; she had her own spot on Melbourne’s 3LO radio station for three years from 1925 to 1928; and she spoke to business, women’s and charity groups about cooking.

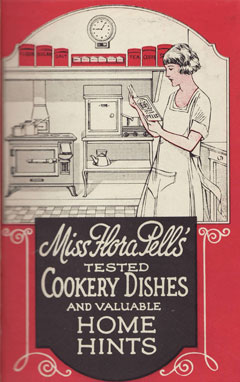

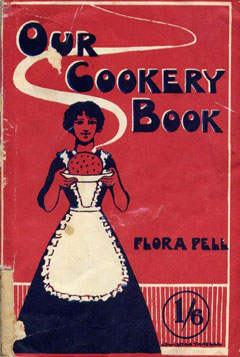

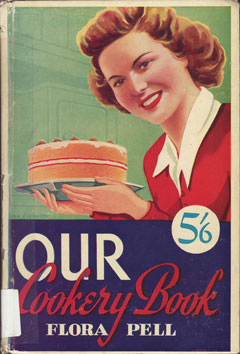

Her three cookbooks were highly regarded. The use of Pell’s name in the title of the third book [Miss Flora Pell’s Tested Cookery Dishes and Valuable Home Hints] implies that by the time this was published in 1925, Flora Pell was a household name. The most popular book, Our Cookery Book, was reprinted over 24 times from 1916 until the 1950s - beat that Nigella.

Our Cookery Book and the temperance movement

Our Cookery Book was used as an unofficial textbook in Victorian cookery classes from 1916 to 1929. When the Women’s Christian Temperance Union discovered in 1926 that school girls were using a cookbook that included half a cup of brandy in a fruit cake recipe, they lobbied the Education Department for two years and were successful in having all recipes with intoxicating liquor removed from subsequent editions. Our Cookery Book is an example of the power and persistence of the temperance movement in Australia in the 1920s.

Our Cookery Book and power

A close reading of Education Department files in the Victorian State Archives has revealed that Flora Pell was thoroughly ‘done over’ by the education bureaucracy in 1928 for daring to publish and promote her successful cookery book. Pell was twice called before the Director of Education to explain why her book was being used in schools and why she was collecting royalties. She eventually resigned after a 40-year career due to ‘ill health’ in 1929 at the age of 55.

Flora Pell defied social norms. She had a successful career and stepped outside the traditional role prescribed for women. She used her initiative to fill a gap in the cookbook and textbook market. I kept asking myself if a man with Pell’s talents would be treated this roughly by the department.

Our Cookery Book and the role of women in society

In terms of women’s role in society, Pell was a living contradiction. On the one hand she wrote and taught that a woman’s place was in the home and that it was her ‘heaven-appointed’ mission to be a wife and home-maker. On the other hand, Pell was a successful career woman who rose through the Education Department to be inspectress of all the domestic arts and cookery centres in Victoria. Ironically, she wrote in her 1914 report on the 62 centres under her guidance:

The decline in household skill and a weakening of maternal instincts ... are traceable results of the increasing employment of women outside their homes.

Perhaps Pell resolved this contradiction in her life by believing that if she didn’t marry and raise a family, then the next best thing she could do was to teach girls how to cook and run a household. She was an advocate of domestic feminism.

Our Cookery Book and the education of girls

Pell was passionate about her job. She firmly believed that a girl’s education was incomplete if she hadn’t been trained in the principles of ‘true household economy’ - cookery and nutrition. For Pell, girls were ‘guardians of the future’ and she saw a link between training girls to be wise mothers who ran efficient and effective households and the prevention of juvenile crime.

Pell was headmistress of the Collingwood Domestic Arts Centre for eight years and later inspectress of 12 domestic art centres and many cookery centres that mushroomed around Victoria. In these centres girls aged 12 to 14 years would come to learn about household management and cookery for two days a week, and then they would go to a normal high school for the other days. In this way Our Cookery Book can be seen to symbolise and reinforce socially conservative gender roles.

Our Cookery Book and patriotism

Through her cookbooks and her teaching, Pell espoused patriotism. She believed that nation-building starts in the kitchen and wrote in 1906:

The teaching of domestic economy is to be the power that makes the happy home, and the happy home means a prosperous nation, because, from the home, we must recruit our citizens.

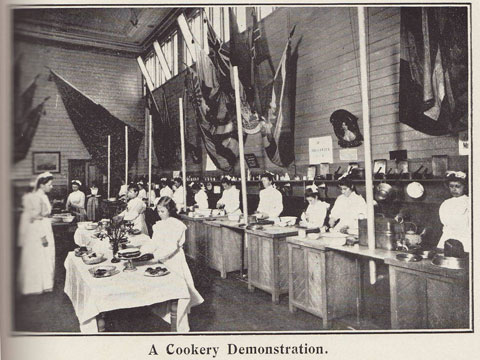

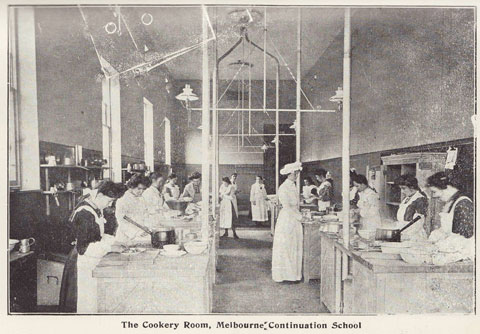

Here is a photograph of a cookery demonstration, organised by Pell, from the 1906 State Schools Exhibition.

Look carefully at the way the classroom is decorated.

And here is a photograph of a cookery classroom at the Melbourne Continuation School where Pell taught also from about 1906.

What do you notice about these photographs? Did you see the large flags draped from the walls?

Now I acknowledge that it was common to have a photograph of the reigning monarch on the classroom wall well into the 1980s, but I think these flags are noteworthy. These images sent me looking for photographs of science, maths and sloyd - which is what they called woodwork then - classrooms from that period, and none of them had flags festooned above the students’ heads. According to Pell, nation-building starts in the kitchen.

Our Cookery Book and nutrition

Our Cookery Book was first published in 1916 during the height of the First World War. With a rolling pin and a knowledge of nutrition, Flora Pell is teaching women to raise up an army. Pell was one of the first cookbook authors to talk about the importance of nutrition. In Our Cookery Book she stipulates the daily intake of foods which she calls ‘body-builders’, which we would call proteins; ‘heat-producers’, which we would call fats; ‘energy-producers’, carbohydrates; water and mineral salts. Today nutritionists would also say that vitamins and fibre are important, but these were not ‘discovered’ until the 1940s.

Adele Wessell and I commissioned a nutritionist from the University of Canberra to examine Pell’s recipes and compare what she recommended as the daily intake of protein, fat and carbohydrate with that recommended by the NHMRC, the National Health and Medical Research Council. She found that Pell’s recommendations are within the current standards recommended by the NHMRC. Interestingly, Pell’s recommendation of fat intake is at the lower end of the standard, even though her recipes mainly used saturated animal fats like dripping, suet and butter.

From an environmental point of view, Pell was probably ahead of her time in advocating and providing recipes for alternative source of protein to meat. She also encouraged cooks to use many different cuts of meat so that no part of animal was wasted. We would do well today to heed Pell’s advice about minimising food wastage and making economical use of cheaper cuts of meat and leftovers so as to leave a smaller food footprint on the planet.

Exhibiting and interpreting Our Cookery Book for a museum audience

One of the dilemmas for curators, as has already been pointed out in today’s symposium, is how to communicate the significance of objects like Our Cookery Book, which open a window into several historical themes. I have used about 1000 words to briefly discuss Pell’s publications, teaching career and philosophies about women, education, patriotism and nutrition. But in an exhibition context, a curator often only has 30 to 50 words to work with. Distilling the essence of an object and its multiple layers of meaning into so few words is extremely difficult, if not impossible. Nevertheless, here is my attempt to write a label for Our Cookery Book:

More than cake

Flora Pell was an expert cook. She wrote Our Cookery Book in 1916 which was used as an unofficial textbook in schools and reprinted in over 20 editions up until the 1950s. Your grandmothers may have learnt to cook from it.

However this cookbook was also controversial. The temperance movement forced the publishers to remove all recipes containing alcohol in 1928. The Victorian Education Department were annoyed that Miss Pell was reaping the royalties from sales of the book and removed this popular textbook from schools and replaced it with their own recipe cards.

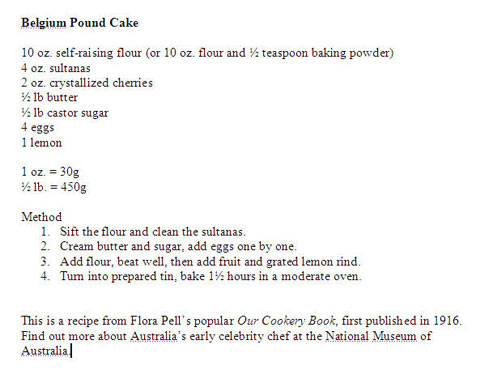

Want to taste one of the recipes?

Ask for a piece of Belgium Pound Cake at the Cuiseum café.

Of course it is unrealistic and unreasonable to expect one object to do all the interpretive work. There are other photographs and objects associated with Flora Pell, some of which I have shown you today, which could also be used.

Sometimes it helps to extend the interpretive toolkit beyond the object and the label. This is a recipe book. It’s about cooking and eating. As a visitor viewing this object, I would love to look at the recipes that it contains, but for the protection of the book it needs to be displayed behind glass. But given the recipes are no longer in copyright, it would be possible to reproduce some of them for visitors to take away, perhaps on attractive little postcards with a copy of the cover illustration on the front and a recipe on the back and some information about them [holds up samples of postcards].

When I was at State Library of New South Wales recently, that is exactly what they are doing to promote their cookbook collection - but I had the idea first. Recipes could also be printed on the NMA’s website. It would also be possible to ask the Museum’s café to cook some of Pell’s recipes like Belgium pound cake or lemon biscuits and make them available for sale to visitors. Hopefully the NMA’s café catering contract with the Hyatt is flexible enough to allow interpretation to extend beyond the galleries into other museum spaces. Being able to purchase a piece of Pell’s pound cake that was clearly labelled as such at the café would provide a tasty and memorable link for visitors to their experience in the exhibition gallery. It would also help to bring Our Cookery Book alive. I am interested to hear from other curators about ways to extend the interpretive tool-kit.

PETER STANLEY: Thank you very much, Alison. What a shame you didn’t think of Belgium pound cake for afternoon tea.

ALISON WISHART: Well, Peter, since you should mention that: I have cooked some Belgium pound cake and some lemon biscuits. If you get there quick enough, they will be available for afternoon tea.

PETER STANLEY: Save a slice for me. Of course, if I had known that, I would have given you time for questions.

Disclaimer and copyright notice

This is an edited transcript typed from an audio recording.

The National Museum of Australia cannot guarantee its complete accuracy. Some older pages on the Museum website contain images and terms now considered outdated and inappropriate. They are a reflection of the time when the material was created and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Museum.

© National Museum of Australia 2007–25. This transcript is copyright and is intended for your general use and information. You may download, display, print and reproduce it in unaltered form only for your personal, non-commercial use or for use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) all other rights are reserved.

Date published: 01 January 2018