Irish bushrangers and beyond

The true story of the Irish in Australia would not be complete without a look at Ned Kelly and his gang of bushrangers. Kelly was well-known for his anti-British sentiment, something he shared with the Irish ‘rebels’ transported to the colonies years before.

The Irish were generally well-behaved when they arrived but several bushrangers had Irish roots, including Kelly and Martin Cash. The National Museum collection includes material relating to Kelly and bushrangers including Ben Hall, Frank Gardiner, Johnny Gilbert and Jimmy Governor.

The Kelly gang

Australia’s most famous bushranger is Ned Kelly.

Kelly’s mother, Ellen, was a free Irish immigrant. His father, ‘Red’, was born in County Tipperary, and transported from there in 1841.

Ned Kelly described Irish convicts as a ‘credit to Paddy’s land’, since they had died in chains rather than submit to English rule.

Edward ‘Ned’ Kelly was born in 1854. As a teenager he was in trouble with the police and took to stealing horses.

Feeling driven by police harassment, and the wrongful imprisonment of his mother on perjured police evidence, Kelly fled into the bush in mid-1878. Joined there by his brother, Dan, and 2 others, Joe Byrne and Steve Hart, they became the Kelly gang.

Outlawed

The gang was outlawed after killing 3 Irish-born Victorian policemen in 1878. For 2 years the gang robbed banks and evaded capture, largely because of sympathy for them among the struggling small farmers of north-east Victoria.

Kelly penned a detailed ‘manifesto’ of his grievances and tried to have it published. A transcription of Kelly’s Jerilderie letter is part of the National Museum collection.

The siege at Glenrowan

The Kelly gang was eventually cornered at the Glenrowan Inn. The police surrounded the pub, and a gun battle raged throughout the night of 27–28 June 1880. The gang had made suits of improvised armour to protect themselves. Each suit, made from the mould boards of ploughs, weighed about 44 kilograms.

Ned Kelly left the inn during the night, but returned next morning to help his friends. At first, his armour stopped the bullets, but he was brought down by wounds to his unprotected legs. Kelly’s refusal to surrender, and his loyalty to his mates when he could have escaped, has helped create the Kelly legend.

When he appeared from behind the Glenrowan Inn, Ned Kelly was a startling figure. Onlooker Thomas Carrington described a ghastly figure looking ‘for all the world like the ghost of Hamlet’s father with no head, only a very long, thick neck’. The initial failure of police gunfire to bring him down only added to the supernatural effect.

Kelly was eventually brought down by police sergeant Arthur Steele, who shot him in the legs. The National Museum holds the ceremonial sword later presented to Sergeant Steele by grateful pastoralists.

Verdict guilty, sentence death

Father Matthew Gibney, an Irish-born priest, rushed into the burning inn to see whether Steve Hart and Dan Kelly were still alive. He found them together, ‘two beardless boys’ lying dead in a back room, helmets removed. It is believed they shot each other.

When the siege of Glenrowan was over, the remains of Steve Hart and Dan Kelly lay side by side in a back room of the inn. Dan’s sisters, Maggie and Kate, who were at the scene, were said to have cried loudly and kissed his charred bones. Dan Kelly was 19 years old and Steve Hart was 21.

Byrne, a capable scholar at school, was considered the most literate member of the Kelly gang. Trapped in the Glenrowan Inn, he was raising his glass to toast the gang’s future when he was killed by a bullet that struck the main artery in his groin.

The Kelly story is one of the most written about in Australian history. By comparison, Kelly’s trial and death sentence, as recorded in the court book, took few words: ‘Verdict guilty, sentence death.'

Irish-born judge Sir Redmond Barry presided over Kelly’s trial. When Barry asked God to have mercy on his soul, Kelly replied, ‘I will see you there when I go.' Barry died on 23 November 1880, 12 days after Ned Kelly’s execution.

Installing the Kelly gang armour

The armour of the 4 Kelly gang members was on show for the first time outside of Victoria in the exhibition Not Just Ned.

David was part of the team which documented and mounted the 4 suits of armour. Each piece of armour weighed 10–20 kilograms.

Testing the Kelly gang armour

Many stories exist about the Kelly gang armour and people have long debated whether it was made at a blacksmith’s forge or in a camp fire. A detailed analysis of the armour which belonged to Joe Byrne found this suit’s manufacture was consistent with having been made over a bush fire.

A project by the National Museum of Australia, University of Canberra and the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation used neutron diffraction and x-ray technology to investigate the metal.

The report found the armour was made from good quality rolled steel, similar to that found in plough-shares. It also found the armour was fabricated under a low heat for several hours. The nature of the hammer blows and the degree to which cold-working occurred supported the notion that the armour was made by amateurs.

Read the full 2004 report, ‘Analyses of Joe Byrne’s armour'

- Download Analysis of Joe Byrne's armour449.1 kb pdf [ PDF | 449.1 kb ]

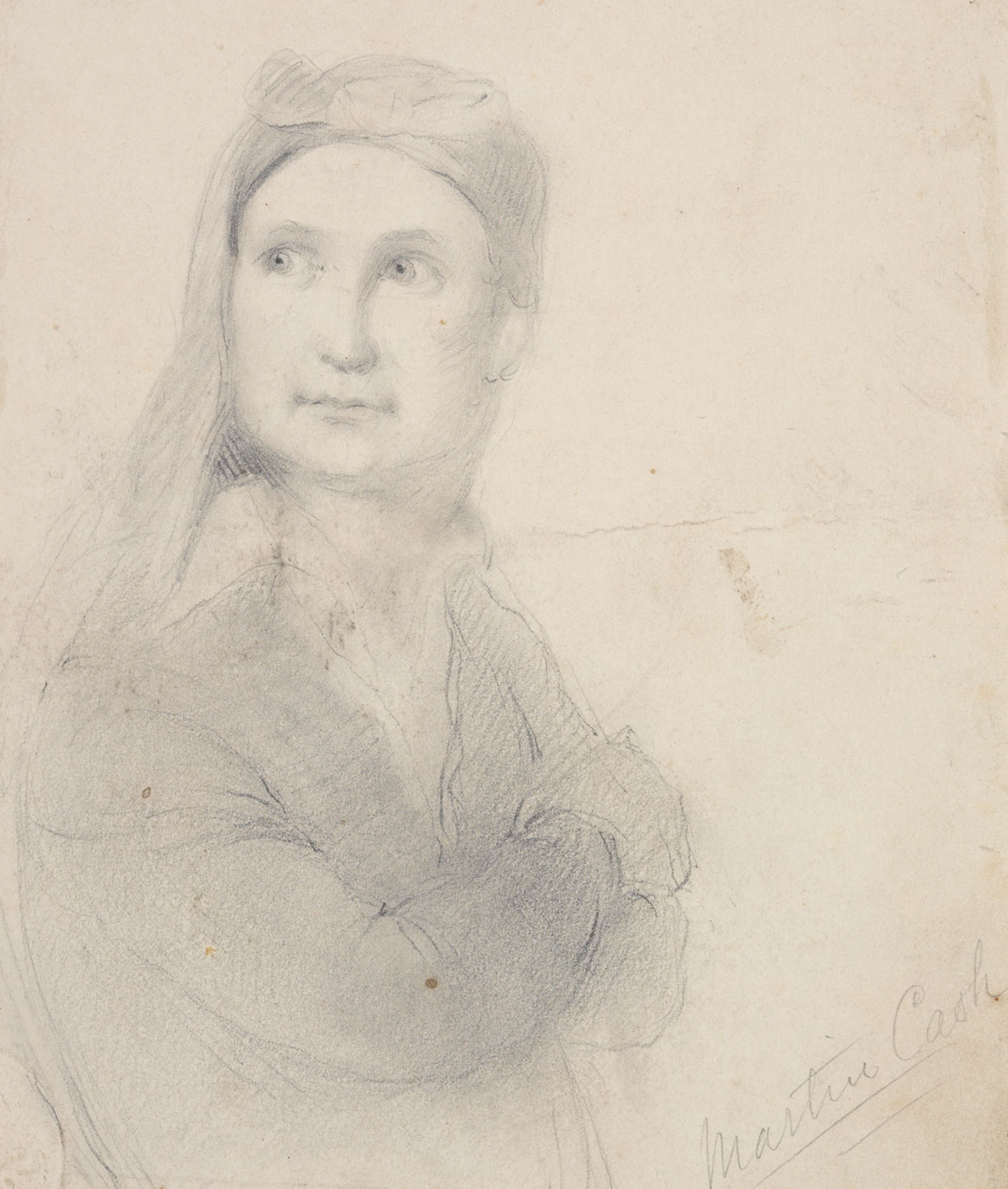

Gentleman bushranger Martin Cash

Martin Cash was one of Tasmania’s most notorious and popular bushrangers. Born in County Wexford, Ireland, Cash was convicted in 1827 of housebreaking. By his own account he shot at a man who was embracing his lover.

Transported for 7 years, Cash arrived in Sydney. There, he was convicted of further crimes and sentenced to seven years at Port Arthur.

Cash swam around Eaglehawk Neck with Lawrence Kavenagh and George Jones and became one of few men to escape from Port Arthur.

The trio robbed inns and the houses of well-to-do settlers without the use of unnecessary violence, earning them the reputation of ‘gentlemen bushrangers’. This was reinforced by Cash’s use of a walking stick which was actually a concealed weapon.

The men were recaptured after spending several months at large. Cash and Kavanagh were sent to Norfolk Island for life for murder. Jones was hanged in 1844.

After 10 years on Norfolk Island, Cash returned to Van Diemen’s Land a more subdued man. Towards the end of life, at his property in Glenorchy, Tasmania, his Irish charm and cheerfulness made him a popular scoundrel known to all.

Ben Hall, Frank Gardiner and the Lachlan bushrangers

Mobs of bushrangers led variously by Ben Hall and Frank Gardiner flourished in the Lachlan Valley region of central western New South Wales in the 1860s.

The bushrangers included John Gilbert, John O’Meally, Michael Burke, John Dunn, and others. Not all of these men were of Irish descent, but all lived in and ranged over remote and isolated country that had been settled in the 1840s and 50s, often by Irish immigrants and ex-convicts.

West of Bathurst, and south between Bathurst and Goulburn, the country was often poor. People ran cattle on small holdings for very little return. Resentful of authority, they often dodged on to the wrong side of the law.

The Walshes and the O’Meallys were typical of these Irish families. John Walsh had a cattle run near present-day Grenfell, and in the 1860s all his 4 children were caught up with bushrangers. Daughter Bridget Walsh married Ben Hall, and her sister Kate had a notorious affair with Frank Gardiner.

Over in the Weddin Mountains region, Patrick O’Meally ran cattle and maintained a sly grog shanty that was a meeting place for local law-breakers and tearaways.

The Goimbla raid

One of these law breakers was O’Meally’s son John, who joined Ben Hall for many hold-ups.

Gold had been discovered in the region in the early 1860s. It brought wealth and a new assertion of law and order.

Petty crime spiralled into major crime, and John O’Meally’s life came to a violent end when, with Gilbert and Hall, he attacked ‘Goimbla’, the homestead of David and Amelia Campbell, near Eugowra in November 1863.

In a 2-hour battle the gang set fire to the stable buildings, and O’Meally was shot and killed.

The National Museum collection includes an ornate coffee urn and sympathy letter presented to the Campbells in recognition of their courage, and in sympathy for the loss of their property.

Courageous resistance

In February 1865 Ben Hall’s gang also attacked the 4 Faithfull brothers of Springfield station, as they travelled into Goulburn.

To the surprise of the bushrangers the teenage boys fought back.

The National Museum’s Springfield collection includes an 1851 Colt revolver believed to have been dropped by one of the bushrangers.

Also in the collection are medals awarded to the Faithfull brothers by the New South Wales government in recognition of their courageous resistance.

The Museum also holds a pistol associated with Gardiner. It is believed he owned the weapon when arrested on a charge of horse-stealing in Yass in 1854.

Escort Rock hold-up

Gardiner later gained fame for leading a £14,000 hold-up on the Lachlan gold escort near Eugowra. A bullion box in the Museum’s collection shows how, after this hold up, bullion boxes were redesigned to be much stronger and more secure. Before that, Gardiner’s gang had easily been able to hack open the boxes they stole from the Lachlan escort.

Gardiner was tried and sentenced to 32 years’ hard labour for other crimes. In 1874 he was released by petition subject to exile. He left for Hong Kong and later lived in the United States, where unsubstantiated reports say he died in 1903.

Few of the other bushrangers lived lives as long as this. Michael Burke died in a raid on a homestead in 1863. Ben Hall was shot dead by police at Goobang Creek, near Forbes, on 5 May 1865. A few days later, Gilbert died in a similar way near Binalong. Dunn was apprehended by police and was hanged in March 1866.

You may also like