The need to communicate clearly

Clear communication between all parties involved in repatriation is essential. Miscommunication, through lost correspondence, language differences, broken lines of communication or unfamiliarity with cultural protocols — both Indigenous and non-Indigenous — can lead to delays and mistaken beliefs. Patience is an important prerequisite in all communication.

Building relationships

The process of building a relationship with a collecting institution begins from the very first engagement. It is important that the philosophy of both claimant and institution be one of respect and trust from the outset, regardless of the outcome of the first repatriation attempt. It often takes a long time, sometimes several years, for repatriation consultations to have an outcome. Over this time, the claimant and the institution can learn from each other. A long-term relationship will ultimately facilitate future repatriations.

As noted previously, many institutions and curators, unfamiliar with Indigenous concerns, will often take an overly cautious stance in response to approaches for repatriation. Experience has shown, however, that direct and amicable engagements between claimants and institutions, engagements where knowledge is shared, can lead to a successful repatriation. As institutional representatives become more familiar with the claimant’s representatives, and as they learn more about the cultural and social backgrounds of the claimants and the Ancestral Remains, the more they are likely to become open to the concept of repatriation.

Similarly, institutions that collect cultural material need to appreciate the potential future benefits that may accrue from the relationships they are able to develop with Indigenous people. Experience has shown that consulting with the descendants of the makers can greatly enhance material culture collection information. Opportunities will also arise for new acquisitions. It needs to be remembered that today is tomorrow’s history, and that opportunities for the creation and collection of new knowledge should not be sacrificed.

Those museums that have engaged with Indigenous communities in repatriation activities have generally found that by so doing they have established a long-term friendship and opportunities for new knowledge and objects that they can present to their audiences.

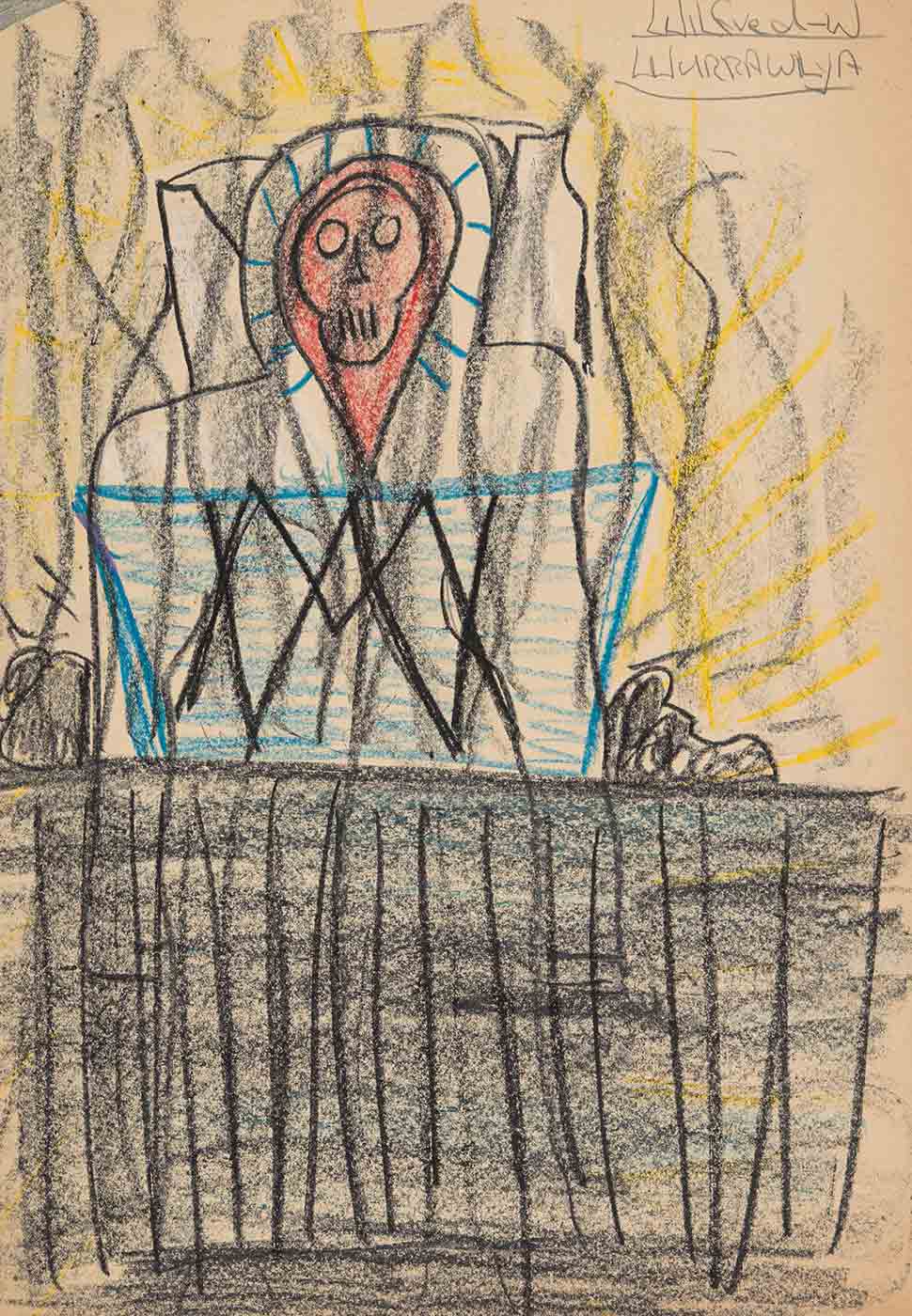

In 2004 Sweden returned a number of Aboriginal Ancestral Remains to communities in Australia. This followed meetings ‘on Country’ between the traditional custodians and representatives from Sweden. As an outcome, and an acknowledgement of this act of repatriation, in 2005 the King and Queen of Sweden visited Western Australia, where they were presented with gifts of artworks by the Western Australian Government. The Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture Centre also prepared a ‘Thank you’ DVD. The Swedish Museum of Ethnography now has an exhibition describing the history of the return.

Individual museum protocols

The protocols of each museum will vary according to its internal culture, its governance requirements, its previous experiences and the culture of the wider community it serves. It is important to be aware of how these may affect engagements.

All organisations develop an internal culture. Its philosophies, protocols, rules of behavior, and ways of dealing with inquiries evolve over the life of the organisation. By tradition, some will be conservative or progressive. Some background research into the previous responses by the institution to requests for repatriation is useful before meeting its representative. Similarly, a web search on the professional aspects of that representative will also help define likely attitudes and responses.42

Every institution will also have its own procedures of governance, even where a larger overlying code of governance applies, such as with larger government agencies. Internal governance is informed by the previous practices, and ideals, of that institution and may differ considerably from those of an unaffiliated, but otherwise similar, institution. Difficulties in dealing with one organisation may not occur when dealing with another owing to different internal governance procedures. A good knowledge of procedures that have worked in the past can be useful when engaging with different agencies, as it allows alternatives to be suggested.

Many institutions will also have some form of affiliation to professional groups, even if they have deliverables such as exhibitions or publications that are ultimately designed for a general public audience. Examples include health and medical museums, which will primarily affiliate with, and represent the interests of, people in the health and medical professions; social history museums, which will respond to historians; ethnographic museums, which will respond to anthropologists; and science museums, which are primarily concerned with technologists. Such museums will reflect the culture and ambitions of their professional interests. Again, the responses of various organisations can be expected to differ according to the professional codes of conduct of the people it employs.

Museum policy, national policy

All museums will also have their own policies. Some policies will be similar, some will be very different. Where the museum is funded by a federal, state or territory government, it can be expected that codes of conduct and governance applied across the public service will apply to those museums. In such cases, a museum’s internal policies must fit with the policies of its overseeing department and government. In some older institutions, particularly overseas ones, operating policies may have been established a long time before the current government took office, and they may still have flexibility in the development and implementation of their policies, in spite of the preferred current government governance guidelines. Alternatively, they may be more rigid, refusing to change their old policies and practices despite clear evidence of more progressive government policies and laws.

There are also a number of semi-autonomous and private organisations that have collections but do not rely on government funding, and hence are free from government or museum sector-imposed codes of behaviour. These organisations can develop policies to suit themselves. So long as the implementation of those policies does not break any relevant laws, then the institution is free to practise as it sees fit.

Recognising possible variations and differences in policy is important. It can be counter-productive to approach an institution and attempt to assert a government or industry policy position or legal requirement that is not applicable to it.

The role of Australian museums

The role of the major Australian museums is to work towards the repatriation of the Ancestral Remains in their care. This is asserted through the federal government, state government, industry representative bodies and individual institutional commitments. Museums can also provide advice on who to approach in other domestic and overseas institutions, as well as advice on how to prepare a repatriation claim.

While Australian museums are not officially endorsed by government to pursue overseas repatriation, they are not prohibited from doing so. In addition, museum staff will normally work informally to encourage repatriation when engaging with other institutions known to hold Ancestral Remains.

The role of Australian government agencies

There are a number of federal, state, territory and local agencies that can also assist communities to pursuing repatriation. Many of these are identified elsewhere in this handbook; they include the Repatriation Unit of the Australian Government’s Department of Communications and the Arts, state and territory museums, and state and territory heritage protection agencies. These organisations can offer assistance and advice. Perhaps most importantly, they can often provide an acknowledgement of status, a statement that a particular Indigenous agency is officially recognised under that state or territory’s heritage policies, laws or protocols and that it has a right, responsibility and authority to make representation for the return of Ancestral Remains. While nothing prevents any concerned person or group from making an application, evidence of government recognition and/or support can greatly facilitate the process.

Museum rights

Museums have a responsibility to return human Ancestral Remains, particularly where those Ancestral Remains have been acquired inappropriately, such as without free and informed consent, in violation of tradition or in breach of the law, among other reasons. However, museums also have corporate responsibilities to other charters, protocols and groups as well, not least to their audiences. An institution would be derelict in its duty if it did not consider how the activity serves the best interests of its wider client base. It is easy for repatriation advocates to see institutional delays in responding to requests as some sort of deliberate conspiracy. However, the obligation on the museum to practise ethical behaviour, based on considerations such as long-term, institutional and audience impacts, makes any museum’s decision to engage in a discussion about repatriation, let alone return Ancestral Remains, all the more significant.

A museum has a responsibility to its clients, the foremost of whom make up its audience. This includes the general public, other institutions, amateur and professional scholars, future users of the facilities and knowledge, sponsors, funding agencies, governments and special interest groups such as Indigenous communities.

Clearly, applicants for repatriation are important museum clients. Whether local or international, they are seeking the advice and assistance of an institution. Accordingly, the museum has a right to a degree of ‘self-interest’ in ensuring that its capacity to deliver ‘all things to all clients’ can readily be maintained. Therefore, a museum will invariably consider its repatriation activities in the light of what tangible and intangible benefits the activity brings — not only to the group receiving the Ancestral Remains, but also to other groups affected by their return.

It is, therefore, not unexpected that a museum might ask ‘How does repatriation benefit the museum?’, where by ‘the museum’ is meant not only the institution itself, but its local, national and international audiences, its clients, its contributors, the ethics of the industry and the obligation to advance both knowledge and society. What a museum is receiving in return is considerable: respect, admiration, new knowledge and, sometimes, new objects, new community engagements and community endorsement.