This chapter describes some strategies for the care and management of Ancestral Remains following repatriation. The act of repatriation by an institution should not be dependent upon a finalised outcome for the post-repatriation treatment of the Ancestral Remains. That is for the receiving community to decide, and there may be some time between the return and the final decision and action as to management. This period may involve storage of Ancestral Remains until reburial, or some other form of funerary treatment, is decided upon.

Community experiences of repatriation

As repatriation events have increased over the years, so too have community strategies for the management of Ancestral Remains. There has been concern over appropriate actions, as while all communities had a tradition of burial or other culturally appropriate disposal of Ancestral Remains, none had a cultural protocol specifically for Ancestral Remains that had been removed and then returned years later. For example, what ceremonies, if any, are most appropriate? Is a Christian ceremony appropriate for the Ancestral Remains of a pre-Christian individual? With some Ancestral Remains, such as those looted from graves, it could be presumed that, regardless of the later sacrilege of grave robbery, the initial burial was in accordance with cultural protocols and beliefs, and the spirit had, at least in part, been laid to rest. A future reburial or disposal may therefore be less complex in the forms of ceremonies that may be required. However, with others denied proper funerary ceremonies owing to their having been stolen immediately after death, such as those taken from medical institutions, massacre sites or those that had somehow been denied appropriate burial at the time of death, questions arise. For example, there can be concerns over whether the spirits still remain in the Ancestral Remains and over the type of ceremonies that would now be appropriate.

Over time, many communities have addressed these issues and have developed various strategies to receive, manage and rebury Ancestral Remains. Some are simple, but some are more complex. The main requirement is that they should satisfy the needs and beliefs of the community.

Groups new to repatriation can often feel confused about the appropriate actions to take. It can be a relief when they see what other communities have done. It is always worth contacting other groups that have received Ancestral Remains to discuss what their concerns were and how they dealt with the cultural issues. This provides options to consider, rather than imposing mandatory conditions. For example, some actions have included the simple reburial of Ancestral Remains in a safe place, aided by a few Elders and heavy machinery, burials in cemeteries and the housing of the Ancestral Remains in a dedicated Keeping Place. Ceremonies have ranged from private family groups through to inviting the local townspeople to attend and participate. Presiding dignitaries have ranged from just Elders through to representatives of the local churches and local, state and federal government agencies.

A museum, land council, heritage agency or other aid group should be able to provide contacts with other experienced communities.

Keeping Places prior to Final Resting Place

Once Ancestral Remains have been returned to a community, the question arises over where they should be held. Again, what is acceptable is the decision of the community. Ancestral Remains have been held in locked cupboards, filing cabinets and safes, or in Elders’ homes, large rooms and warehouses. The holding place is often subject to an appropriate cleansing ceremony.

The main attribute of Keeping Places is that they are all to be treated with respect, regardless of appearance. They are all characterised by having a dedicated function — that of protecting Ancestral Remains — with access restricted to appropriate people, such as community Elders. Keeping Places may be incorporated into a larger cultural facility, or they may be independent secure sites.

Security

The biggest issues for a Keeping Place are security, including protection from theft, fire, floods and vandalism, and pest management. Some repositories have been subjected to acts of vandalism and/or theft. Theft is usually opportunistic, with the person expecting to find boxes of valuables, rather than a deliberate attempt to steal Ancestral Remains. There have also been repositories, usually holding sacred objects, and in remote unsupervised locations, that have been destroyed or damaged by deliberately lit fires.

There are options for the safe storage of Ancestral Remains. For example, lockable rooms, safes, fire-rated filing cabinets or lockable insulated shipping containers situated in an observable area. Simple security systems are available. Using non-inflammable building materials and shelving, and having convenient fire extinguishers, lowers risk. The Ancestral Remains, and accompanying records, should also be raised off the floor, away from pests and from any seasonal flooding levels. To avoid individual distress for those uncomfortable with being in the immediate presence of Ancestral Remains, records should be kept in a separate room whenever possible, as well as copies with the remains themselves.

Occupational health and safety

The health and safety of people who work with or around Ancestral Remains is important. Most Ancestral Remains are physically harmless. However, there are risks. For example, storage conditions can create issues. High humidity can encourage the growth of mould, or the regrowth of old mould. Moulds, whether alive and dead, can provoke allergic reactions in susceptible people. Some Ancestral Remains were painted white using lead paint, to make them more impressive when on display. Lead is hazardous. Chemicals such as the insecticide DDT and arsenic were used to preserve Ancestral Remains and to control pest damage. Mercury was used to measure the size of internal sinuses, and traces can sometimes remain inside or on Ancestral Remains. Where an individual died of, or with, a disease, there is a remote possibility of some residual biological hazard. Tissue specimens were often preserved in formaldehyde, which is a dangerous chemical. Residues of chemicals can persist for some time and can impose a risk, although cases are rare.

To reduce risk, general handling of Ancestral Remains should be done using gloves, a filter mask and a dustcoat. Hands should be thoroughly washed after handling any Ancestral Remains or associated materials, including packaging. No food should be eaten or taken near Ancestral Remains. Ancestral Remains should always be handled in a well-ventilated space.

The repatriating museum or agency should have some knowledge of what risks may be associated with particular Ancestral Remains. They should be asked to comment on possible risks, and to suggest management options, prior to return.

There have been a number of published studies into the risks that Ancestral Remains may contain. Many of these are written for professional conservators or collection managers and may be hard to access and hard to read. Nonetheless, it is expected that the repatriating officer will be aware of what issues might exist and will advise the community accordingly.

Mental distress

An often-neglected area of health and safety risk is the possibility for mental distress. Not everyone is comfortable working with Ancestral Remains for extended periods. A conscientious worker will always appreciate that they are working with Ancestral Remains, and that the stories behind the collection of many of those remains are often tragic and distressing. There are also social and cultural values and beliefs for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous workers that may affect how they perceive Ancestral Remains.

No-one should be forced to come into physical contact with Ancestral Remains, even when repatriation is one of their duties. A person may be highly competent in advocacy, community liaison and skills relevant to repatriation, and yet be uncomfortable working with the Ancestral Remains themselves. This should be respected. Other people can be found who will assist with physical handling.

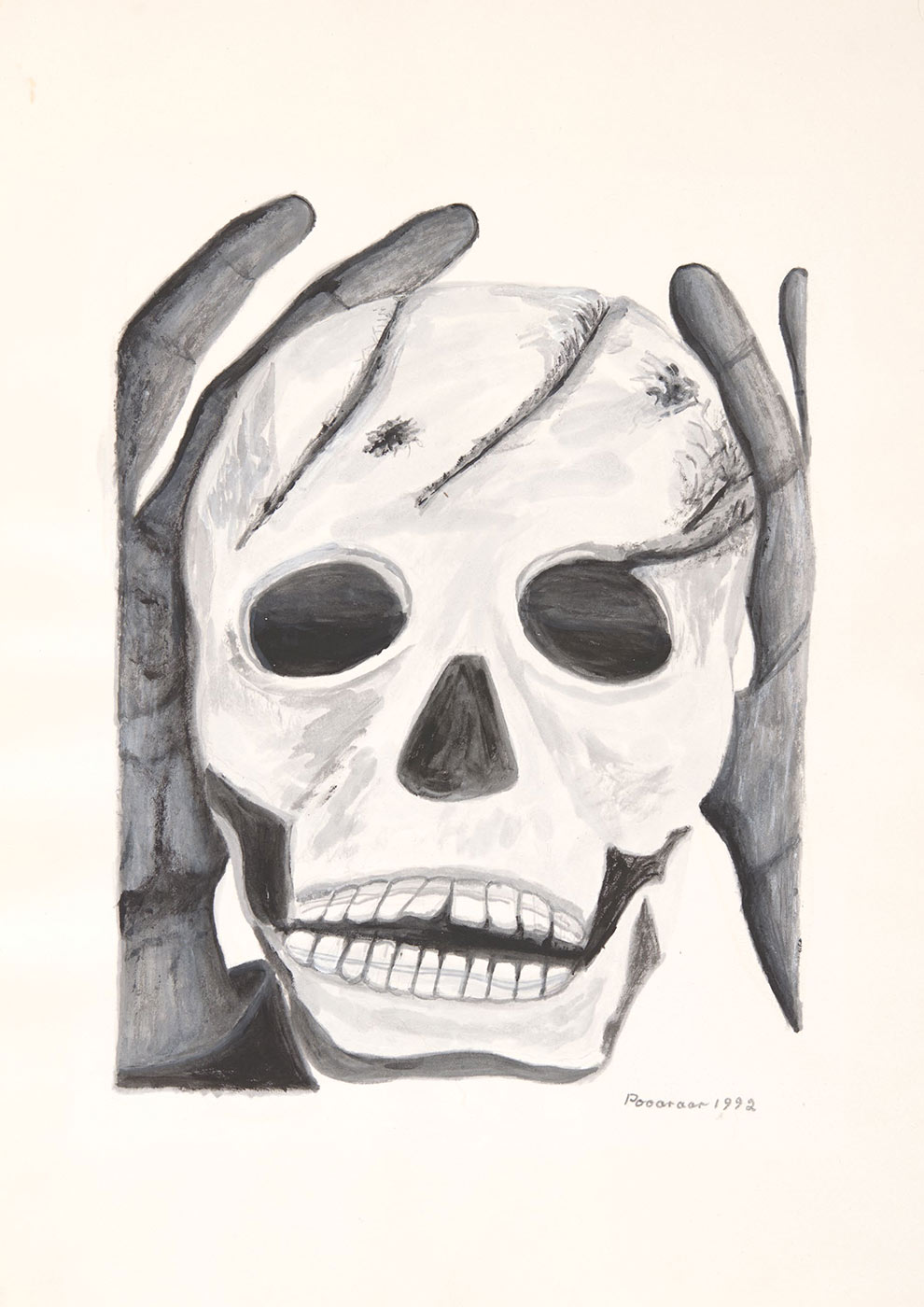

Caution should be exercised in getting younger people to work with Ancestral Remains. They have often been less exposed to death, and the first experience of it can be traumatic. It is difficult to backtrack when harm has already been done. There is also the risk that exposure may lead to the trivialisation of Ancestral Remains. (Skeletons and skulls are now popular decorative icons on clothing, and real or replica skulls can be bought from some stores.)

Any person likely to be working with Ancestral Remains should be thoroughly assessed for their willingness and/or suitability to do the work. They should be thoroughly briefed as to what the work entails and what sort of issues they may be required to confront. If a person wishes to withdraw at any stage of the repatriation process, they should be permitted to do so without judgement.

Pest management

Pests are a potential problem. Rodents can chew through boxes and Ancestral Remains. Insect pests can also destroy packing and organic material. Museum conservators can provide advice on the best form of cost-effective, non-hazardous pest management. Simple techniques include using bait stations, natural insect sprays and insect traps, but also monitoring collections before any infestations take hold.

Options for the Final Resting Place

As noted, many communities have little experience in the reburial of repatriated Ancestral Remains. There can be uncertainty about the most culturally appropriate form of reburial or interment ceremonies. Information about how other communities have responded to the return of Ancestral Remains can be provided by experienced museum repatriation staff, and through direct contact with other communities.

A museum officer may not be prepared to describe fully the process used by a particular community owing to requests for confidentiality. The officer should, however, be able to refer an inquiry to a community that can help directly.

The final management of Ancestral Remains must be determined by the community itself. Options applied by communities have included reburial, interment in burial vaults or in Keeping Places and other Final Resting Places, deposition in rock shelters and caves, and housing in Cultural Centres. In some areas where a tradition of display of Ancestral Remains has occurred, there have been discussions over whether a viewing-based Keeping Place might be appropriate, with access restricted to qualified community members.

The important thing is that no community should be pressured by external agencies to conform to a process of final management. Returns should be unconditional, and control over the process of final treatment of the Ancestral Remains is the right and responsibility of the recipient community.

Negotiation with landholders

Rules regarding access to lands for the purposes of reburial vary between states and territories. There are four main categories of land tenure in Australia: ‘Aboriginal Land’, ‘Crown Land’, ‘Leasehold Land’ and ‘Freehold Land’.

There are few difficulties in returning Ancestral Remains to places on Aboriginal Land. With land title invested in the community, it is the community’s decision as to where Ancestral Remains might be placed. Crown Land is typically nature reserves, national or state parks, waterways and stream corridors. It is usually administered by a government department that often includes heritage within its responsibilities. There have been a number of cases, in various states, where the assisting government heritage agency has been able to facilitate the provision of dedicated burial places for the respectful interment of Ancestral Remains.

Government Leasehold Lands are more problematic, and can range from suburban house lots in Canberra through to major pastoral stations in the Northern Territory. There are sometimes state and territory laws applying to Leasehold Lands that assign some rights of traditional practice, including burial, to affiliated Indigenous groups. This can help in arranging reburial. Those leases that cover vast areas are also less likely to be problematic when it comes to obtaining approval from the leaseholder, as the impact of a gravesite on landholdings and pastoral activities is insignificant, and no new rights are granted beyond those that already apply to the lease.

Nonetheless, it is always worth checking the legislation relevant to Leasehold Lands in the state or territory of concern. It is also important to engage with the leaseholder over any such activities. Locations of any reburials may have to be planned so as to not interfere with the leaseholders business operations.

Freehold Land is more difficult to access. Access to these lands will usually depend on gaining approval from the landowner. When the doctrine of native title was first recognised, there was a tendency for landowners to panic. This was largely a response to misinformation. The attitude that allowing Indigenous access to Freehold Lands will invoke land claims still persists. But it has been proven through the courts and legislation that this is not the case. Allowing people to rebury Ancestral Remains on the lands of origin is more of a courtesy than an extinguishment of Freehold Land rights and property title. It is worth being prepared to address issues of what rights are, and are not, bestowed should reburials occur on Freehold Land prior to engaging with the landowner. This information, complemented by courteous approaches, will greatly assist in solving any possible issues.

Reburying Ancestral Remains can bring a heritage site into existence. The site of the burial becomes a site of significance in accordance with Indigenous tradition. This can cause some conflict with non-Indigenous interests. It does not, however, constitute a loss of legal, proprietary title for those interests. If properly managed, the reburial will occur in a place that will not conflict with the landowner’s use, enjoyment or possession of the land.

Final Resting Place

A Final Resting Place can be a burial site or a safe store above or below ground. Regardless of whatever form the community decides the Final Resting Place will take, it still remains a grave, and hence it is entitled to the respect accorded to all graves. Reburial sites are, however, rarely marked. This is in accordance with Indigenous custom, as well as a means of preventing vandalism.

However, it is important that the location of all reburial sites should be recorded. This allows for the relocation of the site for ceremonial or respectful visits, and also assists in their future protection from disturbance through both legal acts, such as property development, and illegal acts, such as vandalism or other hazards, such as floods, erosion, stock damage or accidental disturbance.

Modern global positioning system (GPS) location equipment means that the location of a site can be recorded very accurately with little effort or training. This can be done by community members or by officers of heritage agencies. Most heritage agencies will, upon request, record sites as significant Aboriginal sites, though this should be the result of a decision of the community.

As well as GPS coordinates, there other ways to protect sites while ensuring their anonymity. One practice has been to lay heavy metal reinforcing wire over a burial site and then to bury the wire under topsoil. The site quickly becomes invisible as plants grow. The heavy wire prevents deliberate and accidental digging, as well as provides a significant metal signature detectable by metal detectors.

Regular monitoring is important, particularly in early years when knowledge of a reburial event may be widely known.

Usually, nothing prevents a community from marking reburial sites with other features, such as fences, grave-markers, memorial stones and plaques, and so on.

The role of ranger groups

Rangers drawn from communities provide excellent management and monitoring resources. As well as having been trained in heritage and environmental management, such officers usually have a strong interest in, and respect for, their own cultural heritage, and so work hard to ensure its protection.

Memorials

Memorials, such as plaques describing the repatriation event or the history of those interred, and gravestones are subject to the community’s choice. They can often be used to tell the story of a collection event and the subsequent repatriation, thus serving to educate visitors about the history of what happened. Memorials need not be located exactly at the site of a reburial. Memorial sites can also be places to which the actual location of the reburial site is linked. This information can be made known only to site managers, and the general public need not be aware of the exact location of Ancestral Remains in relation to the erected memorial.