Locating Ancestral Remains

How can a community find out where Ancestral Remains might be held? This is not always an easy process. Few institutions advertise what Ancestral Remains they hold. Many larger museums do have collections databases that can be searched online, but these are not always easily discoverable or up to date, nor do they always list all a museum’s holdings.

Within Australia, the best way to start is simply by asking state, territory and federal public museums and heritage agencies whether they have any Ancestral Remains or if they know where Ancestral Remains from a particular locality might be held. Most agencies will also be aware of other institutions where the collectors and donors represented in their own collections sent objects and Ancestral Remains.

Many museums have online databases of other Indigenous cultural material (non–Ancestral Remains). If the museum does hold materials from a community’s area of interest then it is worth approaching them to see if they have anything else that is not yet on their database. It is also useful to see who collected or donated the objects identified online. The collectors or donors may have a history of collecting and distributing Ancestral Remains, so when their names show up as donors of an object, there may be other items in the museum’s collections, including Ancestral Remains.

When it is not possible to get direct advice from an agency, a useful way to proceed is through a search of libraries and archives for historical documents from a particular region. This way potential collectors can be identified. The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), for example, maintains an excellent online library referencing system, where publications, manuscripts, newspaper articles and other media can be searched by location, group, author, personal name and so on. Their library thesaurus has search terms for ‘human Ancestral Remains’ and ‘repatriation’ that will show catalogue records for any materials that refer to those subjects. The documents can then be researched to see whether the writer made, or knew of, any collections of Ancestral Remains or other cultural material. It is, however, important to remember that no system is complete. There are always gaps, and new information is constantly being discovered.

The National Library of Australia has an extensive online search catalogue, including ‘Trove’, and is a recommended point for beginning searches. For example, a simple test search for ‘Aboriginal Skeletons’ in the search box turned up 1891 results, with identification of written works on Ancestral Remains from many localities in Australia and where those works are held. The AIATSIS library is linked to Trove. Other state and territory libraries also have online searchable catalogues.

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups have been identified by different names and spellings over the years. Minor variations in spellings, or the use of a variant term, can affect the results of a search. Different spellings and names should be tried. The AUSTLANG database at AIATSIS can be helpful as it shows many variant spellings for languages. Sometimes it will be more useful to search under ‘place’, or ‘subject’ rather than Indigenous community, nation or group.

All states and territories also hold official government archives. These archives can hold valuable unpublished information, especially relating to asylum and mental hospital records, prison records, colonial office papers, death records and people living on reserves.

The archives: missing Ancestral Remains, lost collections and museum exchange programs

Information available through online collections searches, or attached to the items or Ancestral Remains in the collections, is typically the tip of the iceberg, often just being a summary of the main historical attributes of the item — collector, donor, date and description, for example. Much more information may be held in the archives of the institution. This information could include the history and location of a collection, the name and residence of the donor, the circumstances of acquisition — whether by discovery, trade, purchase or donation — plus a note of other associated Ancestral Remains or people. Even collecting institutions can fail to do the deeper detective work into their archives when a request for information is received. It is important to try to follow up on every lead provided in the institution’s records.

Sometimes it will be necessary to research across institutions. Museums and other collecting institutions frequently exchanged Ancestral Remains as they tried to build up representative collections of ‘types’ of people, a practice now discredited. In such exchanges, the history of acquisition and the culture of origin was often considered irrelevant, and so minimal information was passed on. Similarly, a collector might not always have described the circumstances surrounding the removal of Ancestral Remains when donating or selling them to an institution. Some institutions, particularly anatomy departments in universities and natural science departments in museums, were only interested in such aspects as the biological characteristics of the Ancestral Remains: for example, signs of injury or disease. Cultural information was only used to identify local biological traits. The cultural history of the Ancestral Remains was irrelevant to them. Tracking the history of Ancestral Remains may therefore involve working with more than one institution.

What is provenance and why is it important?

‘Provenance’ refers both to the original source of an item and to its historical trail. The provenance of human Ancestral Remains encompasses the life of the living individual, the place and means of death and the location and cultural content of the burial. It then moves to include the history of the removal of the individual’s body or remains; the history of the donation, sale or transfer to a collector or collecting institution; the use of the Ancestral Remains by the collector or institution; the history of identification and requests for repatriation; the actual repatriation; and the subsequent management of the repatriated remains by the community into the future.

Sometimes information will be lacking and unrecoverable. For example, the name of the individual or of the associated funeral ceremonies will be unknown.

The major aspect of provenance for the purpose of repatriation is, however, determining place of origin. When the place of origin of Ancestral Remains is known, other aspects of provenance become easier to research. Ancestral Remains that have a provenance are thus typically first associated with a place. This allows for the identification of a cultural group affiliated with that place. In some instances, the name of the cultural group then allows an identification of place to be made. As noted earlier, traditional systems of change in land tenure may mean that living individuals may have limited or no biological connection with Ancestral Remains. However, they have the cultural, and often legal, rights to be recognised as the custodians of heritage and histories inherent in the lands that they now affiliate with and occupy. Place is important, as while populations and identities may fluctuate over time, the place of death or burial remains fixed.

The identification of place makes it possible to further refine research into historical documentation. It becomes possible to identify previous residents or explorers who may have taken Ancestral Remains, any other individuals and institutions these people may have been associated with and institutions or other organisations where their published and unpublished writings may be kept.

Sometimes research into provenance can reveal very detailed information, such as the name of the deceased individual and/or their place of interment. Sometimes provenance research can only reveal the region, or the state or territory, they were taken from. And sometimes it is not possible to unearth any information except that they come from ‘Australia’ — in such cases, these are known as ‘unprovenanced remains’. Even if no information is available at the time of initial investigation, this status of being unprovenanced may not be final. On a number of occasions, unprovenanced Ancestral Remains have been the subject of further research and their place or group of affiliation has been identified. This potential for the discovery of new information is important. It encourages wider research than sometimes happens in repatriation exercises. The designation of some Ancestral Remains as unprovenanced may simply be the result of poor or insufficient research undertaken at or by the returning institution.

What resources are available to establish provenance: compiling evidence

Resources useful for determining provenance are diverse and widespread; they range from oral testimony to a wide variety of written records or scientific testing procedures. They are available both locally and in all corners of the world.

The most valuable material is the historical record, which can be found in oral testimony, archives containing collectors’ journals, government records, museum collection records, newspapers, books and journals. Such archives sometimes even house the written or recorded experiences of living people with recollections of where Ancestral Remains were located, collected and subsequently stored, or who have worked with the cultural groups in the area of the Ancestral Remains. Land councils and heritage protection agencies have staff whose job it is, or has been, to identify, record and monitor sites of heritage significance, usually with the assistance of traditional owners and custodians. Asking these people whether they have any further information or relevant experiences can be a great help when it comes to establishing a provenance for Ancestral Remains.

Archival sources include libraries, state and territory archives, and institutional and museum records (see the Resources section at the end of this guide). It is important not to cease research simply at the most visible level of documentation. Ancestral Remains have been returned to Australia seemingly based only on the limited information stored with them; for example, with attached labels, storage boxes or the summary information in the collection register. Often more informative correspondence is held on older files not kept with the collections and rarely consulted by collection managers. Further research often locates more comprehensive documentation, leading to more precise provenancing. In general, experience has proven that more information can usually be located if the right research method is used.

As collections of human remains fell into disuse and were placed in store or transferred to other departments or institutions, so the danger of separation from their associated archives increased. This leads to a very common situation in which Ancestral Remains are divorced from their associated archive and very little is known about the archive, its location or even that it exists at all. Today’s museum curators are rarely fully acquainted with nineteenth-century archives and may not think that any exist. This is particularly the case with university collections, which rarely have specific curators, and there is much corporate memory loss. Sometimes information to locate an archive has been forthcoming from retired departmental staff, including technicians, and it is always worth talking with older members of staff to see what they may recall.

Provenancing research also relies heavily on cross-referencing people and events. Small snippets of information can be compiled to round out a full story of the history of Ancestral Remains. For example, in 1816 there was a massacre of Aboriginal people by British military forces near Appin in New South Wales. Although not explicitly stated in the official account of the time, several heads of victims were collected, including one of a named individual. The fate of these Ancestral Remains was unknown. However, in 1820 one head was mentioned in a book by Sir George Mackenzie called Illustrations of Phrenology. This book documented that the University of Edinburgh’s Anatomy Department had received the skull from a Royal Navy surgeon, who had earlier received it from one of the officers leading the massacre. The university numbered the skull of Carnimbeigle, the Aboriginal resistance leader, as ‘G10’. There were two more Ancestral Remains returned from Edinburgh at the same time. One is simply provenanced to the ‘Cow Pastures Tribe’ and identified as the skull of a female, similarly given to Mackenzie by Mr Hill. This is numbered ‘G11’. The third skull, identified as the ‘Skull of a Chief’, unprovenanced except to ‘New South Wales’ by the historical record, again has Mackenzie as donor. This skull was number ‘G9’. The similarities in collection history — the donors, the locations, the sequential numbering — provide strong circumstantial evidence that the two ‘unknown individuals’ were victims of the same massacre.

What this example presents is a sequence from known to unknown, or from the known to the lost, ranging from detailed historical records of an event, a named victim and the existence of their well-labelled Ancestral Remains (with clear-cut marks where the head was severed), to unmarked remains identified by accompanying limited information on location and donors, through to an originally anonymous, unmarked and largely unprovenanced skull. In these cases, quite basic historical research has been able to bring the hidden history to the surface and has identified two extra nameless victims, even if not by name.

Archival research

It may not be possible for everyone hoping to have Ancestral Remains returned to undertake the requisite archival research themselves. Such research requires access to records, which may be held in far distant locations and may be in different languages. It is worth asking institutions for copies of any information they may have. Research also often requires experience and knowledge of how to locate and work with archival record systems. Professional archivists, historians, anthropologists or other research experts can assist. This can be expensive, though many experts will provide what information they already have, or be willing to do the work, for free.

Ideally, an institution such as a public museum should do as much work as possible to research Ancestral Remains on behalf of a claimant group. It is part of their normal professional duties to answer public enquiries and to make information available to the public. While an organisation may ultimately refuse to repatriate Ancestral Remains, there is no reason why it should not pass on the historical information about the Ancestral Remains they hold; it can do this by either assisting in the research or providing community researchers with access to information, or both.

Within Australia, museums have acquired a body of expertise and knowledge through their repatriation experiences. The staff can often help, if not by doing the research themselves, then at least by providing recommendations and suggesting shortcuts to information they are aware of that could be relevant.

There are also a number of federal and state heritage agencies involved in repatriation. In some cases, these agencies have approached overseas institutions seeking the return of Ancestral Remains. When a government or representative agency takes on the authority and responsibility to make such approaches, it should also work to ensure that appropriate research is done into the provenance of Ancestral Remains. The agencies should encourage the holding institution to undertake thorough research into its files and documentation, or to allow access to appropriate researchers. However, there is a lot that can still be achieved independently using both online and local library references and books.

How did the removal of Ancestral Remains and their original shipment overseas occur, and what paper trail might this produce?

The motivations for removing Ancestral Remains were many and varied. Some were, and still are, simply collected as souvenirs. From the 1790s, in Europe, human remains began to be amassed from around the world for the purposes of studying human diversity, as understood through the now discredited notion of ‘race’. These European collections increased in size throughout the first half of the nineteenth century. By the mid-1800s the concept of evolution had become popular in science and human studies, and Ancestral Remains were collected as samples of physical ‘types’. Later studies began to consider that physical features on remains were also indicators of intelligence and cultural evolution, and Ancestral Remains of all cultures were collected and widely traded. This belief persisted until well into the twentieth century. The idea that Ancestral Remains were indicators of cultural development and intelligence has long since been discredited; nonetheless, the collections often still exist.

In Australia, museums began to amass collections of Indigenous Ancestral Remains from around the 1880s, and continued to do so sometimes until the 1980s, although the reasons for acquisition changed throughout this time. Some state museums still have the legal responsibility to store newly recovered remains until they can be returned to Country.

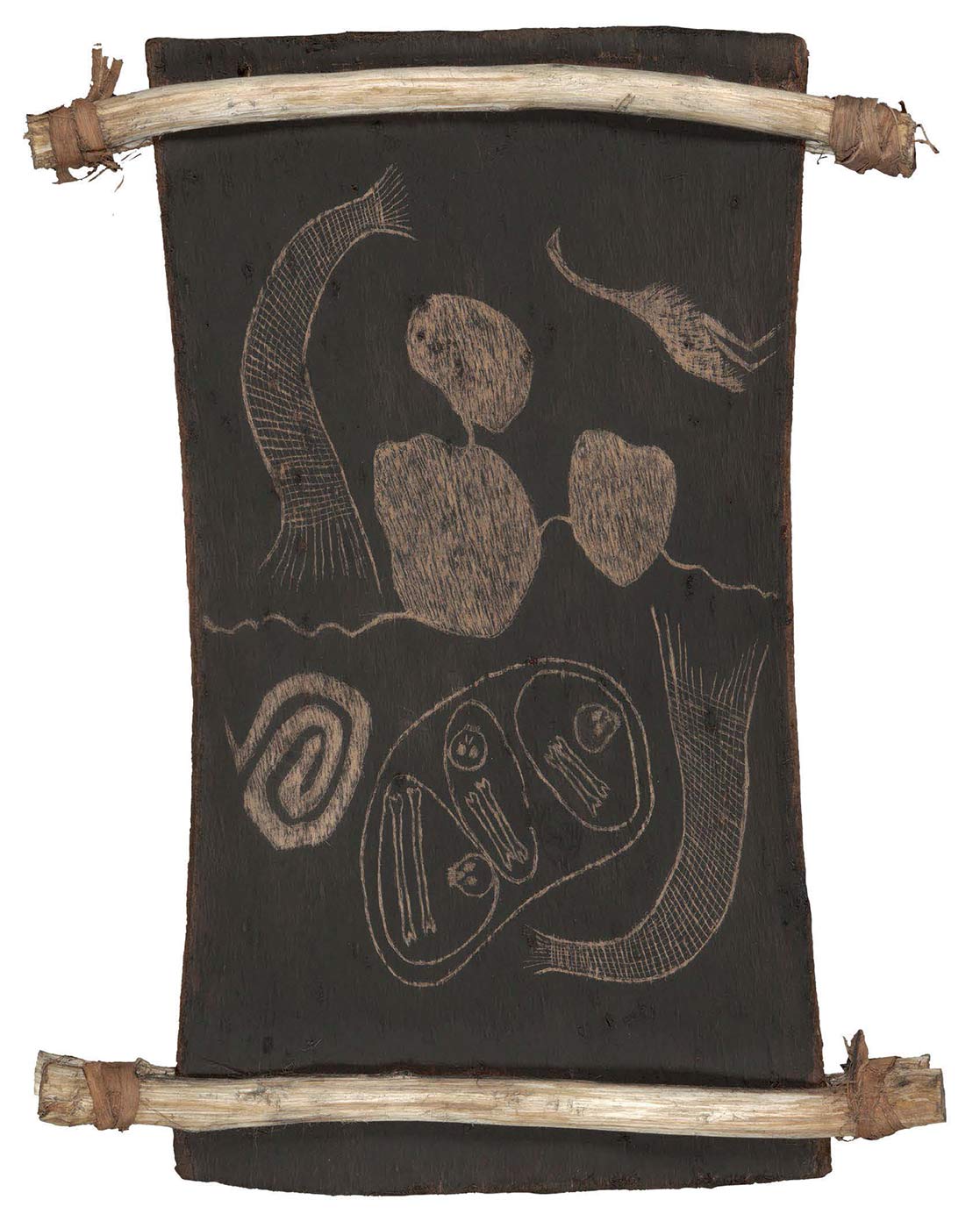

Ancestral Remains were also collected as objects of art. Where the Ancestral Remains were culturally modified — such as when they were painted with ceremonial designs, or where they had clay, shell, bone or wood attached — they are seen by museums as cultural artefacts. It is particularly difficult to persuade museums, and indeed private collectors, to part with these modified Ancestral Remains. Examples can still be found for sale as artworks by large and small auction houses and on online sales pages. Today the sale of Ancestral Remains in Australia is illegal, though it does occasionally occur. Trade persists overseas and online, in part because either laws prohibiting this trade don’t exist in all countries or, where such laws do exist, many people are unaware of, or deliberately disregard, them, but also often because of the items’ value as curios.

Most of the older collections of Ancestral Remains were made by people in the medical sciences for the purposes of comparative anatomical studies and for studies of racial differences. There was a particular focus on interesting pathologies that could be used to teach medical students about injury and disease. Examples showing cultural and non-cultural damage were sought: for example, tooth evulsion, where a tooth was knocked out during initiation; broken bones that had healed, either well or badly; diseases that affected the bone; tuberculosis; sexually transmitted diseases; dental decay and abscesses; wounds and similar damage. Such items were incorporated into teaching collections. Typically, the collectors of Ancestral Remains for medical specimens were unconcerned by the cultural context or attributes of Ancestral Remains, and much useful information important for establishing a provenance has been lost.

With the exception of phrenological (the study of skull shape) and racial studies, the targeted anthropological and archaeological collection of Ancestral Remains did not really gain momentum until the mid-nineteenth century. At that time there was growing interest in the study of foreign cultures, and Ancestral Remains were among the cultural ‘objects’ often collected, particularly when they had been modified. Such collections normally accompanied colonialism, and pressure was placed on people to part with Ancestral Remains. While most Ancestral Remains were stolen from graves and cultural repositories, some institutions argue that at least some of the Indigenous Ancestral Remains in their collections were legitimately acquired through direct sale or trade with, and with the free and informed consent of, the Indigenous seller. However, it must be acknowledged that the status of buyer and seller at the time was not equal. Indigenous custodians were often at a great disadvantage, either because they had no formal rights to prevent the sale or exchange or, alternatively, because they were needy to the point of starvation, thereby creating a situation in which the ‘sale’ or ‘trade’ of remains was the only way to survive. There is rarely any documentary proof that a free and informed trade and/or exchange actually occurred.

Even if a legitimate trade or sale did occur at the time, this does not disqualify today’s peoples from seeking the return of the Ancestral Remains.

Removal of remains by anthropologists and archeaologists

Anthropologists in Australia were acquiring Ancestral Remains from communities until well into the 1960s. And archaeologists were collecting them from excavations, with little regard for the opinions of local Aboriginal people, until well into the 1980s. By the 1990s, Australian archaeologists had recognised the rights of Aboriginal people to be consulted over archaeological work, including the discovery and treatment of Ancestral Remains.

Even though many archaeological and anthropological collections were acquired without Indigenous permission, they still have the advantage of being collected with a better process of documentation. (Site reports and professional publications provide much information.) This makes it far easier to return Ancestral Remains to their exact place of origin and, if required, to return them to their resting place in the same context and position as they were found.

Before the development of modern professional archaeological and anthropological recording and reporting obligations, some collections of Ancestral Remains were fairly well documented. Maps of locations of burial sites were made. Diaries describing the circumstances of the discovery, theft or purchase were kept. Details of the police engagement were also sometimes kept when the event in question was supported by law and committed by a judicial officer, not just a private atrocity committed by a private individual or mob. Newspapers would sometimes report on the death of individuals and the subsequent treatment of their Ancestral Remains. Documentation can include police reports, traveller’s diaries, correspondence between associates or donors and institutions, expedition accounts, museum catalogues and registers, receipts, unpublished or published reports, books, articles in professional journals and even the distribution of possessions in wills and estates.

Distributions, bias and the historical ages of Ancestral Remains

In arguments opposing repatriation, much is often made of the scientific importance of Ancestral Remains. While it is true that anything and everything has potential scientific importance, most collections are the result of long processes characterised by the destruction of evidence, and this severely compromises their value for science.

As we have seen, most of the larger Australian collections of Ancestral Remains were built up by anatomists, researchers into racial science or amateur collectors. In the process of collecting, whether by excavation of burials or by taking the bodies of the recently deceased, little regard was given to their cultural context. Ancestral Remains were stolen from graves, often without any documentation of how they were originally interred, what goods may have been associated with them, how deep they were, what soils they were buried in, how the Ancestral Remains were positioned in the grave, and so on. There was also the desire to procure ‘good specimens’, either strong and intact bones or ones exhibiting unusual pathologies. Bones prone to falling apart — either because they were very old and highly decayed, or because they were from young people and the bones had not yet fully formed — were often discarded. Often skulls were the only Ancestral Remains taken, with the rest of the body being left, discarded or destroyed. As a result, by the time the Ancestral Remains arrived in a collection their scientific value had been severely compromised. They were unrepresentative of either a biological or cultural population, either in time or in space. Rather they were biased towards the particular interests of the collectors.

The overall result is that many Ancestral Remains in older nineteenth- and twentieth-century collections are adult skulls, sometimes with an unusual pathology that can be seen in the bones or tissue, such as a healed or healing wound, a fatal injury, bacterial or viral bone infections, disease or dental problems such as abscesses. Alternatively, they will have features believed to show the racial characteristics the researcher had already decided they should have; for example, large teeth, thick eyebrow ridges or thicker bones interpreted as indicators of physical and mental primitivism. Few are likely to be any more than 500 years old, as the older Ancestral Remains are usually more fragile and break apart easily. Examining these collections, it would be easy to come to the conclusion that life was all hardship, injury and illness. However, it should be remembered that they were selectively collected and should not therefore be assumed to be representative of a population.

Archaeological evidence of mortuary practices

The development of greatly improved excavation and recording techniques in archaeology has gone some way towards ensuring that some cultural information has been preserved when Ancestral Remains have been excavated. Though even up to the 1980s, remains were often still excavated with little consideration of their importance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Archaeological evidence can now be of great value in reconstructing the cultural histories of Ancestral Remains, even when the items under consideration were not collected through archaeological methods. What archaeology has shown is that it is possible there were a variety of different interment practices within the same region. People were buried in extended burials, whereby the body was laid in the grave longways, or in bundle burials, whereby the body was tightly wrapped in a crouching position for burial. Cremation may have been practised. Secondary burials may have occurred, whereby the Ancestral Remains have been exposed somewhere to decay and then later wrapped in a bundle for burial or placement in a hollow tree or rock shelter. All these different forms of burial may have occurred in one and the same area over time. This is helpful when a group is seeking to determine what form of reburial may be appropriate.

Ethnographic evidence of mortuary practices

Ethnographic reports can be similarly useful. An ethnographic report is simply an observation of the practices of a cultural group written down by a researcher. Many settlers, scientists, collectors, missionaries, anthropologists and administrators recorded what they observed or were told. Sometimes these reports are inaccurate, but often they can help build up a picture of traditional mortuary practices, especially when there are several examples that can be compared for common features.

Old terms for language groups and clans

Names assigned to language groups and local clans often vary. As well as the name a group might call itself, there are names the group may have been given by their neighbours. There are incorrect spellings by non-Indigenous observers; there are mistakes where names of other phenomena are recorded as names of a group; some groups will be referred to by the European name of a location — for example, the ‘Cow Pasture Tribes’, the people who lived south of Sydney in the early 1800s.

This makes it important to look for alternative spellings. As mentioned earlier, a very useful resource is the AUSTLANG website maintained by AIATSIS. AUSTLANG allows for searches of language names, alternative and variant names and locations, as well as providing other resources.32

What about Ancestral Remains where archival information is poor or non-existent?

There are many Ancestral Remains that have no known associated information. They have either been collected without information about their location or cultural context having been recorded, or they have been passed on to others without including the original information. Sometimes a fragment of information may exist, such as a name of a collector or donor. It is possible to determine where those collectors/donors may have worked, though it may be difficult to narrow down a specific location or affiliated group. George Murray Black, for example, collected Ancestral Remains from along the Murray River region of Victoria and New South Wales in the 1920s and 1930s. While he often recorded the general locations from which he took crania, thus making them relatively easily to establish a provenance for, he often neglected to provide the same information on long bones (from arms and legs), which he also collected. We can make an educated guess that the large collection of unprovenanced Ancestral Remains Black is known to have collected came from one of the sites he excavated along the river, but cannot be sure as to which one, and thus cannot identify which specific groups should be consulted.

Most unprovenanced Ancestral Remains in Australian museum collections came from somewhere within the state or territory where that museum is situated. Ideally, those museums will also have an Indigenous Advisory Group that will have authority over the management of Ancestral Remains — at least until such time as the Ancestral Remains are returned to more appropriate custodians.

Who might these appropriate custodians be? Each repatriation event is a success in that it gets Ancestral Remains closer to home and increasingly under Indigenous authority. Even where Ancestral Remains are stored indefinitely, if they are under Indigenous control then their welfare is being safeguarded. That control might be exercised by a national, state, regional or local Indigenous agency with responsibilities for heritage issues within their regions. For example, in the Northern Territory, the land councils have elected boards, and each land council has a member of its board on the board of the Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority (AAPA), a territory agency responsible for the protection of sacred and significant sites. The AAPA Board is thus a progressively representative body for Northern Territory Aboriginal people. If the AAPA Board were to make a request for the return of Ancestral Remains provenanced only to the Northern Territory it is likely a museum would agree to that request. Where the provenance is better known, however, authorisation from the regional land council, local community, native title body or family would be required.

There is currently a debate as to what should happen to unprovenanced Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Ancestral Remains, those about which all that is known is that they come from Australia. The idea of a centralised Resting Place or Memorial in Canberra is being considered.33 There have been suggestions in the past that such Ancestral Remains might be reburied in one place, or cremated and spread across the country, or distributed to various state and territory Keeping Places. However, it should be recognised that access to historical records, as well as to non-destructive techniques for provenancing, will likely continue to improve over the years, with information and identification techniques becoming easier to access and apply, more accurate and more affordable. This will assist in provenancing remains that are currently unprovenanced. It is to be hoped that authority over the application and use of the information acquired through these methods will be in the control of Indigenous managers.

Scientific techniques

There are a number of scientific techniques that can assist in establishing the provenance of Ancestral Remains. Many of these are non-destructive, while others require interference and the possibility of physical damage. Some can be done by, or under the direct supervision of, the community. They should be used with caution, however, as none are 100 per cent accurate. They are best used to correlate and corroborate other sources of information.

The Repatriation Unit of the Australian Government Department of the Arts provides useful information on the risks associated with invasive/destructive scientific techniques.34

Revealing faded writing

Many Ancestral Remains were written on in ink or pencil at the time of collection. Typical information included the names of the collector or donor, the catalogue number or the name of the individual. These inscriptions can fade over time. Looking at Ancestral Remains under ultraviolet light or using infrared photographs can make faded or invisible writings visible. (NB Protective eyewear should always be worn when using ultraviolet or infrared lights.)

Metric analysis (craniometrics)

Metric analyses involve taking measurements of Ancestral Remains, and then comparing the measured characteristics with existing databases of Ancestral Remains. It is based on the premise that skull shape is related to ancestry, and thus can be used to identify what population that skull most closely ‘belongs’ to. However, much recent scholarship has questioned the ability of this technique to make such identifications. There are various issues associated with these techniques, and these should be understood before a choice is made to use them, or allow their use by others in the repatriation process. Perhaps the most important of these is the limited number of samples for cross-comparison. The techniques generally indicate what other collections of Ancestral Remains those Ancestral Remains under investigation look most similar to. However, there is no guarantee of direct biological or social linkage; it may just be an apparent one, based on physical similarities. For example, one Ancestral Remain was subjected to metrical analysis and provenanced to a specific group in south-eastern Australia. Subsequent independent research, undertaken by a researcher who was not aware of the metric provenancing work, discovered documentation that conclusively demonstrated the Ancestral Remains were from a named individual from northern Australia.

Non-metric analysis, which involves examining the anatomy and pathology of remains, also looks for particular traits that may be genetic. Usually, these are small features on the Ancestral Remains, such as a bump or crease in a bone that appears most frequently in one particular cultural group or population, or a characteristic of tooth development (such as ‘shovel-shaped’ incisors).35 Hair samples were similarly often collected, in the belief that hair colour, thickness, cross-section and curliness were indicators of biological affiliation.36

Isotopic analysis

Isotopic analyses involve analysing radioactive particles, minerals and chemicals in soils that may attach to Ancestral Remains (non-destructive) or, occasionally, get deposited in bones and teeth themselves (destructive). Samples are taken and analysed for their particular isotopic characteristics, then compared with the isotopic characteristics of certain places or foods found in certain places. While this testing is useful, the difficulty in Australia is that there are too few comparative samples. Parts of the landscape have different characteristics in their soil; a riverbank can differ from a swamp, which can differ from a hill or a desert. Even within local landscapes, there can be micro-environments. To provenance Ancestral Remains requires a match between the soil on the Ancestral Remains, or the Ancestral Remains themselves, and the soil at the suspected location. As can be imagined, this requires having thousands of samples for comparison. Isotopic analysis, therefore, has its best potential when other information has narrowed down the likely area of provenance. Even then, the collection and analyses of comparative samples is likely to be expensive.

Genetic (DNA) analysis

There are two common applications of genetic testing. The first is testing of modern samples, known as ‘DNA’ testing. The second is the testing of older Ancestral Remains, known as ‘ancient DNA’ testing or ‘aDNA’.

DNA testing is probably the best known application. It focuses on taking DNA samples from living people and/or the recently deceased. Its usefulness has been exaggerated by television and movie shows in which the rapid identification of DNA leads to immediate answers to questions of identity.

Ancient DNA testing is the analysis of the genetics of Ancestral Remains, though it is not as accurate as modern DNA testing, owing to the tendency of DNA material in old remains to degrade and become lost. However, it can be used to test whether two sets of Ancestral Remains are related or linked biologically.

There is no denying the potential usefulness of DNA and aDNA analysis for identifying affiliations between deceased and deceased, living and living or deceased and living peoples, but, as yet, there has been very little work to understand the full impact of its application in the area of repatriation. It is certainly not the magic solution that some people think.

Genetic testing can be used to link Ancestral Remains either to other Ancestral Remains or to living people, and to link living people to Ancestral Remains. However, just because results may not show a connection between a living person and an ancestor does not mean that a person is not related to that ancestor or to other ancestors in the culture at the time that ancestor was alive.

Genetic testing brings with it the potential for social damage. Such testing provides a biological genealogy at the expense of the social genealogy. Social genealogies provide historical perceptions of parentage and origins and also allow for non-genetic social processes such as adoption, inheritance, bestowal of rights and succession.

On occasion, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have inquired about having genetic testing of Ancestral Remains so that affiliation can be identified, often for the purpose of resolution of disputes over Indigenous identity, such as in land claims, native title claims and community membership. The people making such requests are often unaware that genetic testing requires not only the testing of the Ancestral Remains, but also the cooperative testing of community members.

There is always the possibility that the Ancestral Remains come from a migrant or guest, rather than from a long-term member of the historical landowning group. Research in land and native title claims has identified circumstances of birth or parentage that were unknown to the particular claimant and their community. Such discoveries may be historically and biologically accurate, but they can also conflict with historical cultural processes, belief of one’s own history and identity and a community’s belief in its own family structures. Genetic testing can aggravate this distress through extending biological differences back through a greater period of time than that covered by documentary or memory-based records.

The age of Ancestral Remains is also an issue. The older the Ancestral Remains the more widespread, and hence reduced, is the genetic trail. Assuming people have two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents and so on, by the time we go back 200 years we are looking only at who might be just a partial contributor to a person’s genes, in a situation where the other contributors are effectively invisible. Furthermore, not all genetic information is passed on, and some disappears through natural processes over time. Limited or lack of proof of genetic affiliation to one known set of Ancestral Remains does not, therefore, mean that a person does not have a stronger relationship to other people from the same area in the past whose remains may have not been discovered.

Caution should be taken when approaching commercial DNA testing companies. There are many commercial service providers available, with most based overseas. These service providers do not have any reliable or extensive databases on either modern or ancient Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander genetics. Their databases and methods are unsuited to the analysis of ancient DNA. Most of their public customers are Europeans. They will test individual samples against a larger European or Asian database and provide affiliation with the nearest match. It is possible that testing of Indigenous Ancestral Remains, or modern living Indigenous people, will align the tested individual with Asian or European ancestry before Indigenous Australian ancestry, simply because the testing laboratory does not have enough Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander genetic information on record.

Such testing will also be expensive; a 2017 price had standard over-the-counter testing at A$149 per sample. Specialised testing between community members is likely to cost more, as is extraction of DNA from the bones of a deceased ancestor. It also requires the willing participation of the community members — always remembering that such testing will not only show relationships between individuals and the Ancestral Remains, but also those between living individuals. Popular commercial DNA laboratory services may not be suitable for repatriation.

The ownership of genetic information is also an important consideration. Most service providers will retain information in line with their desire to expand their comparative databases. Some researchers who endorse genetic analyses of Ancestral Remains for repatriation purposes are known to retain the information for other research purposes. Before any approvals or permissions for genetic testing are given, it should be determined who will own and possess the information and who will have rights over its use in the future. Remains should be under community control before any DNA testing is undertaken.

There are increasing efforts to provide ethical genetic investigation services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people interested in genetic testing. A ‘National Centre for Indigenous Genomics’ is now housed at the Australian National University.37 The centre is overseen by the National Centre for Indigenous Genomics Governance Board, which has an Indigenous majority.